“No, I don’t wish to hurt you. I never wished to hurt you. The devil of it was, my dear delight, that you were too sweet, too adorable, and what should have been the lightest and gayest of flirtations turned to something more serious than I intended—or foresaw—or even desired! We allowed ourselves to be too much carried away, Venetia. Did you never feel you were living in a dream?”

“Not then. Now I do. This doesn’t seem real to me.”

“You are too romantic! We have been dwelling in Arcadia, my green girl: the rest of the world is not so golden as this retired spot! Only in fantasy does every circumstance conspire to make it inevitable that two people should fall in love! We should hardly have been more isolated had we been cast on a desert island together. Nothing happened to disturb our idyll, no person intruded on us: for one magical month we forgot—or I forgot—every worldly consideration, even that there are other things in real life than being sunk in love!”

“But it was real, for it happened, Damerel.”

“Yes, it happened. Let us agree that it was a lovely interlude! It could never be more than that, you know: we must have come to earth—we might even have grown a little weary of each other. That’s why I say that your uncle’s arrival is well-timed: parting is such sweet sorrow—but to fall out of love—oh, no, what a drab and bitter ending that would be to our autumn idyll! We must be able to look back smilingly, my dear delight, not shuddering!”

“Tell me one thing!” she begged. “When you talk of worldly considerations are you thinking of your past life?”

“Why, yes—but of other considerations too! I don’t think I should make a good husband, my dear, and nothing else is possible. To be frank with you, providence, in Aubrey’s shape, intervened yesterday just in time to save us both from disaster.”

She raised her eyes to his face. “You told me yesterday that you loved me—to the edge of madness, you said. Was that what you meant? that it was not real, and couldn’t endure?”

“Yes, that’s what I meant,” he said brusquely. He came back to her, and grasped her wrists. “I told you also that we would talk of it when we were cooler: well, my love, the night brings counsel! And the day has brought your uncle—and there let us leave it, and say nothing more than since there’s no help, come let us kiss, and part!”

She lifted her face in mute invitation; he kissed her, swiftly and roughly, and almost flung her away. “There! Now go, before I take still worse advantage of your innocence!” He strode over to the door, and wrenched it open, shouting to Imber to send a message to Nidd to bring Miss Lanyon’s mare up to the house. He turned, and she saw the ugly, mocking sneer on his face, and involuntarily looked away from him. He gave a jeering little laugh, and said: “Don’t look so tragic, my dear! I assure you it won’t be very long before you will be thanking God to be well out of the devil’s own scrape. You won’t fall into another, so don’t hate me: be grateful to me for opening your beautiful eyes a little! So very beautiful they are—and about the eyelids much sweetness! You’ll make a hit in London: the young eagles will say you are something like—adiamond of the first water—and so you are, my lovely one!”

The sense of struggling through the thickets of a nightmare again swept over her. There was a way out, so her heart’s voice cried to her, and could she find it she would find also Damerel, her dear friend. But time was slipping away; in another minute it would be too late; and urgency acted not as a spur but as a creeping paralysis which clogged the mind, and weighted the tongue, and imposed on desperation a blanket of numb stupidity.

Suddenly Damerel spoke again, in his own voice, as it seemed to her, and abruptly: “Does Aubrey go with you?” She looked blindly at him, and said, as though trying to recall to mind a name long-forgotten: “Aubrey ...”

“To London!”

“To London,” she repeated vaguely. She passed her hand across her eyes. “Yes, of course—how foolish! I had forgotten. I don’t know. He went out. He went out shooting before my uncle came.”

“I see. Does your uncle invite him?”

“Yes. But he won’t go—I think he won’t go.”

“Do you wish for him?”

She frowned, trying to concentrate her mind. The thought of Aubrey steadied her. She pictured him in such a household as she guessed her uncle’s to be, flayed by her aunt’s well-meaning solicitude, bored by her attempts to entertain him, contemptuous of all that she believed to be of the first importance; and presently said in a decided tone: “No. Not in Cavendish Square. It wouldn’t do for him. Later, when I shall have made arrangements—I told you, didn’t I? I must hire a house—someone to lend me countenance—make a home for myself and Aubrey, for it is so stupid to say, as Edward does, that Aubrey ought to like what he detests, because other boys do. Aubrey is himself, and no one can alter him, so what is the use of saying he ought, when he won’t?”

