Logan stood, his back to the closed door, breathing slowly. Deeply. Her mouth had been far sweeter than he had remembered. The sensation of her full breasts against his chest had made his senses reel and his manhood ache with his need. The boldness of the words he had just spoken to her burned in his throat. Instinct had warned him it was too soon, but how he had wanted her in his bed this night. Tom’s advice had been good, but he could not play this game with her forever. He had not the patience for it, he knew. He loved her too much. Logan wanted Rosamund as his wife. And his wife she was going to be sooner than later. He slept badly. As did Rosamund.

Her dreams were wild, jumbled impressions that left her tossing and restless and more awake than asleep. She awoke bleary-eyed and irritable, but she was ready to begin preparing the trap they had devised the previous evening to rid Friarsgate of her cousin Henry Bolton once and for all. For all of her life she had been troubled, first by her father’s youngest brother and now by his son. Her uncle’s bones rested in the family burial ground. But Rosamund knew she would not feel safe until her cousin lay beside his father.

To her surprise, she found Logan gone when she came down into the hall. He had, a servant informed her, departed at first light with just a few of his clansmen. Then her uncle Edmund entered the hall.

“You are awake at last, niece!” he said jovially. “Logan has left me instructions for our part in this charade. We must begin today, for the sooner this is over and done with, the better for Friarsgate. I do not relish a winter defending ourselves from not just four-legged wolves, but two-legged ones, as well.”

“He might have said good-bye,” Rosamund said, annoyed.

“I thought you might have said farewell to each other last night,” Edmund murmured innocently.

She threw him an evil look. “I showed him to his chamber and went to my own,” she said. “I assumed he would be here when I returned to the hall and would speak with me himself instead of giving instructions to you, uncle.” She felt her anger beginning to rise, and then the oddest thing happened. She remembered her anger of the previous evening and how he had calmed her. She could almost feel his lips on hers now, and as she did, the anger began to drain away. “He was wise to leave early,” she said suddenly, surprising Edmund. “We must be scrupulous in our execution of this plan, or we will fail miserably. What would the laird have us do, uncle?”

“We must prepare the false gold and transport it in secret to the abbey near Lochmaben. And we must do it without your cousin’s men observing us. To that end, the laird’s men are scouring the few caves in our hillsides where an intruder might secrete himself to spy on us. Others of the Hepburns are posted upon our heights. But we must work quickly, Rosamund, for we do not want to arouse Henry the younger’s suspicions.”

“Have the bricks brought into the house through the kitchen garden door,” she said. “Not all at once, but a few at a time over the day. We cannot be certain we are not being watched, and I would not have anyone’s curiosity aroused by a constant stream of men and women going in and out of the house. At twilight and in the darkness of the evening the rest of the bricks may be carried inside.”

“Where do you want them?” he asked.

“In the hall,” Rosamund said. “We will wrap them here.”

The morning meal was brought and eaten. People came and went throughout the day while Rosamund, Philippa, Maybel, and several of the servingwomen carefully wrapped each brick in a natural-colored felt fabric and then tied the wrappings with wool twine so the contents remained well concealed. The pile of wrapped bricks never grew any larger, for as each brick was covered with felt and tied, it was removed from the hall. Finally all the bricks were wrapped and gone from the hall. They had been taken over the long day and early evening to a barn, where they were loaded in a covered wooden wagon that would be transported first over the border to Claven’s Carn and from there to the deserted abbey where the wagon’s cover would then be removed. A tarpaulin would replace it, being tied down for effect. But the transport would remain in Rosamund’s barn until the laird returned and gave the word it was to be moved.

And he did return several days later. “Twenty of my men are now populating the abbey,” he said. “We will transport our gold over the border tomorrow and from there to Lochmaben. When I return again we will be ready to inform Lord Dacre and Henry the younger of the gold they may steal.” He laughed. “You have done your part well, Rosamund. The bricks make quite a convincing shipment of gold.”

“Aye, we worked hard to be certain there is not the faintest sign of what is really between those wrappings,” she told him.

“In two days Tom will seek out Lord Dacre, and Edmund, Henry the younger. I know where both are now located. Leaving at the same time, they should reach their quarry at approximately the same time. The trick will be to return to us at the same time with the news that they have both taken the bait.”

Two days later Edmund, six men-at-arms with him, rode to where his nephew hid himself between his border forays. Henry the younger was surprised to see his uncle, but he greeted him cordially enough. Edmund did not dismount his horse.

