“Undoubtedly, ma’am.”

“Doing it rather too brown, m’dear!” said Aubrey, a glint in his eye. “You’ll still be first in consequence at Undershaw if you eat your dinner in the kitchen, and well you know it!”

“What a devoted brother!” remarked Mrs. Scorrier, with a slight titter.

“What a nonsensical one!” retorted Venetia. “Do you like to sit near the fire, ma’am, or will you—”

“Mrs. Scorrier ought to sit at the bottom of the table,” said Aubrey positively.

“You mean the foot of the table: opposite to the head, you understand,” said Mrs. Scorrier instructively.

“Yes, of course,” replied Aubrey, looking surprised. “Did I say bottom? I wonder what made me do that?”

Venetia asked Charlotte if she had enjoyed her visit to Paris. It was the first of the many hasty interventions she felt herself obliged to make during the course of what she afterwards bitterly described as a truly memorable dinner-party, for while Aubrey offered no unprovoked attacks he was swift to avenge any hint of aggression. Since he made it abundantly plain that he had constituted himself his sister’s champion, and won every encounter with the foe, Venetia could only suppose that Mrs. Scorrier was either very stupid, or compelled by her evil genius to court discomfiture. She really seemed to be incapable of resisting the temptation to depress Venetia’s imagined pretensions, so the dining-room rapidly became a battlefield on which (Venetia thought, with an irrepressible gleam of amusement) line inevitably demonstrated its superiority to column. Unable to counter Aubrey’s elusive tactics, Mrs. Scorrier attempted to give him a heavy set-down. Bringing her determined smile to bear on him she told him that no one would ever take him and Conway for brothers, so unlike were they. What unflattering comparisons she meant to draw remained undisclosed, for Aubrey instantly said, with a touch of anxiety: “No, I don’t think anyone could, do you, ma’am? He has the brawn of the family, I have the brain, and Venetia has the beauty.”

After this it was scarcely surprising that Mrs. Scorrier rose from the table with her temper sadly exacerbated. When she disposed herself in a chair by the drawing-room fire there was a steely look in her eyes which made her daughter quake, but her evident intention of making herself extremely unpleasant was foiled by Venetia’s saying that since it behoved her to write two urgent letters she hoped Charlotte would forgive her if she left her until tea-time to the comfort of a quiet evening with only her mama for company. She then left the room, and went to join Aubrey in the library, saying, with deep feeling, as she entered that haven: “Devil!”

He grinned at her. “What odds will you lay me that I don’t rid the house of her within a se’ennight?”

“None! It would be robbing you, for you won’t do it. And, indeed, love, you might consider Charlotte’s feelings a trifle! She may be a ninnyhammer, but she can’t help that, and her disposition, I am quite convinced, is perfectly amiable and obliging.”

“So sweetly mawkish and so smoothly dull, is what you mean to say!”

“Well, at least the sweetness is something to be thankful for! Do you wish to use your desk? I must write to Aunt Hendred, and to Lady Denny, and I haven’t had the fires lit in the saloon, or the morning-room.”

“You haven’t had them lit?” he said pointedly.

“If you don’t wish to see me fall into strong hysterics, be quiet!” begged Venetia, seating herself at the big desk. “Oh, Aubrey, what a shocking pen! Do, pray, mend it for me!”

He took it from her, and picked up a small knife from the desk. As he pared the quill he said abruptly: “Are you writing to tell my aunt and the Dennys that Conway is married?”

“Of course, and I do so much hope that with Lady Denny at least I shall be beforehand. My aunt is bound to read it in the Gazette—may already have done so, for that detestable woman tells me she sent in the notice before she left London! You’d think she might have waited a few days longer, after having done so for three months!”

He gave the pen back to her. “Conway wasn’t engaged to Clara Denny, was he?”

“No—that is, certainly not openly! Lady Denny told me at the time that they were both of them too young, and that Sir John wouldn’t countenance an engagement until Conway was of age and Clara had come out, but there’s no doubt that he would have welcomed the match, and no doubt either that Clara thinks herself promised to Conway.”

“What fools girls are!” he exclaimed impatiently. “Conway might have sold out when my father died, had he wished to! She must have known that!”

Venetia sighed. “You’d think so, but from something she once said to me I very much fear that she believed he remained with the Army because he thought it to be his duty to do so.”

“Conway ? Even Clara Denny couldn’t believe that moonshine!”

“I assure you she could. And you must own that anyone might who was not particularly acquainted with him, for besides believing it himself, and always being able to think of admirable reasons for doing precisely what suits him best, he looks noble!”

