Damerel pulled the gray up, and surveyed his youthful foe sardonically. “All that is needed to complete the picture is a mask and a pair of horse-pistols,” he remarked.

“I have been waiting for you, my lord!” said Oswald, gritting his teeth.

“I see you have.”

“I imagine your lordship must know why! I said—I told you that you should hear from me!”

“You did, but you’ve had time enough to think better of it. Try for a little wisdom, and go home!”

“Do you think I’m afraid of you?” Oswald demanded fiercely. “I’m not, my lord!”

“I can see no reason why you should be,” said Damerel. “You must know that there’s not the least possibility of my accepting a challenge from you.”

Oswald flushed. “I know nothing of the sort! If you mean to say I’m unworthy of your sword I’ll take leave to tell you, sir, that I’m as well-born as you!”

“Don’t rant! How old are you?”

Oswald glared at him. There was a derisive gleam in the eyes which scanned him so indifferently, and it filled him with a primitive longing to smash his fist between them. “My age is of no consequence!” he snapped.

“On the contrary: it is of the first consequence.”

“Here it may be! I don’t regard that, and you need not either! I have been about the world a little, and visted places where—” He stopped, suddenly recollecting that he was talking to a man who had travelled widely.

“If you have visted places where men of my years accept challenges from boys who might well be their sons you must have strayed into some pretty queer company,” remarked Damerel.

“Well, anyway, I’m reckoned to be a fair shot!” said Oswald.

“You terrify me. On what grounds do you mean to issue this challenge?”

The angry young eyes held his for an instant longer, and then looked away.

“I won’t press you for an answer,” said Damerel.

“Wait!” Oswald blurted out, as Crusader moved forward. “You shan’t fob me off like that! I know I ought not to have— I never meant—I don’t know how I came to— But there was no need for you to—”

“Go on!” said Damerel encouragingly, as Oswald broke off. “No need for me to rescue Miss Lanyon from a situation which she was plainly not enjoying? Is that what you mean?”

“Damn you, no!” Oswald sought for words to express the hopeless tangle of his thoughts; none came to him, only the age-old cry of youth: ‘‘You don’t understand!”

“You may ascribe the astonishing guard I have so far kept over my temper to the fact that I do,” was the rather unexpected reply. “Patience, however, was never numbered amongst my few virtues, so the sooner we part the better. I am very sorry for you, but there’s nothing I can do to help you recover from these pangs, and your inability to open your mouth without going off into rodomontade does rather alienate my sympathy, you know.”

“I don’t want your damned sympathy!” Oswald flung at him, intolerably stung. “One thing you can do, my lord! You can stop trying to give Venetia a slip on the shoulder!” He saw the flash in Damerel’s eyes, and hurried on recklessly: “W-walking into her house as though it were your own, cajoling her with your man-of-the-town ways, c-cutting a wheedle with her because she’s too innocent to know it’s all a rig, and you’re bamboozling her! T-talking to me as if I was the loose-screw! I m-may have lost my head but I mean honestly by her! And you needn’t think I don’t know it’s uncivil to say things like this to you, because I do, and I don’t care a rush, and if you choose to nab the rust you may do so—in fact, I hope you will!— And I don’t care if you tell my father I’ve been uncivil to you either!”

Damerel had been looking a little ugly, but this sudden anticlimax dispelled his wrath, and made him laugh. “Oh, I won’t proceed to such extreme measures as that!” he said. “If there were a horse-pond at hand—! But there isn’t, and at least you’ve made me a speech without any high-flown bombast attached to it. But unless you have a fancy for eating your dinner with your plate on the mantelpiece for the next few days don’t make me any more such speeches!”

Oswald gave a gasp of outrage. “Only dismount, and we’ll try that!” he begged.

“My deluded youth, that is being more childish valourous than manly wise: I’m sure you’re full of pluck, and equally sure that it would be bellows to mend with you in rather less than two minutes. I’m not a novice, you see. No, keep your mouth shut! It is now my turn to make a speech! It will be quite short, and, I trust, quite plain! I’ve borne with you because I haven’t forgotten the agonies of first love, or what a fool I made of myself at your age; and also because I perfectly understand your desire to murder me. But when you have the infernal impudence to tell me I can stop trying to seduce Miss Lanyon you’ve gone very far beyond the line of what I’ll take from you! Only her brother has the right to question my intentions. If he chooses to do it I’ll answer him, but the only answer I have for you is contained in the toe of my boot!”

