“And who is Cecily?” Rosamund inquired, smoothing her daughter’s disheveled hair. “Is she someone Uncle Tom has introduced you to, my daughter?”

“She is Cecily FitzHugh, mama. Her father is the Earl of Renfrew. She has two brothers, Henry, who is the heir, and Giles, and two sisters, Mary and Susanna. They are younger than Cecily, who is the oldest girl. We have become best friends!”

“Gracious,” Rosamund laughed. “All in a single afternoon, poppet?”

Philippa ignored her mother’s teasing, saying, “It is her first time at court, too, mama. She has been left at home with her little sisters in the past. Her brother Henry is one of the king’s gentlemen, and her other brother is a page. We both like to ride.”

“Well,” Rosamund said, “it would appear that you have had a fine day, Philippa, but it is your bedtime now. Run along with Lucy. I will come and kiss you good night.”

Without protest, Philippa obeyed her mother.

“And what have you been doing alone and by yourself?” Lord Cambridge asked his cousin.

“I have been thinking of Logan Hepburn, Tom, and whether I do indeed want to remarry. And if so, whether it is he I want to wed,” Rosamund said frankly.

“And what have you decided?” he asked.

“I do not know,” she answered. “I need to really get to know him, Tom. I will not remarry simply for the sake of having a husband. Do you understand that?”

He nodded. “I do. Still, I think you wise to reconsider your former position on the matter, cousin.”

“What you mean,” she teased him, “is that you think I am becoming too long in the tooth for another husband. I am, after all, twenty-five now.”

He laughed. “You will never be too old for another husband, Rosamund. You are too fair and too clever by far. Why, if I were a man to take a wife, I should seriously consider you above all women,” he told her.

“Why, Tom, that is a lovely thing for you to say to me,” she exclaimed.

“Alas, I am not a man for a wife,” he told her with a smile.

“It would be so simple if you were,” she considered.

“It most certainly would not, dear girl! Your laird once threatened to kill me if I admitted to being your lover,” Lord Cambridge said with a shiver of remembrance. “He was very fierce, and I quite believed him.”

Now it was Rosamund who laughed. Then she said, “Tell me about the FitzHugh family to whom you have introduced my daughter, Tom.”

They sat companionably in the Great Hall of the house, ensconced in the window seats overlooking the river as they spoke.

“Edward FitzHugh is like your Owein, of Welsh descent. His holding is not large. It is in the marches between England and Wales. His wife, Anne, comes from a good family of English landed gentry in Hereford. Her dower was more than generous, for her family was delighted to have made a match with the son of an earl. Ned was the third son. He was never expected to inherit, but both of his brothers predeceased him. The eldest from plague one summer. The second son returning from Spain, where he had made a match. The ship upon which he traveled went down in the Bay of Biscay in a storm. The old earl died shortly thereafter, they say of a broken heart, and his third son inherited. Ned had been educated for a time with the king, for it was thought he might take holy orders one day. When he became the Earl of Renfrew, he used that ancient connection to bring his family to court. His lamented second brother had been betrothed to a distant cousin of Queen Katherine’s. The family is also devout, so the queen favors them. It is said that little Cecily will eventually be offered a place in the queen’s household as a maid of honor. She is too young now, of course, but if she and Philippa remain friends, your daughter might also serve as one of the queen’s maids of honor one day.”

“Thomas Bolton, you are amazing!” Rosamund said admiringly. “How on earth do you know all of this? I do believe you have surpassed yourself this time with your intimate knowledge of others.”

“Nonsense, dear girl,” he said, delighted with her words. “The Countess of Renfrew’s father knew my grandfather in London eons ago. They had some dealings that turned out well for both of them, but especially for the countess’ papa. The connection has been kept. I was even invited to the earl’s wedding to his wife years ago, when he was simply a third son. I was generous in my gifts. After all, dear girl, one never knows.”

“You are thinking of the second son for Philippa, aren’t you?” Rosamund said.

Lord Cambridge nodded. “Giles FitzHugh is fourteen now. He is still involved in his studies, and he is serving the queen. He will soon be too big for her household, Ned tells me, and will not return to court in the autumn. He will be sent to France and then to Italy to study. His brother is sixteen and has served the king since he was six. He will be married in August to a Welsh heiress. Giles, for all his half-noble bloodlines, has a bent towards business. Philippa will need a husband who understands such things.”

“What if his brother dies?” Rosamund asked.

“Is that likely to happen again?” Tom said. “Besides, the heir’s bride is already with child. Both fathers wanted it that way.”

