She was arrested by the sound of a convulsive sob, and looked back in startled dismay to see that her aunt had burst into tears.

Mrs. Hendred did not like the people around her to be unhappy. Even the sight of a housemaid crying with the pain of the toothache made her feel low, for misery had no place in her comfortable existence; and when it obtruded itself on her notice it dimmed the warm sunshine in which she basked, and quite ruined her belief in a world where everyone was contented, and affluent, and cheerful. What she had seen in Venetia’s face overset her completely, and, since she had grown very fond of her niece, really pierced her to the heart. Her pretty features were crumpled: tears rolled down her cheeks; and she uttered in a sort of soft wail: “Oh, my dearest child, don’t, don’t look like that! I cannot bear to see you so wretched! Oh, Venetia, you must not take it so much to heart, indeed you must not! It makes me feel so dreadfully low, for I do most sincerely pity you, but it would not do—I assure you it would not!”

Venetia had started solicitously towards her, but at these words she checked, and stiffened. “What would not do?” she asked, keeping her eyes fixed on Mrs. Hendred’s face in a compelling way which set the final touch to the poor lady’s agitation.

“That man! Oh, don’t ask me! I didn’t mean— Only when I see you in such affliction how can I help but— Oh, my dear Venetia, I can’t endure that you should think I don’t feel for you, for I exactly enter into your sentiments! Oh dear, it brings it all back to me, but I promise you I haven’t thought of him for years, which just shows how soon you will forget, and be perfectly happy again!”

Very pale, Venetia said: “I don’t know how you should be aware of it—but what you have said I can’t have misunderstood! You are speaking of Damerel, aren’t you, ma’am?”

Mrs. Hendred’s tears flowed faster. She dabbed ineffectively at her eyes. “Oh, dear, I ought never— Your uncle would be so vexed!”

“Who told you, ma’am, that Damerel and I—had become acquainted?”

“Pray don’t ask me!” begged Mrs. Hendred. “I should not have mentioned it—your uncle particularly charged me—oh, I believe I am going to have one of my spasms!”

“If my uncle charged you not to speak, of course I won’t press you to do so, but will apply to him instead,” said Venetia. “I am glad I’ve learnt of this in time to see him before he sets out for Berkshire. I believe he has not yet left the house. Excuse me, aunt! I must go at once to find him, or it will be too late!”

“Venetia, no!” almost shrieked her aunt. “I implore you—besides, it wouldn’t be any use, and everything is so uncomfortable when he is displeased! Venetia, it was Lady Denny, but promise me you won’t say a word to your uncle!”

“If you’ll be frank with me, there is no reason that I know of why I should. Don’t cry! Lady Denny! Yes, I see. Did she write to you?”

“Yes, though I never met her in my life, for I was married before Sir John, but it was a very proper letter, and showed her to be a woman of excellent feeling, your uncle said. Though it was very disturbing, and upset me so much that I could scarcely swallow a mouthful of food all that day for thinking about it. For, you know, my dear, Damerel—!Not that you could possibly know, poor child, and I am not in the least surprised you should have fallen in love with him, because he is fatally attractive, though I am not, of course, acquainted with him! Still, one sees him at parties, and in the park, and at the opera, and— Well, my dear, scores of females— But to think of marrying him—! Which your uncle said was in the highest degree improbable—that such a notion should cross his mind, I mean! Only what to do I didn’t know, because your uncle thought it useless to invite you to come to town, and your being of age made it so very difficult, besides that he was persuaded your principles were too high to allow of your—your accepting a carte blanche, as they say!”

“None was offered me!” Venetia said, standing very straight and still in the middle of the room.

“No, my love, I know, but although it seems a dreadful thing to say, to have married him would have been worse! At least, I don’t precisely mean—”

“Don’t distress yourself, ma’am! Lady Denny was mistaken. Lord Damerel’s affections—were not so deeply engaged as she supposed. There was nothing more between us than—a little flirtation. He made me no offer—of any kind!”

“Oh, my poor, poor child, don’t!” cried Mrs. Hendred. “No wonder you should be so wretched! There is nothing somortifying as to fall in love with someone who does not share one’s sentiments, but that pain you need not be made to suffer, whatever your uncle says, for gentlemen don’t understand anything, however wise they may be, and even he owned to me that he had been mistaken in Lord Damerel, so he may just as easily be mistaken in you!”

“Mistaken in Lord Damerel?” Venetia interrupted. “Then—Aunt, are you telling me that my uncle saw Damerel when he came to Undershaw?”