“Her brother isn’t here!” Oswald retorted swiftly. “If he were it would be a different matter!”

“What the devil— Oh, you’re talking of her elder brother, are you? I wasn’t.”

“Aubrey?” exclaimed Oswald incredulously. “That scrubby little ape? Much good he could do—even if he tried! What does he know about anything but his fusty classics? If he thought about it at all he wouldn’t have the least notion what sort of a game you’re playing!”

Damerel gathered up his bridle, saying dryly: “Don’t despise him on that head! Neither have you the least notion.”

“I know you don’t mean marriage!” Oswald retorted.

Damerel looked at him for a moment, an oddly disquieting smile in his eyes. “Do you?” he said.

“Yes, by God I do!” As Crusader moved forward, Oswald wrenched his own horse round, staring after Damerel in sudden dismay. He stammered: “Marriage? You and Venetia? She wouldn’t—she couldn’t!”

There was undisguised revulsion in his voice, but the only response it drew from Damerel was a laugh, as he turned Crusader in through the gateway of the Priory, and cantered away down the long weed-grown avenue.

Oswald could hardly have been more shocked had Damerel openly declared the most dishonourable of intentions. He was left a prey to doubt and disbelief, and with no other course open to him than to ride tamely home to Ebbersley. It was a long, dull ride, and with only the most humiliating reflections to occupy his mind he very soon became so sunk in gloom that not even the knowledge that his last words at least had flicked Damerel on the raw would have done much to elevate his spirits.

Marston, gathering up Damerel’s discarded coat and breeches, looked thoughtfully at him, but offered no comment, either then or much later, when he found Imber, an expression of long-suffering on his face, decanting a bottle of brandy.

“On the cut!” said Imber. “I thought it wouldn’t be long before he was making indentures. He’s finished the Diabolino, what’s more, so if he doesn’t relish what was always good enough for his late lordship it’s no manner of use for him to blame me. I told him a se’ennight past how it was.”

“I’ll take it to him,” Marston said.

Imber sniffed, but raised no demur. He was an old man, and his feet hurt him. He always accepted Marston’s services, but thought poorly of him for undertaking tasks which lay outside his province. Quite menial tasks, some of them: he made nothing of fetching in logs for the fires, or even of sawing them up; and had been known, when Nidd was absent, to unsaddle his master’s horse, and rub him down. You wouldn’t have caught the late lord’s valet so demeaning himself, thought Imber, contrasting him unfavourably with that most correct of gentlemen’s gentlemen! Like master like man, he thought. Stiff-rumped the late lord had been; he knew what was due to his consequence, and always kept a proper distance. No one ever dared to take any liberties with him, any more than he ever talked to his servants in the familiar way the present lord used. As for arriving at the Priory without a word of warning, and accompanied only by his valet and his groom, and taking up a protracted residence there with more than half the rooms shut up, and not so much as a single footman to lend respectability to the household, imagination boggled at the very idea of his late lordship behaving so improperly. It all came of living in foreign parts, amongst people who like as not were little better than savages. That was what his present lordship had said, when he had ventured to give him a hint that the terms he stood on with Marston were unseemly in a gentleman of his position. “Marston and I are old friends,” he had said. “We’ve been in too many tight corners together to stand on ceremony.” It was no wonder that Marston thought himself above his company, and was too top-lofty to indulge in comfortable gossip about his lordship. He was pleasant enough, in his quiet way, but close as wax, and with a trick of seeming not to hear what he didn’t choose to answer. If he was so out of reason fond of his lordship why didn’t he speak up for him instead of looking like a wooden image? thought Imber resentfully, watching him pick up the salver, and carry it away, down the stone-flagged passage that led to the front hall.

Damerel did not keep town-hours at the Priory; he allowed the Imbers to serve dinner at six o’clock; and, since Aubrey’s arrival, he had abandoned his tiresome habit of lingering in the dining-room over his port, but had carried it up to Aubrey’s room while Aubrey was confined to bed, and later had fallen into the way of drinking it in the library. Tonight, however, he had shown no disposition to leave the table, but sat lounging in his great, carved chair as though he meant to stay there all night.

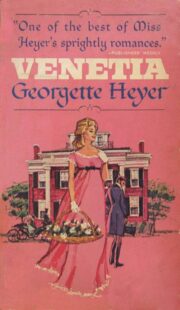

"Venetia" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Venetia". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Venetia" друзьям в соцсетях.