“This is not a social call, nephew,” he said bluntly.

Henry felt at somewhat of a disadvantage standing by his uncle’s mount. “Get down, Edmund Bolton, so we may speak eye to eye,” he said. “Come in and have some wine. I have an excellent keg I relieved a traveling merchant of recently.” And he chuckled as if it were all a jest.

But Edmund remained atop his mount. “Nay. There is something I have come to say, Henry,” he told his nephew. “I want you to cease harassing Friarsgate. I want you to put all thoughts of marrying Philippa Meredith from your head. A match is being arranged for her with the second son of an earl. It is what the family wants. However, in return for your cooperation, we are willing to direct you to a rather large cache of gold, yours for the taking, nephew. Easy pickings, unless, of course, you are afraid of a band of Scottish monks,” he said scornfully. “You have no real love for Friarsgate. Would you not be content instead with gold?”

“Perhaps,” Henry said softly. “Tell me more, uncle.”

“Your word first that you will cease seeking to kidnap little Philippa. She is yet a child, Henry, and would be more troublesome than useful to you. And you could not keep her from her mother for long. Rosamund is a strong-willed woman, as your father learned.”

“Rosamund should have been my wife,” Henry the younger said. “It could be my son who inherited Friarsgate, and not another girl, uncle.”

Edmund’s laughter was brittle. “What are you now, nephew? Seventeen? Rosamund is twenty-five, and she would kill you before she would marry you. You do not want Friarsgate, lad. That was your father’s dream, and where did it get him but a narrow plot in the family’s burial ground? His lust for what was not his drove your mother away. It turned her from a vapid but decent girl into… well, lad, you know what Mavis became. And you? You are hunted and will be one day caught and hung.” He paused for a long moment. “Unless you decide to change your fate, Henry. Give me your word that you will leave the Boltons of Friarsgate alone, and I will make you rich, so rich you may leave here and begin your life anew. You were not meant to be a bandit in the borders, nephew. Do you really want your mother to come upon you one day, hanging at the side of the road? Would you break her heart that way? With the gold I offer you, you can rescue her from her shame and let her live out her life peaceably.”

For a brief moment Henry the younger’s face softened. Then his eyes narrowed, and he said, “Tell me!”

“Your promise first,” Edmund replied.

“You would accept my word?” Henry the younger sounded surprised, but he was also flattered. No one had ever agreed to accept his word before. “You have my hand on it, uncle. If you will tell me where this gold is, and if I can obtain it, I will leave Friarsgate and its inhabitants in peace. I will go south, as Thomas Bolton’s antecedent did. Perhaps I will have the same good fortune as he did.” That is not to say I will not return one day, Henry the younger thought silently. But Friarsgate was not for him, and he knew it. Besides, he hated the stink of sheep.

Edmund took his nephew’s hand and shook it. “The gold is at an abbey in the borders near Lochmaben. I learned of its existence from a Hepburn clansman. The laird’s cousin, the now-deceased Earl of Bothwell, had stored it there for King James before the war. Now it is needed to support the little king, and the queen regent has sent for it to be brought to Stirling. There is but one place where it may be safely taken, nephew. The vehicle bearing the gold will travel from the abbey down to the Edinburgh road. It is a distance of but a few miles. Midway between the abbey and that junction in the road is the ideal place to snatch it. The wagon will be driven by two monks. It is hoped such an equipage will not attract any attention,” Edmund said.

“You have remarkably good information, uncle,” Henry the younger said suspiciously.

“Of course I do,” Edmund agreed. “We hired out Hepburn clansmen to watch over Friarsgate. We pay them, and house and feed them. We are borderers no matter which allegiance we espouse when our kings go to war, nephew. The Scots have become comfortable with us, and they talk a great deal, for they are lonely for their families. They are also proud of their family connections, and the Earl of Bothwell, Patrick Hepburn, was responsible for hiding this gold at Lochmaben. I am sure that if Lord Dacre learns of this transport of gold he will want it, too. But that is unlikely, nephew. So there it is for the taking, if you are not afraid.”

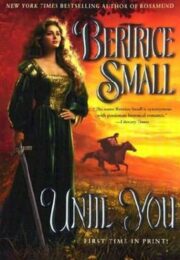

"Until You" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Until You". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Until You" друзьям в соцсетях.