“Well, my love, he—he thought it his duty, when you have no father to protect you! He considered it most carefully, not at first perceiving how he might be able— But then you wrote me the news of Conway’s marriage, and it was the most providential thing that ever happened, though I was never more shocked in my life, for it furnished your uncle with an excellent excuse to remove you from Undershaw, which he saw in a flash, because he is very clever, as I daresay anyone would tell you.”

“Good God!” Venetia said blankly. She pressed a hand to her brow. “But if he saw him— Yes, it must have been before he reached Undershaw—before I saw— Aunt, what passed between them? You must tell me, if you please! If you will not I shall ask my uncle, and if he will not I’ll ask Damerel himself!”

“Venetia, don’t talk in that dreadful way! Your uncle was most agreeably surprised, I promise you! You must not think that they quarrelled, or that there was the least unpleasantness! Indeed, your uncle told me that he felt most sincerely for Lord Damerel, and in general, you know, he never does so. He even said to me that it was a great pity that it should be out of the question—the marriage, I mean—because he was bound to acknowledge that he might have been the very— But it is out of the question, my dear, and so Lord Damerel himself acknowledged. Your uncle says that nothing could have done him greater credit than the open way he spoke, even saying that he had done very ill in not going away from Yorkshire, which your uncle had not accused him of, though of course it is perfectly true. Your uncle was not obliged even to point out to him, which he had expected would have been the case, and a very disagreeable task it would have been, and I’m sure I don’t know how—but that doesn’t signify, because Lord Damerel said that he knew well that it would be infamous to take advantage of you, when you knew nothing about the world, and had never been beyond Yorkshire, or met any other men—well, only Mr. Yardley!—so that you were almost bound to have fallen in love with him, and how could you understand what it would mean to be married to a man of his reputation? And you don’t understand, dear child, but indeed, indeed it would be ruinous!” She paused, largely for want of breath, and was relieved to see that the colour was back in Venetia’s cheeks, and that her eyes were full of light. She heaved a thankful sigh, and said: “I knew you would not feel so badly if you didn’t think yourself slighted! How glad I am that I’ve told you! For you are not so unhappy now, are you, my love?”

“Unhappy?” Venetia repeated. “Oh, no, no! Not unhappy! If I had only known—! But I did know! I did!”

Mrs. Hendred did not quite understand what was meant by that, nor did she greatly care. All that signified was that the haunted look which made her so uncomfortable had vanished from Venetia’s eyes. She gave a final wipe to her own, and beamed upon her suddenly radiant niece, saying with satisfaction: “One thing you may plume yourself on, though, of course, it will not do to say so, for that would not be at all becoming. But to have captivated such a man as Damerel into actually wishing to offer for you is a triumph indeed! For he must have meant to reform his way of life, you know! There was never anything like it, and I don’t scruple to own to you, my love, that if it had been one of my daughters I should be as proud as a peacock—not that I mean to say I think any of them could, though I fancy Marianne may grow to be a very handsome girl—and, of course, I should never dream of letting him come in their way!”

Venetia, who had been paying no attention, exclaimed: “The wretch! The idiotish wretch! How could he think I should care a jot for such nonsense? Oh, how angry I am with the pair of them! How dared they make me so unhappy? Behaving as though I were seventeen, and a stupid little innocent! My dear aunt—my dear, dear aunt, thank you!”

Mrs. Hendred, emerging from an impulsive embrace, and instinctively putting up a hand to straighten her cap, began to be uneasy again, for not even her optimism could ascribe the joy throbbing in Venetia’s voice to mere pride of conquest. “Yes, dear child, but you are not thinking—I mean, it cannot alter anything! Such a marriage would utterly ruin you!”

Venetia looked down at her in a little amusement. “Would it indeed? Well, ma’am, when Damerel came north it was to escape the efforts of his aunts to marry him to a lady of respectable birth and fortune, so that he might become reestablished in the eyes of the world. I don’t see how that was to be achieved if marriage to him meant her social ruin, and I can’t believe that the plot was being hatched without the knowledge and approval of Miss Ubley’s parents!”

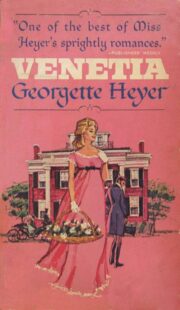

"Venetia" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Venetia". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Venetia" друзьям в соцсетях.