“She sounds very disagreeable!”

“She is very disagreeable. A veritable dragon!”

“But why does she wish to re-establish you?”

“Oh, for two reasons! The first is that however black my sins may be I’m the head of the family, a circumstance by which she sets great store; and the second is that having issued a royal command to my cousin Alfred, who is also my heir, to present himself in Grosvenor Square for inspection, she made the shocking discovery that he was a member of the dandy-set—indeed, the pinkest of Pinks, a swell of the first stare! Not having the least guess that the old lady holds every Bond Street beau in the utmost abhorrence, the silly pigeon rigged himself out as fine as fivepence, and trotted round to Grosvenor Square looking precise to a pin: Inexpressibles of the most delicate shade of primrose, coat by Stulz, Hessians by Hoby, hat—the Bang-up—by Baxter, neckcloth—the Oriental, which is remarkable for its height— by himself. Add to all this a Barcelona handkerchief, a buttonhole as large as a cabbage, a strong aroma of Circassian hair-oil, the deportment of a dancing-master, and a lisp it took him years to bring to perfection, and you will perceive that Alfred is not just in the ordinary style!”

“I wish I might see him!” she said, laughing. “Did you, or is this make-believe?”

“Certainly not! I didn’t see him, but what he didn’t describe to me my aunt did. Poor fellow! he was only bent on doing the pretty, but all his hopes were cut up! The breach was to have been healed—oh, I didn’t mention, did I, that my aunts had quarrelled with his mother? I believe she offended them on the occasion of my uncle’s obsequies, but as I was not present I don’t know what crime she committed, though I wouldn’t bet against the chance that she didn’t render proper respect to their consequence. In any event, Alfred obeyed my Aunt Augusta’s summons, confident that the exercise of a little address—coupled, of course, with his exquisite appearance—would decide not only her, but my Aunts Jane and Eliza as well, to make him their heir—which is a matter of very much more interest to him than his being my heir, pour cause! But alas! faced with the choice between a fop and a rip they preferred the rip—or they would, if I’d be comformable!”

“Behave with propriety?”

“Worse! Marry a butter-toothed female with a pug-nose and a deplorable figure!”

She laughed. “Well, I daresay they wish you to be married, because that would be the most respectable thing you could do, and also, of course, on account of children, so that your cousin would be quite cut out—but I see no reason why she should be pug-nosed, or butter-toothed!”

“Nor I, but she’s both, I promise you. What’s more, she’s been an ape-leader for ten years at least. Do you wonder that I fled?”

“No, but I do wonder that your aunts should have been so gooseish as to have proposed such a match to you! They must be quite addle-brained to suppose that you would look twice at any but the most ravishing females, for you have been used only to be in love with beauties for years and years! It is most unreasonable to expect people to change their habits in the twinkling of an eye.”

“Very true!” he agreed, admirably preserving his countenance. “And Miss Amelia Ubley’s eye has as much twinkle as may be seen in the eye of a fish.”

“Then on no account must you offer for her!” she said earnestly. “I am excessively sorry for her, poor thing, but she would be far happier as an old maid than as your wife! I shouldn’t wonder at it if you made off with someone else before the bride-visits had all been paid, and only think how mortifying for her. How came your aunts to hit upon such an unsuitable female for you? They must have a great deal more hair than wit!”

His lips twitched, but he replied gravely: “I fancy they consider me to be past the age of romantic indiscretions. My Aunt Eliza, at all events, tells me that it is now time I settled-down. She drew for me a very moving picture of the advantages of becoming regularly established.”

“I can see she did. It moved you all the way to Yorkshire! Pray, what are Miss Ubley’s virtues?”

“Well—virtue!”

“That won’t do in the least. Not if you mean that she’s strait-laced, and she sounds to me as if she would be.”

“That’s what she both sounded and looked like to me. However, my aunts informed me that besides being of the first respectability she has superior sense, propriety of taste, and can be trusted to behave always just as she ought. Her fortune is as good as I have any right to expect; and I must remember that if she were not above thirty years of age, and an antidote, neither she nor her parents would entertain my proposal for a minute.”

“What moonshine!” exclaimed Venetia indignantly.

