“Are you telling me that you ever entertained for as long as five minutes the thought of accepting such a clod-pole?” he demanded. “Good God, the fellow’s a dead bore!”

“He is, of course, but there’s no saying he wouldn’t be a good husband, for he is very kind, and honourable, and— and respectable, which I believe are excellent qualities in a husband.”

“No doubt! But not in your husband!”

“No, I believe we should tease one another to death. The thing was, you see, that because he was Papa’s godson Papa permitted him to visit us, and so we grew to know him very well, and when he wished to marry me I did wonder (though it was not at all what I wanted) whether perhaps it might not be better for me to do so than to grow into an old maid, hanging on Conway’s sleeve. However, if Aubrey dislikes him as much as that it won’t do. Oh dear, you have allowed your garden to grow into a wilderness! Only look at those rose-trees! They can’t have been pruned for years!”

“Very likely not. Shall I set a man on to attend to them? I will, if it would please you.”

She laughed. “Not at this season! But later I wish you will: it might be such a delightful garden! Where are you taking me?”

“Down to the stream. There’s a seat in the shade, and we can watch the trout rising.”

“Oh, yes, let us do that! Have you fished the stream this year? Aubrey once caught a three-pounder in it.”

“Oh, he did, did he?”

“Yes, but he wasn’t poaching, I assure you! Croyde gave him leave—he does so every year. You don’t fish it yourself, after all!”

“Now I know why I’ve had such poor sport each time I’ve taken my rod out! What a couple you are! First my blackberries, and now my trout!” he said.

The laughing devil was in his eyes, but she was not looking at him, and replied without a trace of embarrassment: “What a long time ago that seems!”

“And how angry you were!”

“I should rather think I was! Well, of all the abominable things to have done!”

“I didn’t find it so!”

She turned her head at that, looking up at him in a considering way, as though she were trying to read the answer to a problem in his face. “No, I suppose not. How very odd, to be sure!”

“What is?”

She walked on, her brow a little furrowed. “Wishing to kiss someone you never saw before in your life. It seems quite madbrained to me, besides showing a sad want of particularity.” She added charitably: “However, I daresay it is one of those peculiarities of gentlemen even of the first respectability which one cannot hope to understand, so I don’t refine too much upon it.”

He gave one of his sudden shouts of laughter. “Oh, not of the first respectability!”

They had emerged by this time from the rose-garden through an archway cut in the hedge on to the undulating lawns which ran down to the stream. Venetia paused, exclaiming: “Ah, this is a delightful prospect! Looking at the Priory from the other side of the river, one can’t tell that you have that distant view. I have never been here before.”

“I’ve seldom been here myself. But I prefer the nearer prospect.”

“Do you? Just green trees?”

“No, a green girl. That is why I’ve remained here. Had you forgotten?”

“I don’t think I am green. It’s true I only know what I’ve read in books, but I’ve read a great many books—and I think you are flirting with me.”

“Alas, no! only trying to flirt with you!”

“Well, I wish you will not. I conjecture that you came into Yorkshire to ruralize. Isn’t that what they call it, when you find yourself cleaned-out?”

“Not so very green!” he said, laughing. “That’s it, fair fatality!”

“If but one half the stories told about you are true you must be very expensive,” she observed reflectively. “Do you indeed keep your own horses on all the main post-roads?”

“I had need to be a Dives to do that! Only on the Brighton and Newmarket roads, I fear. What other stories do they tell of me? Or are they unrepeatable?”

She allowed him to guide her to a stone bench, under an elm tree, and sat down on it, clasping her hands loosely in her lap. “Oh, no! None that were told me, of course.” She turned her face towards him, her eyes brimming with mischief. “It was always We could an if we would whenever we tried—Conway and I—to discover why you were the Wicked Baron. That was our name for you! But no one would tell us, so we were obliged to resort to imagination You wouldn’t believe the crimes we saddled you with! Nothing short of piracy would do for us until Conway, who was always less romantic than I, decided that that must be impossible. I would then have turned you into a highwayman, but even that wouldn’t do for him. He said you had probably killed someone in a duel, and had been forced to flee the country.”

He had been listening to her in amusement, but at that his expression altered. He was still smiling, but not pleasantly, and although he spoke lightly there was a hard note in his voice. “But how acute of Conway! I did kill someone, though not in a duel. My father.”

