“Of course I did! I knew he wouldn’t care a rush for what Nurse said of him.”

“I expect he enjoyed it,” Venetia said, smiling. “When did he set out for Thirsk?”

“Oh, quite early! Now you put me in mind of it he gave me a message for you: something about being obliged to go to Thirsk, and hoping you’d pardon him. I forget! It was of no consequence: just doing the civil! I told him there was not the least need. He said he thought he should be back again by noon—oh, yes! and that he trusted you wouldn’t have gone away by then. Venetia, pray look on that table, and see if Tytler is there! Nurse must have moved it when she bandaged my ankle, for I had been reading it, and only laid it down when you came in. She can’t come near me without meddling! Essay on the Principles of Translation—yes,that’s it: thank you!”

“I think, if you should not object very much to my leaving you, that I’ll take a turn in the garden,” said Venetia, handing him the book, and watching him in some amusement as he found his place in it.

“Yes, do!” said Aubrey absently. “They will be plaguing me to eat a nuncheon soon, and I want to finish this.”

She laughed, and was about to leave him when a gentle tap on the door was followed by the entrance of Imber, announcing Mr. Yardley.

“What?” ejaculated Aubrey, in anything but a gratified tone.

Edward came in, treading cautiously, and wearing his most disapproving face. “Well, Aubrey!” he said heavily. “I am glad to see you looking stouter than I had expected.” He added, in a lower voice, as he clasped Venetia’s hand: “This is unfortunate indeed! I knew nothing of what had happened until Ribble told me of it half-an-hour ago! I was never more shocked in my life!”

“Shocked because I took a toss?” said Aubrey. “Lord, Edward, don’t be such a slow-top!”

Edward’s countenance did not relax; rather it seemed to grow more rigid. He had not exaggerated his state of mind; he was profoundly shocked. He had ridden to Undershaw in happy ignorance, to be met with the alarming tidings that Aubrey had had a bad accident, which had made him instantly fear the worst; and hardly had Ribble reassured him on this head than he was stunned by the further news that Aubrey was lying under Damerel’s roof, with not only Nurse in attendance on him but his sister also. The impropriety of such an arrangement really appalled him; and even when he was made to understand that Venetia was not sleeping at the Priory he could not forbear the thought that any disaster (short of Aubrey’s death, perhaps) would have been less harmful than the chance that had pitchforked her into the company of a libertine whose way of life had for years scandalized the North Riding. The evils of her situation were, in Edward’s view, incalculable; and foremost amongst them was the probability that such a man as Damerel would mistake the inexperience which led her to behave so rashly for the boldness of a born Cytherean, and offer her an intolerable insult.

A level-headed man, Edward did not suppose that Damerel was either so foolhardy or so steeped in villainy as to attempt the seduction of a girl of virtue and quality; but he was very much afraid that Venetia’s open, confiding manners, which he had always deplored, might encourage him to believe that she would welcome his advances; while the peculiar circumstances under which she lived would certainly lead him to think that she had no other protector than a crippled schoolboy.

Edward saw his duty clear; he saw too that the performance of it was more than likely to involve him in consequences repugnant to a man of taste and sensibility; but he did not shrink from it: he set his jaw, and rode off to the Priory, not in such a spirit of knight-errantry as Oswald Denny would have brought to the task, but inspired by a sober man’s determination to protect the reputation of the lady whom he had chosen to be his bride. At the best, he hoped to bring her to a sense of her impropriety; at the worst, he must bring Damerel to a precise understanding of Venetia’s true circumstances. This task could not be other than distasteful to one who prided himself on his correct and well-regulated life; and it might, if Damerel were as careless of public opinion as he was said to be, plunge him into just the sort of scandal his disposition urged him to avoid. He was by no means deficient in courage, but he had not the smallest wish, whatever Damerel’s offences might be, to find himself confronting his lordship early one morning with a pistol in his hand and twenty yards of cold earth between them. If it came to that it would be because Aubrey’s recklessness and Venetia’s incorrigible imprudence had forced him into a position from which, as a man of honour, he could not draw back, even when he considered her to have courted whatever ill might befall her by stepping beyond the barriers of strict propriety, and so giving such men as Damerel a false notion of her character.

It was therefore not with romantic ardour that he rode from Undershaw to the Priory but with a sense of outrage and an exacerbated temper rather hardened than mollified by being kept under rigid control.

