“One hesitates to speak ill of the dead,” persevered Edward, “but towards his children he displayed an almost total want of interest or consideration. One would have expected him to have provided his daughter with a chaperon, for instance, but such was not the case. You may have wondered, I daresay, at the freedom of Miss Lanyon’s manners, and, not knowing the circumstances, have thought it odd that she should be permitted to go abroad quite unattended.”

“No doubt I should, had I met her when she was a girl,” responded Damerel coolly. He turned his head, as Imber came into the hall. “Imber, here is Mr. Yardley, who has come to visit our invalid! Take him up—and see that Mrs. Priddy has that bundle of lint, will you?” He nodded to Edward to follow the butler, and himself walked off to one of the saloons that led from the hall.

Edward trod up the broad, shallow staircase in Imber’s wake, his feelings almost equally divided between relief at finding Damerel apparently indifferent to Venetia, and annoyance at the casual way he had been dismissed.

In general he ignored Aubrey’s frequent rudeness, but that scornful adjuration to him not to be a slow-top vexed him so much that he was obliged to suppress a sharp retort. He never allowed himself to speak hastily, and it was therefore in a measured tone that he said, after a moment: “Let me point out to you, Aubrey, that if you would not try to be quite such a hard-goer this unfortunate accident would never have occurred.”

“It was not, after all, so very unfortunate,” intervened Venetia. “How kind in you to have come to see how he does!”

“I must regard as unfortunate—to put it no higher!—an accident that places you in an awkward situation,” he said.

“Well, pray don’t tease yourself over that!” she said soothingly. “To be sure, I had rather Aubrey were at home, but I am able to visit him every day, you know, and he, I am persuaded, has not the least wish to be at home. I must tell you, Edward, that nothing could be greater than Damerel’s kindness to Aubrey, or his good nature in allowing Nurse to order everything precisely as she chooses here. You know her way!”

“You are very much obliged to his lordship,” he replied gravely. “I do not deny it, but you will scarcely expect me to think your indebtedness anything but an evil, the consequences of which may, I fear, be far-reaching.”

“What consequences? I hope you mean to tell me what you mean, for I promise you I don’t know! The only consequence I perceive is that we have made an agreeable new acquaintance—and find the Wicked Baron to be very much less black than rumour has painted him!”

“I make every allowance for your ignorance of the world, Venetia, but surely you cannot be unaware of the evil that attaches to acquaintance with a man of Lord Damerel’s reputation! I should not wish to make a friend of him myself, and in your case—which is one of particular delicacy—every feeling revolts against such an acquaintance!”

“Quousque tandem abutere, Catilina, patientia nostra?” muttered Aubrey savagely.

Edward glanced at him. “If you wish me to understand you, Aubrey, I fear you will be forced to speak in English. I do not pretend to be scholar.”

“Then I’ll give you a tag well within your power to translate! Non amo te, Sabidi!”

“No, Aubrey, pray don’t!” begged Venetia. “It is mere nonsense, and to be flying into a rage over it is the most nonsensical thing of all! Edward is only in one of his fusses over propriety—and so, let me tell you, is Damerel! For when you vexed poor Nurse so much that she threatened to leave you, my love, what must he do but tell her she must remain here to safeguard my reputation? Anyone might think I was a chit just emerged from the schoolroom!”

Edward’s countenance relaxed a little; he said, with a slight smile: “Instead of a staid and middle-aged woman? His lordship was very right, and I don’t hesitate to say that it gives me a better opinion of him. But I wish you will discontinue your visits to Aubrey. He is not so badly hurt as to make your attendance on him necessary, and if you come only to entertain him—well, I must say, however much you may resent it, Aubrey, that I think you deserve to be left to entertain yourself! Had you but listened to older and wiser counsel none of this awkwardness would have arisen. No one has more sympathy than I for the disability which makes it imprudent—indeed, I am afraid I must say foolhardy!—for you to attempt to ride such a headstrong animal as that chestnut of yours. I told you so at the outset, but—”

“Are you imagining that Rufus bolted with me?” interrupted Aubrey, his eyes glittering with cold dislike. “You’re mistaken! The plain truth is that I crammed him! A piece of bad horsemanship which had nothing to do with my disability! I’m well aware of it—don’t need to have it thrust down my throat!”

“That is certainly an admission!” said Edward, with an indulgent little laugh. “Neck-or-nothing, eh? Well, I don’t mean to give you a scold. We must hope your tumble has taught you the lesson you wouldn’t learn from me.”

