“To laugh with!” he repeated slowly.

“Perhaps you have friends already who laugh when you do,” she said diffidently. “I haven’t, and it’s important, I think—more important than sympathy in affliction, which you might easily find in someone you positively disliked.”

“But to share a sense of the ridiculous prohibits dislike—yes, that’s true. And rare! My God, how rare! Do they stare at you, our worthy neighbours, when you laugh?”

“Yes! or ask me what I mean when I’m joking!” She glanced at the clock above the empty fireplace. “I must go.”

“Yes, you must go. I have sent a message down to the stables. There is still light enough for your coachman to make out the way, but it will be dark in another hour, or even less.” He took her hands, and putting them palm to palm held them so between his own. “You’ll come again tomorrow—to visit Aubrey! Don’t let them dissuade you, our worthy neighbours! Beyond my gates I make you no promises: don’t trust me! Within them—” He paused, his smile twisting into something not quite a sneer yet derisive. “Oh, within them,” he said in brittle self-mockery, “I’ll remember that I was bred a gentleman!”

V

Venetia opened her eyes to sunlight, dimmed by the chintz blinds across her windows. She lay for a few minutes between sleep and waking, aware, at first vaguely and then with sharpening intensity, of a sense of well-being and of expectation, as when, in childhood, she had waked to the knowledge that the day of a promised treat had dawned. Somewhere in the garden a thrush was singing, the joyous sweetness of its note so much in harmony with her mood that it seemed a part of her happiness. She was content for some moments to listen, not questioning the source of their happiness; but presently she came to full consciousness, and remembered that she had found a friend.

At once the blood seemed to quicken in her veins; her body felt light and urgent; and a strange excitement, flooding her whole being like an elixir, made it impossible for her to be still. No sound but bird-song came to her ears; quiet enfolded the house. She thought it must be very early, and, turning her head on the pillow, tried to recapture sleep. It eluded her; the sunlight, blotched by the pattern on the chintz, teased her eyelids: she lifted them, yielding to a prompting more insistent than that of reason. A new day, fresh with new promise, set her tingling; the thrush’s trill became a lure and a command; she slid from the smothering softness of her feather-bed, and went with a swift, springing step to the window, sweeping back the blinds, and thrusting open the casement.

A cock pheasant, pacing across the lawn, froze into an instant’s immobility, his head high on the end of his shimmering neck, and then, as though he knew himself safe for yet a few weeks, resumed his stately progress. The autumn mist was lifting from the hollows; heavy dew sparkled on the grass; and, above, the sky was hazy with lingering vapour. There was a chill in the air which made the flesh shudder even in the sun’s warmth, but it was going to be another hot day, with no hint of rain, and not enough wind to bring the turning leaves fluttering down from the trees.

Beyond the park, across the lane that skirted Undershaw to the east, beyond its own spreading plantations, lay the Priory: not very far as the crow flew, but a five-mile drive by road. Venetia thought of Aubrey, whether he had slept during the night, whether there were many hours to while away before she could set forth to visit him. Then she knew that it was not anxiety for Aubrey, her first concern for so many years, which made her impatient to reach the Priory, but the desire to be with her friend. It was his image, ousting Aubrey’s from her mind’s sight, which brought such a glow of warmth to her. She wondered if he too was conscious of it; if he was wakeful, perhaps looking out of his window, as she from hers; thinking about her; hoping that she would soon be with him again. She tried to remember what they had talked of, but she could not; she remembered only that she had felt perfectly at home, as though she had known him all her life. It seemed impossible that he should not have felt as strongly as she the tug of sympathy between them; but when she had thought for a little she recalled how widely different were their circumstances, and recognized that what to her had been a new experience might well have meant nothing more to him than a variation on an old theme. He had had many loves; perhaps he had many friends too, with minds more closely attuned to his than she believed her own to be. These troubled her as his loves did not. With his loves she was as little concerned as with his first encounter with herself. That had angered her, but it had neither shocked nor disgusted her. Men—witness all the histories!— were subject to sudden lusts and violences, affairs that seemed strangely divorced from heart or head, and often more strangely still from what were surely their true characters. For them chastity was not a prime virtue: she remembered her amazement when she had discovered that so correct a gentleman and kind a husband as Sir John Denny had not always been faithful to his lady. Had Lady Denny cared? A little, perhaps, but she had not allowed it to blight her marriage. “Men, my love, are different from us,” she had said once, “even the best of them! I tell you this because I hold it to be very wrong to rear girls in the belief that the face men show to the females they respect is their only one. I daresay, if we were to see them watching some horrid, vulgar prize-fight, or in company with women of a certain class, we shouldn’t recognize our own husbands and brothers. I am very sure we should think them disgusting! Which, in some ways, they are, only it would be unjust to blame them for what they can’t help. One ought rather to be thankful that any affairs they may have amongst what they call the muslin company don’t change their true affection in the least. Indeed, I fancy affection plays no part in such adventures. So odd!—for we, you know, could scarcely indulge in them with no more effect on our lives than if we had been choosing a new hat. But so it is with men! Which is why it has been most truly said that while your husband continues to show you tenderness you have no cause for complaint, and would be a zany to fall into despair only because of what to him was a mere peccadillo. ‘Never seek to pry into what does not concern you, but rather look in the opposite direction!’ was what my dear mother told me, and very good advice I have found it. She spoke, of course, of gentlemen of character and breeding, as I do now—for with the demi-beaux and the loose-screws females of our order, I am glad to say, have nothing to do: they do not come in our way.”