She was deeply shocked, and demanded: “Who said that to you?” Then, as he merely shrugged, she said: “It was an infamous thing to have said! Idiotish, too!”

“Far from it. The news of my elopement caused him to suffer a stroke, from which he never recovered. Didn’t you know that?”

“Everyone knows it! And also that he died nearly three years later, of a second stroke. Were you accountable for that? To be sure, it was unfortunate you didn’t know he was likely to suffer a stroke, and so were the unwitting cause of it, but if you think he would not have succumbed to it sooner or later you can know very little about the matter! My father had a stroke too: his was fatal. It was not brought about by any shock, and it couldn’t have been averted.” She laid an impulsive hand on one of his, saying earnestly: “I assure you!”

He looked at her, queerly smiling, but whether he mocked himself or her she could not tell. “It doesn’t keep me awake o’ nights, my dear. Not much love was lost between us at the best of times.”

“I didn’t love mine either. In fact, I disliked him. You can’t think how comfortable it is to be able to say that and not fear to be told that I cannot mean it, or that it was my duty to love him! Such nonsense, when he never pretended to care a button for any one of us!”

“Yours seems to have given you little reason to love him, certainly,” he remarked. “Honesty compels me to say, however, that mine had a poor bargain in his only son.”

“Well, if I had an only son—or a dozen sons, for that matter!—I would find something better to do for him when he was in a scrape than cast him off!” declared Venetia. “Would not you?”

“Oh, lord, yes! Who am I to throw stones? I might even make a push to stop him getting into the scrape—though if he were to be half as infatuated as I was I daresay I should fail,” he said reflectively.

After a short pause, during which he seemed to her to be looking back across the years, and with no great pleasure, she ventured to ask: “Did she die?”

His eyes came back to her face, a little startled. “Who? Sophia? Not that I know of. What put that into your head?”

“Only that no one seems to know—and you didn’t marry her—did you?”

“Oh, no!” He saw the troubled look, and grimaced. “You want to know why, do you? Well, if such ancient history interests you, she was not, at the time of Vobster’s death, living under my protection. Oh, don’t look so dismayed!”

“Not dismayed—not that!” she stammered.

“Ah, you feel compassionate? Wasted, my dear! Our mutual passion was violent while it lasted, but soon wore itself out. Fortunately we were saved from dwindling into a state of mutual boredom by the timely appearance on our scene of an accomplished Venetian.”

“An accomplished Venetian!”

“Oh, of the first stare! Handsome, too, and all in print. Air and address were quite beyond my touch!”

“And fortune?” she interpolated.

“That, too. It enabled him to indulge the nattiest of whims! He drove and rode only gray horses, never wore any but black coats, and always, summer or winter, with a white camellia in his buttonhole.”

“Good God, what a quiz! How could she—Lady Sophia—have liked him?”

“Oh, make no mistake! he was a charming fellow! Besides, poor girl, she had become so devilish bored! Who could blame her for preferring an experienced Tulip to the callow tuft I was in those days? For the life of me I can’t conceive how she contrived to bear with my ardours and jealousies for as long as she did. There were no bounds to my folly: if you can picture Aubrey tail over top in love, I imagine I must have been in much the same style. Chuckfull of scholarship, and with no more commonsense than to bore her to screaming point with classical allusions! I even tried to teach her a little Latin, but the only lesson she learned of me was the art of elopement. She put that into practice before we had reached the stage of murdering one another— for which piece of prudence I’ve lived to thank her. She had her reward, too, for Vobster was so obliging as to break his neck before custom had staled her variety, and her Venetian was induced to marry her. I daresay she threatened to leave him, and he may well have despaired of finding another who would have blended so admirably with his taste for black and white. She had a milky complexion and black hair—raven’s wing black!—and eyes so dark as to appear black at least. A little plump beauty! I’m told she was never afterwards seen abroad except in white gowns and black cloaks, and I’ll swear the effect must have been prodigious!”

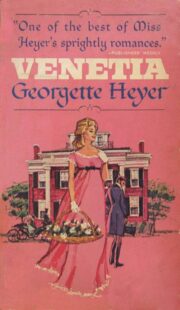

"Venetia" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Venetia". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Venetia" друзьям в соцсетях.