“Poor Clara! If only she could bring herself to see how very well out of a bad bargain she is!”

He said gravely: “I fancy she does in part realize that she was mistaken in Conway, but it is too soon yet for her to derive consolation from the knowledge that he is unworthy. I am sincerely sorry for her: the consciousness of her own fault weighs very heavily on her spirits, but she behaves with great dignity and courage. I had some conversation with her, and trust I may have given her thoughts a more cheerful direction. The subject is not mentioned at Ebbersley, and that circumstance, you know, has deprived her of the benefit of such rational reflections on the affair as one would have supposed Sir John would have introduced to her mind.”

“I am glad you were kind to her,” Venetia said, her lip quivering involuntarily. “But tell me how it is at Undershaw! Do they go on fairly well? I don’t mean Charlotte and Mrs. Scorrier, but our people!”

“Tolerably well, I think, but it was not to be expected that your people would be well-disposed towards Lady Lanyon when her coming meant your departure. From what Powick said to me, a se’ennight ago, they guess how it is, and resent it. You may be sure I said nothing to Powick to encourage such notions, but I could not but reflect, as I rode away from him, how much to blame—though unwittingly— I am for the awkwardness of the business.”

“You?” she exclaimed. “My dear Edward, what can you mean? Only one person is blameworthy, and that is Conway! You had nothing to do with it!”

“I had nothing to do with Conway’s marriage, nor could I have prevented it: that was not my meaning. But his conduct has shown me that the scruples which forbade me to urge you to consent to our marriage, after Sir Francis’s death, have resulted in an unfortunate situation which, had you been already established at Netherfold, would not have arisen. The present arrangement is on all counts to be lamented. I say nothing of the undesirable gossip it must give rise to—for although Aubrey might naturally have come with you to London, it cannot be thought natural that he should have chosen rather to remove no more than a few miles from Undershaw—but while he is within reach, and, indeed, frequently sees Powick, and your keeper, your people won’t render allegiance to Conway’s wife. I cannot think that right, and I suspect, moreover, that they are falling into the way of applying to him in any little difficulty.”

“I wonder what advice he gives them?” she said. “One never knows with Aubrey! He might give very good advice— if he happened to be in an amiable mood!”

“He should not give any. And however much cause he has to feel obliged to Lord Damerel he ought not to be living under his roof. I do not deny his lordship’s good-nature, but his influence I must think most undesirable, particularly for Aubrey. He is a man of few morals, and the tone of his mind must render him a most unfit companion for a lad of Aubrey’s age and disposition.”

It was a struggle to suppress the indignation which surged up in her, but she managed to say with tolerable composure: “You are mistaken if you imagine that Aubrey stands in danger of being corrupted by his association with Damerel. Damerel would no more dream of such a thing than you would yourself, even if it were possible, which I very much doubt! Aubrey is not easily influenced!”

His smile was one of conscious superiority. He said: “I am afraid that is a subject on which you must allow me to be a better judge than you, Venetia. We won’t argue about it, however—indeed, I should be sorry to engage in any sort of discussion with you on a matter that is not only beyond the female comprehension, but which one could not wish to see within it!”

“Then you were ill-advised to mention it!”

He returned no other answer than a slightly ironical bow, and immediately began to talk of something else. She was thankful that her aunt just then came back into the room, affording her a chance to escape, which she instantly seized, saying that she had a letter she must finish writing before dinner, and must therefore bid her visitor goodbye.

For how long he meant to remain in London she had been unable to discover, but from the evasive nature of his reply to that question she feared he contemplated a visit of indefinite duration. How to bear his company with patience, or how to convince him that his was a sleeveless errand, were problems not made easier to solve by Mrs. Hendred’s well-meaning efforts to further his suit.

Venetia soon discovered that during the period he had spent alone with her aunt he had made an excellent impression on her. In her view he was the stuff of which good husbands were made, for he was kind, dependable, of reasonable consequence, and comfortably circumstanced. He had succeeded in persuading her to the belief that his tardiness in bringing Venetia to the point was due to no lack of ardour, but to the nicety of his principles. Mrs. Hendred, herself a high stickler, perfectly understood his patience, and honoured him for it. He rapidly became established in her mind as a figure of unselfish devotion, and she thought it all very noble and touching, and spared no pains to bring this Jacob’s labours to a happy conclusion. She promoted his plans for Venetia’s entertainment and instruction, included him in her own schemes, and invited him so many times to take what she inaccurately called his pot-luck in Cavendish Square that Venetia was forced to protest, and to disclose that so far from having abandoned her intention of setting up her own establishment she was the more confirmed in it, and had inspected a house in Hans Town which she thought might be made into a comfortable home for herself and Aubrey.