He agreed to this, butsaid after a thoughtful moment: “Do I do that, m’dear?”

“No, love,” she replied cheerfully, opening the standish. “You merely do what suits you best, without troubling to look for a virtuous reason. That’s because you’re odiously conceited, and don’t care a button for what anyone thinks of you. Conway does,”

“Well, I’d a deal rather be conceited than a hypocrite,” saidAubrey, accepting this interpretation of his character with equanimity. “I must say I look forward to hearing what the reason was for this havey-cavey marriage. Come to think of it, what was the reason? Why the deuce didn’t he write to tell us? He knew he must tell us in the end! Too corkbrained by half!”

Venetia looked up from the letter she had begun to write. “Yes, that had me in a puzzle too,” she admitted. “But I thought about it while I was dressing for dinner, and I fancy I have a pretty fair notion of how it was. And that is what makes me afraid that the news will come as a shocking blow to poor Clara. I think Conway did mean to offer for Clara. I don’t mean to say that he was still in that idiotish state which made him such a bore when he was last at home, but fond enough of her to think she would make him a very agreeable wife. What’s more, I should suppose that there had been an exchange of promises, however little the Dennys may have suspected it. If Conway thought he was in honour bound to offer for Clara I see just why he never wrote to us.”

“Well, I don’t!”

“Good God, Aubrey, you know Conway! Whenever there’s a difficult task to be performed he will put off doing anything about it for as long as he possibly can! Only think how difficult it must have been to write to tell me that in the space of one furlough he had met, fallen in love with, and married a girl he never saw before in his life, and had jilted Clara into the bargain!”

“Knew he’d made a cod’s head of himself. Yes, he wouldn’t like that,” said Aubrey reflectively. “I suppose Charlotte was on the catch for him.”

“Not she, but Mrs. Scorrier most certainly—and had no intention of letting him slip through her fingers! She was responsible for that hasty marriage, not Conway—and I give her credit for being shrewd enough to guess that if she did not tie the knot then, the chances were that he would forget Charlotte in a month! And when it was clone, I daresay he meant to write to me—not that day, but the next! And so it went on, just as when he put off for the whole of one holiday breaking it to Papa that he wished him to buy him a pair of colours, instead of sending him up to Oxford—yes, and in the end I had to speak to Papa, for Conway had gone back to Eton! On this occasion there was no one to act for him, and I haven’t the least doubt that he postponed writing until it must have seemed quite impossible to write at all. Perhaps he then persuaded himself that it would be better not to write, but to bring Charlotte home with him, trusting to chance or our pleasure at having him restored to us to make all right! Only Mrs. Scorrier scotched that scheme, by quarrelling with some Colonel or other, and making things so awkward for Conway that he saw nothing for it but to be rid of her on any terms. You can’t doubt she would have kicked up a tremendous dust if he had tried to send her packing without Charlotte, and he would never face her doing that at Headquarters!”

“So he sent Charlotte home with her,” said Aubrey, his lips beginning to curl. “You were wrong, stoopid! There was someone to break the news for him! What a contemptible fellow he is!”

With this he stretched out a hand for the book that was lying open on a table, and immediately became absorbed in it, while Venetia, amused by his detachment and a little envious of it clipped her pen in the ink again, and resumed her letter to Mrs. Hendred.

XII

Venetia awoke on the following morning conscious of a feeling of oppression which was not lightened by the discovery, ‘presently, that her sole companion at the breakfast-table was Mrs. Scorrier. Charlotte being still in bed, and Aubrey having told Ribble to bring him some coffee and bread-and-butter to the library. Mrs. Scorrier greeted her with determined affability, but roused in her a surge of unaccustomed wrath by inviting her to say whether she liked cream in her coffee. For a moment she could not trust herself to answer, but she managed to overcome what she told herself was disproportionate fury, and replied that Mrs. Scorrier must not trouble to wait on her. Mrs. Scorrier, momentarily quelled by the sudden fire in those usually smiling eyes, did not persist, but embarked on an effusive panegyric which embraced the bed she had slept in, the view from her window, and the absence of all street noises. Venetia responded civilly enough, but when Mrs. Scorrier expressed astonishment that she should permit Aubrey to eat his breakfast when and where it pleased him, the tone in which she replied: “Indeed, ma’am?” was discouraging in the extreme.

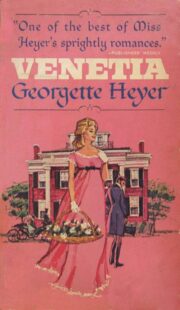

"Venetia" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Venetia". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Venetia" друзьям в соцсетях.