“Much more likely!” Aubrey said swiftly. “I never dared learn of you, Edward: as well as your caution I might have acquired your hands—quod avertat Deus!”

It was at this moment that Damerel entered the room, saying cheerfully: “May I come in? Ah, your servant, Miss Lanyon!” He met her eyes for a brief instant, and continued in the easiest style: “I’ve told Marston to bring up a nuncheon for you to eat with Aubrey, and my errand is to discover whether you like to drink tea with it—and also to carry off your visitor to share my nuncheon.” He smiled at Edward. “Come and bear me company, Yardley!”

“Your lordship is very obliging, but I never eat at this hour,” Edward said stiffly.

“Then come and drink a glass of sherry,” replied Damerel, with unimpaired affability. “We will leave our graceless invalid to the ministrations of his sister and his nurse—indeed, we must! for Mrs. Priddy, having now a large stock of lint at her disposal, is about to descend upon him, armed with salves, compresses, and lotions, and you and I, my dear sir, will not be welcome here!”

Edward looked vexed, but as he could scarcely refuse to be dislodged there was nothing to be done but to take his leave. Nor did he receive any encouragement to stay from Venetia, who said frankly: “Yes, pray do go away, Edward! I know you mean it kindly, but I cannot have Aubrey put into a passion! He is not at all the thing yet, and Dr. Bentworth particularly charged me to keep him quiet.”

He began to say that he had not meant to put Aubrey in a passion; but the moralizing strain in him made it impossible for him to refrain from pointing out how wrong it was of Aubrey to fly into a rage only because one who had his interests sincerely to heart thought it his duty to reprove him. Before he was more than halfway through this speech, however, Venetia, seeing Aubrey raising himself painfully on his elbow, interrupted, saying hastily: “Yes, yes, but never mind! Just go away!”

She pushed him towards the door, which Damerel was holding open. He had intended to offer to escort her back to Undershaw, but before he could do so he had been irresistibly shepherded out of the room, and Damerel was shutting the door behind him, saying in a consolatory tone: “The boy is pretty well knocked-up, you know.”

“One can only hope it may be a lesson to him!”

“I daresay it will be.”

Edward gave a short laugh. “Ay! if one could but make him realize that he owes his aches to his own folly in persisting in his determination to ride horses he can’t control! For my part I consider it the height of imprudence in him to jump at all, for with that weak leg, you know—”

“But what a pudding-hearted creature he would be if he didn’t do so!” said Damerel. “Did you ever know a halfling who deemed prudence a virtue?”

“I should have supposed that when he knows what the consequences of a fall might be—However, it is always the same with him! he will never brook criticism—flies into a miff at the merest hint of it! I don’t envy you the charge of him!”

“Oh, I shan’t criticize him!” replied Damerel. “I have not the least right to do so, after all!”

Edward made no answer to this, merely saying, as he descended the stairs: “I do not know when Miss Lanyon means to return to Undershaw. I should be pleased to escort her, and had meant to have offered it.”

There was a decidedly peevish note in his voice. Damerel’s lips twitched, but he replied gravely: “I am afraid I don’t know either. Would you wish me to discover for you?”

“Oh, it is of no consequence, thank you! I daresay she won’t leave Aubrey until she has coaxed him out of his sullens—though it would be better for him if she did!”

“My dear sir, if you feel her groom to be an insufficient escort, do, I beg of you, make yourself at home here for as long as you choose!” said Damerel. “I would offer to go with her in your stead, but I might not be at hand, you know, and, I own, I should not have thought it at all necessary. However, if you feel—”

“No, no! it was merely—But if she has her groom there is of course no need for me to remain. Your lordship is very good, but I have a great deal of business to attend to, and have wasted too much of my time already.”

He then took formal leave, refusing all offers of refreshment, but expressing, in punctilious terms, his sense of obligation for the kindness shown to Aubrey, and his hope that it would soon be possible to relieve his lordship of so unwanted a burden.

To all of this Damerel listened politely, but with a disquieting twinkle in his eye. He said, in the careless way which had previously offended Edward: “Oh, Aubrey won’t worry me!” and having waved farewell almost before Edward’s foot was in the stirrup turned back into the house, and went up to Aubrey’s room again.

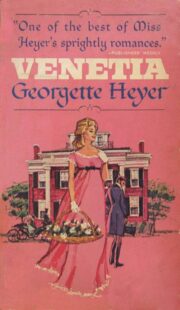

"Venetia" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Venetia". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Venetia" друзьям в соцсетях.