Rosamund was somewhat shocked. “I should certainly not allow my daughters-” she began, but he waved away her indignation.

“This was a unique case, dear girl. Ned wanted to be certain that his eldest son’s heir followed them. The bride’s father wanted the title for his daughter. Both the young people, healthy and lusty, were content to comply with their parental demands,” he chuckled with a wink.

“It could be a girl,” Rosamund said dryly.

“It could,” Tom agreed cheerfully. “Both FitzHugh sons, however, are, praise God, healthy. The heir will continue to get children on his bride until there is a son or two, perhaps even three.”

“What if Philippa and this boy do not get along?” Rosamund asked.

“They have not even met yet, dear girl. That will happen at Windsor. But our lass is only ten, and the boy is not ready, by any means, for a betrothal. This is merely a small fishing expedition at best. I know other families with eligible sons.”

Rosamund nodded. “But after Windsor, I want to go home. I have some business of my own to take care of, Tom. And before we depart London we must meet with your goldsmiths and choose a factor for our little venture.”

“Agreed!” he said. “Tomorrow, after we deposit Philippa with her new friend, we shall complete our own business, dear girl. And when I get home I must go to Leith to see how our ship is coming along. I should like to call this first vessel after you, cousin.”

“I think I have a better name than mine, dearest Tom,” she told him. “I think we should call our ship Bold Venture, for it is indeed a bold venture that you and I undertake.”

He nodded. “Aye, I like it. Bold Venture. Aye!” he agreed.

The following morning they took Philippa to court, leaving her with Lucy to find Cecily FitzHugh. They then went on to Goldsmiths’ Row, where the banking of the day was conducted. Lord Cambridge introduced his cousin to Master Jacobs, his goldsmith. Rosamund put her signature upon a piece of parchment several times so the goldsmith would have it to compare with any message purporting to come from her. Lord Cambridge had brought Master Jacobs a copy of his last will and testament for safekeeping and so that the goldsmith would know that Rosamund and her daughters were his heirs. He brought the agreement they had both signed for their enterprise, giving the goldsmith a copy of it, too.

“My cousin and I will both be depositing funds and withdrawing them, Master Jacobs,” he told the goldsmith. “Lady Rosamund is a large landowner in Cumbria, where I now make my home.”

“What will you use the ship for, my lord?” the goldsmith asked.

“We will export my cousin’s woolen cloth to Europe. There is none finer, and the Friarsgate Blue will be the most sought after,” Tom explained.

“What will your ship return with in exchange?” the goldsmith inquired.

“Tom!” Rosamund said. “We have not considered another kind of cargo. We cannot have our vessel returning with an empty hole. There is but half-profit in that.”

“I have relations in both Holland and the Baltic, my lord, my lady. For a small percentage of your profits, they could fill your ship for its return journey,” Master Jacobs said.

“It can be nothing that stinks,” Rosamund said. “We would never get the smell out of the wood of the hole. The next shipment of cloth would pick up the aroma. No hides or cheeses. Wine. Wood. Pottery. Gold. But nothing that would leave a noxious fragrance. My captain will have such orders, Master Jacobs. He will take no cargo that smells.”

“Of course, my lady. Now I comprehend your need for a new vessel. The fee I suggest is fifteen percent,” he told her, smiling. “It is a modest fee.”

Rosamund shook her head. “Nay,” she said in a hard voice. “It is too much.”

“Twelve,” he countered, and seeing the look in her eye quickly said, “Ten is the lowest I can go, my lady.” His mouth puckered nervously.

“Eight percent and not a penny more, Master Jacobs. I am being generous with you for the sake of your long-standing arrangement with my cousin. We have built the ship, grown the wool, and woven the cloth. The risk is all ours. Eight percent for bringing in return cargo is more than fair.”

The goldsmith’s pursed lips turned up into a smile. “Agreed, my lady!” he said. Then he turned to Lord Cambridge. “She both bargains and reasons well, old friend.”

“Indeed she does,” Tom said proudly.

“What are we to do about a factor?” Rosamund asked him when they were once more in their barge on the river.

“I think there is time for that,” Lord Cambridge said thoughtfully. “Perhaps we need not find someone on this visit to London. My instincts tell me to wait.”

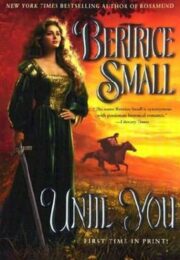

"Until You" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Until You". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Until You" друзьям в соцсетях.