His arrival almost coincided with that of Damerel, from Thirsk. As he dismounted, Damerel came striding round the corner of the house from the stables, a package tucked, with his riding-whip, under one arm while he pulled off his gloves. At sight of Edward he checked, in surprise, and for a few moments they stood looking one another over in silence, hard suspicion in one pair of eyes, and in the other a gathering amusement. Then Damerel lifted an enquiring eyebrow, and Edward said stiffly: “Lord Damerel, I believe?”

They were the only rehearsed words he was destined to utter. From then on the meeting proceeded on lines quite unlike any for which he had prepared himself. Damerel strolled forward, saying: “Yes, I’m Damerel, but you have the advantage of me, I fear. I can guess that you must be a friend of young Lanyon’s, however. How do you do?”

He smiled as he spoke, and held out his hand. Edward was obliged to shake hands with him, a friendly gesture which forced him to abandon the formality he had decided to adopt.

“How do you do?” he responded, with civility, if not with warmth. “Your lordship has guessed correctly: I am a friend of Aubrey Lanyon—I may say a lifelong friend of his family! I cannot suppose that my name is known to you, but it is Yardley—Edward Yardley of Netherfold.”

He was mistaken. After a frowning moment Damerel’s brow cleared, he said: “Does your land lie some few miles beyond my south-western boundary? Yes, I thought so.” He added, with his swift smile: “I flatter myself I am making progress in my knowledge of the neighbourhood! Have you been visiting Aubrey?”

“I have only this instant arrived, my lord—from Undershaw, where I was informed by the butler of this very unfortunate accident—He told me also that Miss Lanyon was here.”

“Is she?” said Damerel indifferently. “I’ve been out all the morning, but it’s very probable. If she’s here she will be with her brother: do you care to go up?”

“Thank you!” Edward said, with a slight bow. “I should like to do so, if Aubrey is sufficiently well to receive a visitor.”

“I daresay it won’t do him any harm,” replied Damerel, leading the way through the open door into the house. “He’s not much hurt, you know: no bones broken! I sent for his doctor to come to him last night, but I don’t think I should have done so if he hadn’t told me that he had a diseased hip-joint. He is none too comfortable, but Bentworth seems to be satisfied that if only he can be kept quiet for a time no evil consequences need be anticipated. Once he had discovered the existence of my library I saw that there would not be the least difficulty about that.”

There was a laugh in his voice; none at all in Edward’s as he answered: “He always has his head in a book.”

Damerel had moved to where a frayed bell-pull hung beside the stone fireplace; as he tugged at it he shot a swift, appraising glance at Edward. The gleam of amusement in his eyes was pronounced, but he said only: “You, I apprehend, are too well-acquainted with him to be astonished by the scope and power of his quite remarkable intelligence. I, on the other hand, after sitting with him for some hours last night, my forgetful and, alas! indolent brain at full stretch to bear me up through arguments which ranged from disputed texts to percipient mind, retired from the lists persuaded that what threatened the boy was not a crippled leg but an addled brain!”

“Do you think him so clever?” asked Edward, rather surprised. “For my part I have often thought him lacking even in commonsense. But I myself am not at all bookish.”

“Oh, I shouldn’t think he has any commonsense at all!” returned Damerel.

“I confess I consider it a pity he had not enough to refrain from riding a horse he could not master,” said Edward, with a slight smile. “I warned him how it would be when I first set eyes on that chestnut. Indeed, I begged him most earnestly not to make the attempt.”

“Did you?” said Damerel appreciatively. “And he didn’t heed you? You astonish me!”

“He has been very much indulged. That, of course, was made inevitable, to some degree, by his sickliness; but he has been allowed to have his own way beyond what is proper, from the circumstances attached to his upbringing,” said Edward, painstakingly explaining the Lanyons. “His father, the late Sir Francis Lanyon, though in many respects a most estimable man, was eccentric.”

“So Miss Lanyon informed me. I should suppose him to have been a curst rum touch, myself, but we won’t quarrel over terms!”

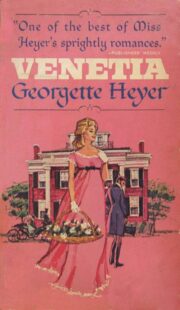

"Venetia" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Venetia". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Venetia" друзьям в соцсетях.