She had not meant to make this announcement, which she knew would meet with much opposition, until she had signed the lease, and engaged a chaperon; but when she found that her aunt had accepted an invitation from Edward to bring her to dine with him at the Clarendon Hotel, and afterwards to go to the theatre at his expense, she was so indignant (having herself declined the invitation) that she could no longer restrain her annoyance.

Mrs. Hendred received the news with horrified incredulity. From her first disjointed ejaculations it was hard to decide whether it was her niece’s determination to embrace a life of spinsterhood that most shocked her, or the deplorably dowdy locality she had chosen for her asylum. The repulsive accents in which she repeated the words, Hans Town? could scarcely have held more disgust had she been speaking of a back-slum; and she several times reiterated the disgusting syllables, interjecting them between assurances that Venetia’s uncle would never countenance so improper a scheme. But she presently saw that although Venetia was listening to her with civility her mind was made up, and she exclaimed, with a sudden change of tone: “Oh, my dearest child, indeed, indeed you must not do it! You would regret it all your life—you can have no notion—you are still young, but only think what it would be like when you are growing old— the loneliness—the mortification of—” She broke off as a quiver ran over Venetia’s face, and leaned forward in her chair to lay one of her plump little hands on Venetia’s. “My dear, marry Mr. Yardley!” she said urgently. “I am persuaded you would be happy, for he is so kind and good, and in every way so eligible!”

The slim hand under hers was rigid; Venetia said in a constricted voice: “Pray do not say any more, ma’am! I don’t love Edward—and that must be the end of the matter.”

“But, dearest, I assure you you are mistaken! It is not in the least necessary that you should love him, for the happiest marriages frequently start with only the most moderate degree of affection! Indeed, I have known several where the couples were barely acquainted, but were content to let their parents arrange the match. You know, my love, girls cannot be better able to judge of what will suit them than their parents!”

“But I am not a girl, ma’am, and I have no parents.”

“No, but— Oh, Venetia, you don’t know what a mistake you would be making!” exclaimed Mrs. Hendred despairingly. “It would be better to marry a man one positively disliked than to remain a spinster! And how are you to make a respectable match if you go to live in Hans Town, and in such a peculiar style? For, after all, even with a disagreeable husband, though of course it would have grave drawbacks to be married to a disagreeable man, you would be a woman of consequence, and you would have all the comfort of your children, which, you know, is a female’s greatest interest—and, in any event, Mr. Yardley is not disagreeable! He is a most amiable person, values you just as he should, and, I daresay, would do everything in his power to make you happy! To be sure, he is not a lively man, but what husband is, after all? If you had fancied Sir Matthew, or Mr. Armyn, or even Mr. Foxcott, though I very much doubt whether he— But I can’t help feeling, dear child, that Mr. Yardley is the very man for you! He understands you so well, and knows what your circumstances are, so that there wouldn’t be an difficulty or awkwardness—and you would be living near your brother, and your friends, and in just the style to which you are accustomed, only not, of course, at Undershaw, but, still, in the country you know! You would feel yourself to be going home!”

“I don’t wish to go home!” The words were wrung from Venetia, and although quietly spoken were charged with anguish. She got up quickly, saying: “I beg your pardon—pray excuse me! There are circumstances—I can’t explain, but I beg you, ma’am, not to say any more! Only believe that I do know what must be the—the disadvantages of the course I am determined to pursue! I’m not so green that—” Her voice failed; she turned, and went with hurried steps to the door.

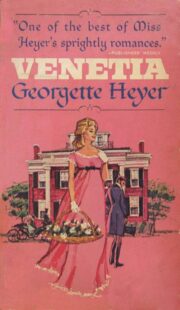

"Venetia" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Venetia". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Venetia" друзьям в соцсетях.