“No use at all. Let him come to me! Tell him he may bring his dogs, and his horses—whatever he chooses! I’ll engage myself to see he comes to no harm, and hand him over to that grinder of his in good trim. If he were here you wouldn’t fret yourself to flinders over him, would you?”

“No.” Her smile went pitifully awry. “Oh, no, how could I? But—”

“That’s all!” he interrupted harshly. “You won’t be beholden to me, you know! I shall be glad of his company.”

“But—you are remaining here?”

“Yes, I’m remaining here. Come! Nidd should have saddled up for you by now!”

She remembered that he had sent for his agent on business which he had said was important; and wondered if he had discovered his affairs to be in a worse state than he had guessed. She said diffidently: “I think you never meant to do so, and that makes me afraid that perhaps the business you have been engaged in hasn’t prospered?”

The sneer that mocked himself returned to his face; he gave a short laugh, and replied: “Don’t trouble your head over that, for it is not of the smallest consequence!”

He was holding open the door, a suggestion of impatience in his attitude. The second line of the sonnet he had quoted came into her mind: Nay, I have done: you get no more of me. He had not spoken those words; there was no need: a golden autumn had ended in storm and drizzling rain, an iridescent bubble had burst, and nothing was left to her but conduct, to help her to behave mannerly. She picked up her gloves and her whip, and walked out of the saloon, and across the flagged hall to the open entrance-door. Imber was standing by it, and through it she could see Nidd, holding her mare’s bridle. She was going to say goodbye to Damerel, her friend and her love, watched by these two, and it did not seem to her as though she would be able to speak at all, because her throat was aching quite dreadfully. She stepped out into the open, and turned to him, drawing a painful breath.

He was not looking at her, but at a black cloud looming to the west. “The devil!” he exclaimed. “You’ll never reach Undershaw before that comes down on you! What chance of its clearing, Nidd?”

Nidd shook his head. “Setting in wet, m’lord. Spitting already.”

Damerel looked down at Venetia, not sneering now, but concerned, ruefully smiling. He said, lowering his voice to reach only her ears: “You must go immediately, my dear. I can’t send you home in my carriage: it wouldn’t do! If that woman knew—!”

“It is of no consequence.” She put out her hand; she was very pale, but the flicker of her sweet smile warmed her eyes. “Goodbye—my dear friend!”

He did not answer, but only kissed her hand, and, holding it still, led her immediately to her mare. He tossed her up into the saddle, as he had done so many times when she had come to visit Aubrey, but today there was no lingering to make a plan for the morrow; he only said: “Take the short way, and don’t dawdle! I only hope you may not be drenched! Off with you, my child!”

He stepped back as he spoke, and the mare, needing no urging to go home to her own stable, started forward. Damerel lifted a hand in farewell, but Venetia was not looking at him, and he let it fall, and turned sharply on his heel. His eyes fell on Imber; he said in a curt, hard voice: “Miss Lanyon is going to London. It’s probable Mr. Aubrey will come here tomorrow, to stay for some few weeks. Tell Mrs. Imber to make his room ready!”

He strode away to the library, and the door shut with a snap behind him. Imber looked to see what Nidd made of this, not that he was likely to say, because he was as close as Marston, and dull as a beetle. Nidd was walking off to the stables, so there was nobody to gossip with but Mrs. Imber, and she was in a bad skin, because her dough hadn’t risen, and only said: “Don’t come fidgeting me!” and: “Get out of my way, do!” Imber wished himself at Undershaw, to see what they made of it there, when Miss Venetia came in looking like she’d seen a ghost. Proper set-about they’d be, and no wonder!

But only three people at Undershaw saw Venetia upon her return, and neither the undergroom nor the young housemaid who waited on her noticed more than her dripping habit, and the ruin of her hat, with its curled feather hanging sodden and straight beside her rain-washed face. She went up the backstairs to her room, and opened the door to find the maid there, with Nurse, and the room a welter of silver paper, and trunks, with gowns and cloaks laid out on the bed ready to be packed, the linen in which her furs had been stored all summer lying in a heap on the floor, and the sour apples which had kept the moth at bay scenting the air.

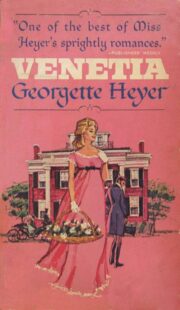

"Venetia" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Venetia". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Venetia" друзьям в соцсетях.