The tide was coming in; the river, a mixture of salt and sweet, lapped at the sand beach. The girl was nothing more than a dark shadow against the dancing, gleaming water. J watched her blow on the glowing end of the twig and then put it to her cupped hand and blow again. She was lighting the herbs. J smelled a sharp, acrid smell like tobacco, carried to him on the onshore wind. Then he saw her scatter the smoking herb on the water.

She washed her face and her body, and then raised her wet head to where the moon was showing low on the horizon and lifted her hands in prayer. Then she turned back to the land and waded out of the water.

J thought of evening prayers at Lambeth, of his dead wife’s faith, and of the lodging-house woman who had assured him that these people were animals. He shook his head at the contradictions. He pulled off his boots and went into the shelter she had built them.

Inside she had heaped two beds of leaves. They were soft and aromatic. J’s clothes were neatly spread over the top of one heap, his traveling cloak on top of it all. J rolled himself up in its comforting smelly wool and was asleep before she had come inside.

J and the Indian girl stayed for nearly a month in the shelter she had built. Every day they went further afield, paddling in the morning in the canoe, and then she would run it aground and fish, or set snares for birds, while J foraged in the undergrowth for saplings and young spring growth. They would come companionably home in the light of the setting sun to the little camp and J would heel in his collection while she plucked the birds or cleaned the fish and prepared the evening meal.

There was a powerful dreamlike quality to the time. It was a relationship like no other. The grieving man and the silent girl worked together day after day with a bond that grew but needed no words. J was absorbed in one of the greatest pleasures a man can have – discovering a new country, a country completely unknown to him – and she, freed from the conventions and dangers of Jamestown, practiced her woodcraft skills and observed the laws of her own people for once without a critical white observer judging and condemning her every move, but only with a man who smiled at her kindly and let her teach him how to live under the trees.

They never exchanged words. J would talk to her, as he would talk to his little seedlings in the seed bed she had made for him, for the pleasure of hearing his own voice and for the sense of making a connection. Sometimes she would smile and nod or make a little grunt of affirmation or give a trill of laughter, but she never spoke words, not in her language nor his own, until J thought it must be as the magistrate had said and that she was dumb.

He wanted to encourage her to speak. He wanted to teach her English; he could not imagine how she could survive in Jamestown, comprehending only the outflung pointing arm or a clip to the head. He showed her a tree and said “pine,” he showed her a leaf and said “leaf,” but she would only smile and laugh and refuse to repeat what he told her.

“You must learn to speak English,” J said earnestly to her. “How will you manage if you cannot understand anything that is said to you?”

The girl shook her head and bent over her work. She was twisting supple green twigs into a mesh of some sort. As he watched she made the final knot and held it up to show him. J was so ignorant that he could not even tell what it was that she had made. She was smiling proudly.

She set the little contraption on the forest floor and stepped back a few paces. She dropped to her feet, hunched her back and sidled toward it, her arms stretched before her, her hands shaped like beaks, snapping together. At once she was a lobster, unmistakable.

J laughed. “Lobster!” he said. “Say ‘lobster’!”

She pushed back her hair where it fell over the left side of her face and shook her head in her refusal. She mimed eating, as if to say, “No. Eat lobster.”

J pointed to the trap. “You have made a lobster pot?”

She nodded and stowed it in the canoe ready for setting at dawn the next day when they went out.

“But you must learn to speak,” J persisted. “What will you do when I go back to England? If your mother is put in prison again?”

She shook her head, refusing to understand him, and then she took a twig from the fire and walked toward the river and J fell silent, respecting the ritual of casting tobacco on the water, which was the same at dawn and dusk, and which marked her transition from day to night to day again.

He went into the shelter and pretended to sleep so that she might come in and sleep beside him without any fear. It was a ritual he had developed of his own to keep them both safe from his growing fascination with her.