There was a good deal of the sneer in the half-smile he threw her. “No, that was true enough. I imagine I must rank high on the list of ineligible bachelors—which has this advantage: that there is no need for me to take care lest I fall a prey to a matchmaking mama. It is she who warns her daughter that if she should chance to find herself in company with me she must keep a proper distance.”

“Then you do go to parties?” she asked. “I am very ignorant about society, and what you call the ton, and when you said you were a social outcast I thought perhaps it meant you didn’t go into polite circles at all.”

“Oh, it isn’t as bad as that!” he assured her. “I’m certainly not invited to run tame in houses where the daughters are of marriageable age, and I can think of nothing more unlikely than of being permitted to cross the sacred threshold of Almack’s—unless, of course, I reformed my way of life, married Miss Ubley, and was sponsored by my Aunt Augusta into that holy of holies—but only the very highest sticklers go to the length of cutting my acquaintance! If anything were wanting to make me flee from Miss Ubley’s vicinity it would be the dread of being dragged into precisely those circles from which I am most happy to be excluded!”

“I must say, from all Lady Denny has told me I should suppose the Assemblies at Almack’s to be amazingly dull,” she observed. “When I was a girl it was used to be the top of my ambition to attend them, but I think now that I should find them insipid.”

But this he would not allow. He scolded her for speaking of her girlhood as a thing of the past, and said: “When your brother comes home you’ll go on a visit to that aunt of yours, and you will enjoy yourself very much. You will be gay to dissipation, my dear delight, going to all the fashionable squeezes, breaking a great many hearts, and finding every day too short for all the pleasuring you wish to cram into it.”

“Oh, when that day dawns I shall very likely be in my dotage!” she retorted.

VIII

Edward Yardley, secure in the knowledge of his own worth, might rate Damerel cheap, but young Mr. Denny, by no means so self-confident as he tried to appear, recognized in him both amodel and a menace. Like Edward, he rode over to the Priory to enquire how Aubrey did; unlike Edward, he no sooner clapped eyes on Damerel than he became possessed of a deep and envious hatred.

Imber ushered him into the library, where Damerel and Aubrey were playing chess, with Venetia seated on a stool by the sofa, watching the game. This cosy scene afforded him no pleasure at all; and when Damerel rose, and he saw how tall he was, with what careless grace he moved, and how much lazy mockery lurked in his eyes, he knew that his sisters had grossly misled him: they had thought his lordship dull and middle-aged; Oswald perceived at one glance that he was a dangerous marauder.

His visit was not of long duration, but it lasted for quite long enough to enable him to see on what easy terms of intimacy the Lanyons were with their host. They were not only perfectly at home in his house, but they behaved as though they had known him all their lives. Aubrey even called him Jasper; and although Venetia did not go to such outrageous lengths as that she used no formality when she spoke to him. As for Damerel, Nurse might think his attitude avuncular, but Oswald, his perception sharpened by jealousy, was not deceived. When his eyes rested on Venetia there was an expression in them very far from avuncular, and when he addressed her there was a caress in his voice. Oswald glared at him, and tried in vain to think of some adroit way of getting himself and Venetia out of the room. None occurred to him, so he was forced to employ direct tactics, saying rather throatily, and with reddening cheeks, as he shook hands in farewell: “May I speak to you for a moment?”

“Yes, of course you may!” Venetia replied kindly. “What is it?”

“Don’t be gooseish, m’dear!” recommended Aubrey, inspiring Oswald with a longing to wring his neck.

“You have a message for her from Lady Denny, which you would prefer to deliver in private, haven’t you?” suggested Damerel helpfully, but with an unholy twinkle.

In a nobler age one could have answered such impertinence by jostling his lordship as he stood holding open the door, so that he would have been obliged to demand a meeting. Or did one, even in that age, refrain from jostling people in doorways when a lady was present?

Before he had decided this point he had followed Venetia into the hall, and Damerel had shut the door on them. He uttered tensely: “If I know myself, there will be a reckoning between us one day!”

Venetia was accustomed to his dramatic outbursts, but she found this one surprising. “Between us?” she asked. “Now, what in the world have I done to put you in a miff, Oswald?”

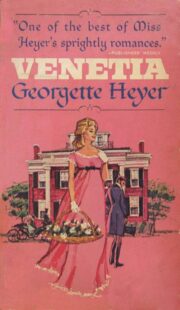

"Venetia" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Venetia". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Venetia" друзьям в соцсетях.