“He could remember,” Adam insisted.

She smiled sadly. “How like your father you are,” she told him. Then she rose from her place and left him alone in the hall.

The morning came. Once again they gathered in the hall to break their fast. And afterwards both parties found themselves ready to depart. It was an awkward moment. Finally Rosamund walked over to the Leslies. She held out her hand to Adam, who kissed it.

The earl gave Rosamund a brief smile. “I thank you for your care of me, madame,” he said, as he, too, kissed her gloved hand.

Reaching up, she touched Patrick’s handsome face. “Farewell, my love,” she whispered, her eyes scanning his face a final time for something. Anything. There was nothing. Rosamund’s hand fell to her side, and she turned and walked through the front door to where her horse was waiting, mounting it without assistance. She heard Tom and Philippa behind her offering their good-byes. They joined her finally, and their party moved off down the lane and into the High Street.

Adam Leslie watched them go. Watched as they turned into the High Street. “You remember nothing, father? Nothing?”

“Nothing,” Patrick Leslie, Earl of Glenkirk said. “I wish I did, for she is lovely, but I do not. I should have been cheating her had I pretended otherwise.” Then he walked from the house and mounted his horse. “Let us go home, Adam. It seems I have been away from Glenkirk forever.”

Tom had hired two dozen men-at-arms to escort them home. Once on the road, Rosamund became more visibly anxious to reach Friarsgate. The first day she forced the pace, refusing to stop until the sun had set and the land was enshrouded in twilight. She had passed the comfortable inn Tom had meant them to stay in, and now they bedded down in a farmer’s barn with no supper.

“You cannot treat the men this way,” he told her half-angrily.

“I must get home,” she insisted. “I will die now if I do not get home!”

“Philippa should not be sleeping in a hayloft, Rosamund,” he said. “And we have had nothing to eat, dammit!”

“Give the farmer’s wife something, and she will feed you,” Rosamund replied.

Tom swore a long string of rather colorful oaths beneath his breath.

Rosamund laughed. “Why, cousin,” she said, “I did not think you knew such wicked language.” The laugh had been hard.

In the morning Tom paid the farmer’s wife more coin than she had ever seen to feed them all. She willingly complied, though the fare was simple. Rosamund barely ate at all, and she demanded that they all hurry.

“We have a long day’s ride ahead of us,” she said, and she mounted her animal and rode off ahead of them.

Without being told, two of the men-at-arms leapt upon their own mounts and hurried after her while the rest of them finished their meal before departing.

“What the hell is the matter with her?” Tom asked Maybel as they rode.

“Friarsgate is where she gains her strength,” Maybel answered. “Her strength is almost gone with her anguish. She will ride her horse into the ground to reach home before her will dies on her.”

“Neither Philippa nor Lucy nor you can keep such a pace,” he said.

“I will do what I have to. Philippa and Lucy are young. We will all survive just knowing that Friarsgate is awaiting us,” Maybel told him.

They rode on. At the noon hour he insisted that they stop at a comfortable inn, to rest the horses, he told her. Then he ordered a large meal for them all, including the men-at-arms, for he knew she would ride until they could no longer see the track ahead of them. He also knew that they were approaching the border.

“We can stay the night at Claven’s Carn,” he told Rosamund.

She looked coldly at him. “No,” she said. “I will not stop at Claven’s Carn.”

“Then break our journey here today. You almost rode us into the ground yesterday,” Tom pleaded.

“No,” she said again. “We can get past Claven’s Carn, and then by noon tomorrow we will reach Friarsgate, Tom.”

“There is no place between Friarsgate and Claven’s Carn where we may stay!” he shouted at her.

“We can bed down in a field,” she replied.

“You would ask Maybel, Lucy, and Philippa to sleep in a pasture?” His face was flushed with his anger.

“If you hadn’t made us stop to indulge everyone with food and drink we might have gotten even closer to home today,” Rosamund said, ignoring his outburst.

“You have gone mad!” he accused her.

“I want to go home, Tom! What the hell is the matter with that?”

“Nothing! As long as you don’t kill us all getting there, Rosamund! We will stay at Claven’s Carn tonight, and that is final!”

“You may stay at Claven’s Carn. I will not,” she told him implacably.

The day, which had begun fair, now clouded up with typical springlike contrariness. By sunset, a light rain was falling, and Claven’s Carn loomed ahead, its two towers piercing the graying twilit sky.