Only on the first night, when he had been so weary from paddling that he could not keep his eyes open, had he slept at once. All the other nights he had lain awake listening to her near-imperceptible breathing, enjoying the sense of her closeness beside him. He did not desire her as he might have desired a woman. It was a feeling more subtle and complicated than that. J felt as he might have done if some precious rare animal had chosen to trust him, had chosen to rest beside him. With all his heart he wanted neither to frighten nor disturb her, with all his heart he wanted to stretch out a hand and stroke that smooth, beautiful flank.

Physically, she was the most beautiful object he had ever seen. Not even his wife, Jane, had ever been naked before him; they had always made love in a tumble of clothes, generally in darkness. His children had been bound in their swaddling bands as tight as silkworms in a chrysalis from the moment of their birth, and dressed in tiny versions of adult clothing as soon as they were able to walk. J had never seen either of them naked, had never bathed them, had never dressed them. The play of light on bare skin was strange to J, and he found that when the girl was working near him he watched her, for the sheer pleasure of seeing her rounded limbs, the strength in her young body, the lovely line of her neck, the curve of her spine, the nestling mystery of her sex which he glimpsed below the little buckskin apron.

Of course he thought of touching her. The casual instruction from Mr. Joseph not to rape her was tantamount to admitting that he might do so. But J would not have hurt her, any more than he would have broken an eggshell in a drawer of the collection at Lambeth. She was a thing of such simple beauty that he wanted only to hold her, to caress her. He supposed that of all the things he might imagine with her, what he wanted to do most was to collect her, and take her back to Lambeth to the warm, sunlit rarities room where she would be the most beautiful object of them all.

J would have lost track of time in the woods, but one morning the girl started to take the thatch from the roof of the little hut and untie the saplings. They sprang back undamaged, only a slight bend in the trunks betraying the fact that they had been walls and roof joists.

“What are you doing?” J asked her.

In silence she pointed back the way they had come. It was time to go home.

“Already?”

She nodded and turned to J’s little bed of plants.

It was filled with heads and leaves of small plants. J’s satchel was bursting with gathered seed heads. With her hoeing stick she started to lift the plants, tenderly pulling at the thin filaments of roots and laying them in the dampened linen. J took his trowel and worked at the other end of the row. Carefully they packed them into the canoe.

The fire which she had faithfully kept glowing for all the days of their stay she now damped with water, and then scuffed over with sand. The cooking sticks which they had used as spits for fish, game birds, crabmeat and even the final feast of lobster she broke and cast into the river. The reeds which had thatched the walls and the leaves which had thatched the roof she scattered. In only a little while their campsite was destroyed, and a white man would have looked at the clearing and thought himself the first man there.

J found that he was not ready to leave. “I don’t want to go,” he said unwillingly. He looked into her serene uncomprehending face. “You know… I don’t want to go back to Jamestown, and I don’t want to go back to England.”

She looked at him, waiting for his next words. It was as if he were free to decide, and she would do whatever he wished.

J looked out over the river. Now and then the water stirred with the thick shoals of fish. Even in the short weeks that they had been living at the riverside he had seen more and more birds flying into the country from the south. He had a sense of the continent stretching forever to the south, unendingly to the north. Why should he turn his back on it and return to the dirty little town on the edge of the river, surrounded with felled trees, inhabited by people who struggled for everything, for life itself?

The girl did not prompt him. She hunkered down on the sand and looked out over the river, content to wait for his decision.

“Shall I stay?” J asked, secure in the knowledge that she could not understand his rapid speech, that he was raising no hopes. “Shall we build ourselves another shelter and spend our days going out and bringing in fine specimens of plants? I could send them home to my father, he could pay off our debts with them, and then he could send me enough money so that I could live here always. He could raise my children, and when they are grown they could join me. I need never go back to that house in London, never again sleep alone in that bed, in her bed. Never dream of her. Never go into church past her grave, never hear her name, never have to speak of her.”

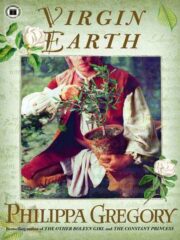

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.