Then they nearly lost Lambert at the battle of Musselburgh, just south of Edinburgh, when his horse was shot dead under him and Lambert, falling, was lanced in the thigh. The Scots infantry spotted him, and a band of them were dragging him away from the battlefield when his own regiment, Yorkshiremen most of them, let out a yell of horror that made even the Highlanders check, and charged through the crowd to get to him.

The Scots pressed on southward for London; the English army chased after them until the Scots chose the ground and turned to face the pursuers outside Dunbar. The English were hopelessly outnumbered; injury, illness, and desertion had taken a dramatic toll. Cromwell was uncertain whether to go forward against the Scots or fall back. Only Lambert gritted his teeth and said they must fight then and there.

While Cromwell dropped the flap of his tent so that he might weep and pray in privacy, John Lambert mustered the army and told them simply and clearly that the Scots outnumbered them by two to one and thus they must fight with double bravery, double persistence and double faith. There were about twenty-two thousand Scotsmen drawn up for battle, and only eleven thousand of them. With the smile that Hester Tradescant secretly loved, Lambert pulled off his plumed hat and beamed at his troops. “I don’t think this is a difficulty,” he shouted. “Come on, Ironsides!”

Early in September, Alexander sent a one line note to John.

Scots defeated at Dunbar.

“Thank God,” Hester said piously when John held out the letter for her to read in the stable yard. She put her hand in her pocket and gave Alexander’s boy a coin.

“I already paid him,” John remarked.

Hester smiled. “I could give ten shillings for this news,” she said.

“Shall you tell Johnnie, or will I?”

She hesitated. “Where is he?”

“On the other side of the road, picking nuts from the horse chestnut trees.”

“You go,” she said. “It was your agreement with him that has kept him safe.”

“Praise God,” John said. “I have had some sleepless nights.”

He strolled around the house, savoring the warmth of the sun reflected from the walls, glancing up in passing at the flamboyant crest which his father had illegally composed and claimed. It didn’t matter now, John thought with satisfaction. There were so many newly created titles and such confusion about how titles had come into being, that they could claim to be baronets and no one would query it. Indeed, Johnnie might one day very well be Sir John Tradescant as his grandfather had always wanted. Who knew what this new world would bring? As long as the family could keep its place, could keep the business, could keep the plants; as long as the horse chestnut trees flowered each year and scattered down the precious nuts like a prodigal rain of wealth, as long as there was always a Tradescant heir to pick them up and set them deep in moist pots.

John walked across the little bridge that spanned the stream at the side of the road and then crossed to the acreage on the other side. He had planted a thick holly hedge as a windbreak and to shield the plant beds from curious passersby and he thought this year he might trim it to make it thicken out and to square off the top like a handsome green wall. He paused for a moment and looked upward. It would take more than a week of work to cut back the top boughs of the hedge and it would be a painful, awkward job. He smiled at the thought that at least Johnnie would be at home to help him, and then he opened the door set between brick lintels in the hedge and went into the garden.

It was part physic garden, part vegetable plot, a new sort of garden for a new age which prized science and medicine more highly than luxury and prettiness.

But from ingrained habit, John had made his herb and vegetable beds in a pattern like a knot garden, and they were strictly aligned to a central point where he had dug a deep hole, lined it with clay and filled it with water to use as a dipping pond for watering the garden. The beds nearest the pond were all planted with the rarer and more tender herbs that the College of Physicians had asked him to grow. He had planted the edges with lavender to keep insect pests away, and because lavender was a good paying crop, the flower heads could always be sold to the perfume-makers and the apothecaries. Farther away from the central pond radiated other geometrically shaped beds growing greens and brassicas, onions, peas, turnips, purple-flowered and white-flowered potatoes – the food crops of the country gardens which John was breeding and cross-breeding, trying to rid them of their tendency to blight, trying to find the largest and the most nutritious.

If ever they were visited by one of the more dour radicals or sectaries who complained of the riot of wealth and color in the rarities room or in the garden around the house, John would bring him over here and show how, in these beds, he was using his skills in the service of the people and of God.

Johnnie was at the far end of the garden where they had planted row upon row of saplings, ready for sale, and where they had a chestnut tree at each corner. White sheets were laid under the trees and Johnnie came every day at dawn and dusk to get the very best of the nuts before the squirrels ate them.