“Ahead is where we will overnight,” Tom told the captain of his men-at-arms. “Send a man ahead to beg shelter for the lady of Friarsgate before they close the gates.”

“Yes, my lord!” the captain said, signaling to one of his men to go.

“The laird will not refuse us hospitality,” Tom murmured to Maybel.

“Nay, nor will his wife,” Maybel said. “But I warn you now that your cousin will fight you in this matter. I have known Rosamund all her life, and when she sets her mind to something, nothing will prevent her from enacting her will. Still, I have never seen her quite like this before. I think if there were a border moon she would travel on this night.”

“The horses will not stand the pace,” he said.

“Then try and reason with her,” Maybel told him.

Tom spurred his mount ahead in order to ride apace with his cousin. “Rosamund, be reasonable, I beg of you,” he began.

She stared straight ahead.

“If you will not have mercy on those who travel with you, consider the horses. They cannot be ridden without rest.”

“We can rest when we are past Claven’s Carn and over the border,” she said stonily. “It is not dark yet, Tom. We can make several more miles before the darkness sets in and obscures the track.”

He grit his teeth, struggling to maintain an even tone with her. “I should not disagree if the weather would cooperate, but with every moment the rain grows heavier. It will be one of those all-night spring rains, cousin. You cannot ask Maybel, Lucy, and your daughter to ride through the night in the pouring rain. And again, I beg you to consider the animals. How will we see the road when the darkness falls? There is no moon on a rainy night. If we do not shelter at Claven’s Carn, we will be forced to spend the night out in this weather. If any of us catches an ague, it could kill us.”

“We will have men with torches light the path for us,” she said implacably.

“I know you mourn, Rosamund,” he began, but she waved him away.

“Stop at Claven’s Carn if you must, Tom, but I have to go on,” she told him.

“What does it matter if we stop?” he demanded, his voice now showing his anger and impatience with her. “We will still not reach Friarsgate until tomorrow.”

“I will reach it earlier if I travel farther today.”

“You have truly gone mad!” he said, and after turning his horse about, he rode back to where Maybel plodded along in the line.

“She says we may stop, but she will go on,” he reported. His face was red with his frustration.

Maybel could not help but laugh. “Do not trouble yourself over it, my lord. Let her believe she is going on tonight. We will ask the lord of the keep to ride after her and convince her to return and seek shelter. He will do it. He has never stopped loving her, despite his good wife.”

“She hates Logan Hepburn!” Tom exclaimed. “If he said come, she would go. If he said turn right, she would turn left.”

“True, true,” Maybel agreed. “But I suspect that because he loves her, he will not allow her to remain in the storm even if she insists she will. He will bring her to shelter, never fear.”

And Maybel chuckled again.

“You are a most devious old woman,” Tom said admiringly. “And I never until now realized it.”

“I know my child,” Maybel told him.

They had reached the path that turned off up the hill to the border keep of Claven’s Carn. Rosamund brought their party to a halt as the man-at-arms they had sent ahead came riding down the hill.

“The laird and his wife bid you welcome,” he told them.

Rosamund turned to the captain of the men-at-arms. “All but two may go with my cousin, daughter, and the women,” she told him. “I will want torches to light the path for me, as I must go on as long as I can tonight.”

The captain shook his head. “Lady,” he told her, “we were hired to escort you home, and that we will do. But I will not expose my horses to certain death if you ride them through the night without proper shelter, food, and rest.”

“I will give you new horses,” Rosamund told him.

“You will kill my men,” he replied. “The answer is nay! Look about you! The hills are already shrouded in mist that will turn to fog before long. You will not be able to make enough headway to matter before you cannot even see the path before you with a light. Take shelter here.”

“I will not stop now,” Rosamund said. “Give me a torch, and I will travel on by myself.”

Tom thought his head was going to explode, but remembering what Maybel had advised, he said to the captain, “Let her have a damned torch!”

“My lord!” the man protested, but then he grew silent at Lord Cambridge’s look. “Yes, my lord,” he said, and then he handed Rosamund his own torch. “Lady,” he pleaded, “take shelter, I beg you.”

Ignoring him, Rosamund moved slowly forward, passing them and disappearing into the mist until only a pinpoint of light from her torch could be seen.

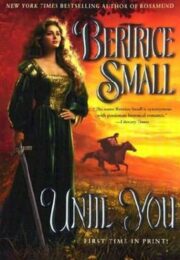

"Until You" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Until You". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Until You" друзьям в соцсетях.