But Damerel had come in their way, and although he was not a demi-beau he was certainly a loose-screw. Lady Denny had been obliged to receive him with the appearance at least of complaisance, but she was not going to pursue so undesirable an acquaintance; and there could be little doubt that she would be horrified when she discovered that her young protegee was not only on the best of terms with him but was also committing the gross impropriety of visiting his house. Could she be made to understand that he, like those nameless, aberrant husbands, had two sides to his character? Venetia thought not. The best to be hoped was that she would understand that while Aubrey lay at the Priory his sister would go to him though Damerel were a Caliban.

The clatter of shutters being folded back in the parlour beneath her room roused her from these doubtful reflections. If the servants were stirring it was not so very early after all: probably about six o’clock. Seeking an excuse for rising an hour before her usual time she remembered the several not very pressing duties which had been left undone on the previous day, and decided to perform them immediately.

She was no bustling housewife, but by the time she came into the breakfast-parlour she had visited the dairy and the stables; discussed winter-sowing with the bailiff; delivered to the poultry-woman, in a slightly expurgated form, a remonstrance from Mrs. Gurnard; listened in return to a Jeremiad on the general and particular perversity of hens; and directed an aged and obstinate gardener to tie up the dahlias. It seemed improbable that he would do so, for he regarded them as upstarts and intruders, which in his young days had never been heard of, and always became distressingly deaf whenever Venetia mentioned them.

Mrs. Gurnard, to Venetia’s relief, took it for granted that she would drive over to see poor Master Aubrey, but was thrown into dignified sulks by Venetia’s refusal to carry with her a sizeable hamper packed as full as it would hold with enough cooked food for a banquet. When asked, in a rallying tone, if she supposed Aubrey to be living on a desert island she replied that there were many who would consider him to be better off on a desert island than abandoned to the rigours of Mrs. Imber’s cookery. Mrs. Imber, said Mrs. Gurnard, besides being feckless, inching, and unhandy, was one whom she could never bring herself to trust. “I’ve not forgotten the pullets, miss, if you have, and what’s more I never shall, not if I live to be a hundred!”

“Pullets?” said Venetia, bewildered.

“Cockerels!” uttered Mrs. Gurnard, her eyes kindling. “Cockerels every one, miss!”

But as Venetia could perceive no connection between cockerels and Mrs. Imber’s cookery she remained adamant, and went off to collect the various items which Nurse, in the agitation of the moment, had omitted to pack. These included the shirt she was making for Aubrey, and her tatting, both to be found in her sewing-basket, together with needles, thread, scissors, her silver thimble, and a lump of wax. Venetia was to wrap all these things up neatly in a napkin, and to be sure not to forget any of them; but as Venetia knew that the only certainty was of being told that she had brought the wrong thread and the very scissors Nurse had not wanted she preferred, in spite of its formidable dimensions, to take the basket itself to the Priory.

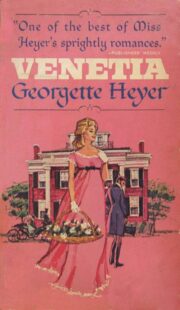

"Venetia" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Venetia". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Venetia" друзьям в соцсетях.