“Hey!” John called from the door to the garden. “Message from Alexander.”

Johnnie looked up and came through the garden at a run, his face ablaze with joy and hope. “The king’s reached York? I can go to him?”

John shook his head and mutely held out the note.

Johnnie took it, opened it, read it. John saw the energy and joy drain out of his son as if a leech of grief had suddenly fastened on his heart.

“Defeated,” he said, as if the word was meaningless. “Defeated at Dunbar. Where is Dunbar?”

“Scotland,” John said gruffly. “South of Edinburgh, I think.”

“The king?”

“As you see, he doesn’t say. But it’s over,” John said gently. “That was his last throw of the dice. He’ll go back to France, I suppose.”

His son looked up at him, his young face bewildered. “Over? D’you think he’ll never try again?”

“He can’t keep trying,” John exclaimed. “He can’t keep coming back and coming back and upsetting the country. He has to know that it was over for his father and it is over for him. Their time has gone. The English don’t want a king anymore.”

“You made me stay and wait,” Johnnie said with sudden sharp bitterness. “And I stayed and waited, like hundreds, perhaps thousands, of other men. And while I stayed and waited he didn’t have enough men. So he was defeated, while I stayed at home, waiting for your leave to go.”

John put his hand on Johnnie’s shoulder but the younger man shrugged it off and took a few steps away. “I betrayed him!” he cried out, his voice breaking. “I stayed at home obeying my father when I should have ridden out to obey my king.”

John hesitated, choosing his words with care. “I don’t think it was a close-run thing. I don’t think hundreds of men would have made a difference. Since Cromwell and Lambert have had command of the army they have rarely lost a battle. I don’t think your being there would have made a difference, Johnnie.”

Johnnie looked back at his father and his dark, beautiful young face was filled with reproach. “It would have made a difference to me,” he said with simple dignity.

He came into dinner in silence. In silence he went to bed. At breakfast the next morning his eyes were somber and there were dark shadows underneath them. The light had gone out of Johnnie once again.

Hester put her hand on his shoulder as she rose from the table to fetch some more small ale.

“Why don’t you go to Wimbledon today?” she asked him gently. “Your next crop of melons must be nearly ready to pick.”

“What should I do with the fruit?” he asked miserably.

Hester glanced toward John for help and saw the smallest shrug. “Why don’t you pack them up,” she suggested. “And send them to Charles Stuart in Edinburgh. Don’t put your name inside,” she stipulated cautiously. “But you could at least send them to him. Then you would know that you had served him as you should serve him. You’re not a soldier, Johnnie, you’re a gardener. You could send him the fruit you have grown for him. That’s how you serve him. That’s how your father served his father, and your grandfather served King James himself.”

Johnnie hesitated for only a moment then he looked to his father. “May I go?” he asked hopefully.

“Yes,” John said in relief. “Of course you can go. It’s a very good thing to do.”

Spring 1651

In the cold, dark days of February John was glad to go to London and stay with Frances, or with Philip Harding, or Paul Quigley, and join the men in their discussions. Sometimes one of the physicians would conduct an experiment and summon the gentlemen to watch so that they might comment on his findings. John attended an evening in which one of the alchemists attempted to fire a new glaze for porcelain.

“John should be the judge,” one of the gentlemen said. “You have some porcelain in your collection, haven’t you, John?”

“I have some china dishes,” John said. “They range in size from as big as a trencher to so small that a mouse could dine off it.”

“Very fine?” the man asked. “You can see light through them, can’t you?”

“Yes,” John said. “But strong. I’ve never seen the like in this country. I think we don’t have china clay which is fine enough.”

“It’s the glaze,” said another man.

“The heat of the furnace,” suggested another.

“Wait,” said the alchemist. “Wait until the furnace is cooled enough and you shall see it.”

“A drink while we wait?” someone suggested and the maidservant brought a bottle of Canary wine and glasses, and they drew up high stools to sit companionably around the alchemist’s working bench.

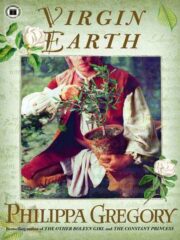

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.