Rosamund looked at him bleakly. “He does not know me,” she said again.

“Be patient,” Tom counseled her gently. He could almost feel the pain she was experiencing. “Be brave. You have always been.”

“I know,” Rosamund answered him, “but I love him, Tom. I have never before really loved anyone like this. I do not expect to love again, if ever, like this. If he does not remember me, remember us, what am I to do?”

“We will cross that water when we come to it, cousin,” he replied. “It is all we can do in this situation.”

She nodded slowly.

At first Rosamund was unable to go back to nursing the earl. But then Tom and Adam convinced her that if Patrick’s memory was to be jogged, she must be with him as much as she could. It was difficult, however, for he treated her like a complete stranger. He was polite, but distant.

“You had us all quite frightened,” she told him one afternoon in late April. “I wonder what made you finally open your eyes, my lord. We had almost given up hope.”

“I smelled white heather,” he told her.

And Rosamund remembered that she had bathed and washed her hair that day with her scented oils and soaps, which were all perfumed with white heather. “Did you?”

“You wear it,” he noted.

“Aye, I do,” she said. Remembering how he had always loved the scent, even bathing in it when they were in San Lorenzo.

“But that afternoon it was particularly strong,” he replied.

“I had just bathed,” she responded.

“My son tells me we are to marry,” he told her.

“We were,” she said.

“You do not wish to marry me now, madame?” His look was curious.

“How can I marry a man who does not remember who I am?” Rosamund asked him. “If your memory does not revive itself, my lord, there will be no marriage.”

“You do not wish to be a countess?” he asked.

Rosamund laughed almost bitterly. “I was not marrying you to become a countess, my lord. And before you ask it, I was not marrying you for wealth. I have wealth of my own. Nor were you wedding me for my wealth.”

“Then why were we marrying? I have a grown heir and two grandsons. I need no other bairns,” he said.

“You cannot have any more bairns, my lord. A fever burned your seed lifeless many years ago.” So there were other things he did not recall of his past. “We were wedding because we loved each other,” she told him.

“I had fallen in love at my age?” he laughed, but then he saw the stricken look upon her lovely face, and he said, “Forgive me, madame. It seems so odd to me that a man of my years should fall in love with so beautiful a young woman. And you returned my love?”

“I did. We spent last winter together, and you came back with me to Friarsgate in early summer. It was there we decided to wed. We would spend the spring and summer and early autumn there. In late autumn and winter we would live at Glenkirk,” she explained. “You believed that Adam had done so fine a job managing your lands in your absence that you might trust him completely now.”

“Though you say it is so, and I believe you, I can recall none of it,” he said to her.

“And you do not remember going to San Lorenzo last winter for the king?” she said.

“Nay, I do not,” he replied. “I would never have gone back to San Lorenzo. ’Twas there that my darling daughter, Janet, was taken from me. Nay. I would not go to San Lorenzo.”

“And yet you did because the king needed your help, and you are his loyal servant,” Rosamund said. “We spent a wonderful winter and early spring there. Our servants, Dermid and Annie, wed there with our blessing.”

“Dermid More is married?” He was genuinely surprised. Then he asked her, “What did Jamie Stewart want of me that he sent me back to San Lorenzo?”

“My king was harassing your king into joining what is called the Holy League,” Rosamund began. “Since the purpose of this alliance is against the French, your king would not join. He sent you to San Lorenzo in hopes you might weaken the alliance once you had spoken with the representatives of Venice and the Holy Roman Empire.”

“Did I succeed?” the earl asked.

“Nay. But while King James suspected you would not, he felt he had to try. We stopped in Paris on our way home to reassure King Louis of Scotland’s fidelity,” Rosamund finished. “You recall none of this?”

He shook his head. “Nothing, madame. I cannot believe I went back there.”

“You were reluctant,” she told him, “but we did go. And we were happy together in San Lorenzo.”

There was a long, awkward silence, and then he said, “I am sorry, madame, that my memory seems to have fled me.”

“What is the last thing you recall, my lord?” she questioned him.

Again he shook his head. “I was, I think, at Glenkirk,” he told her. Then he asked, “What year is this, madame?”

“It is April in the year of our Lord, fifteen hundred and thirteen, my lord,” Rosamund told him. “And we are in Edinburgh.”

He looked genuinely surprised. “Fifteen hundred and thirteen,” he repeated. “I thought it was the year fifteen hundred and eleven, madame. I seem to have lost two years of my life. But I believe I remember most of the rest of it.”

“I am glad for that, my lord,” Rosamund said softly. She blinked back the tears she felt pricking at her eyelids. Weeping would change nothing.

“When,” he asked her, “do you think I shall be well enough to return to Glenkirk?”

“I believe we must ask Master Achmet,” Rosamund responded.

“I do not like these dark-skinned Moors,” he noted. “A dark-skinned slave betrayed my daughter.”

“He is highly thought of by the king,” Rosamund answered him. “The king sent him to you when you fell ill, my lord. His care of you and advice have been excellent.” She arose from her seat by his bedside. “I think, my lord, you had best take your rest now. I shall leave you.”

“I am being treated like an old man,” he grumbled. “I think you are well rid of me, madame. When shall I be able to leave this bed of mine?”

“We shall ask Master Achmet that, too, when he comes today,” Rosamund repeated as she slipped from the room. Outside in the hallway, she sighed. His memory of the last two years was not returning, and her hopes for their reunion were slowly fading. She felt hollow and more alone than she had ever felt in her entire life. And the casual words he had spoken, saying she was well rid of him, had been like a blow to her heart.

Philippa Meredith turned nine years old on the twenty-ninth of April. The Earl of Glenkirk was allowed into the hall for her birthday dinner. He had been walking about his bedchamber for several days now, and his physical strength seemed to be returning. The little girl was shy of the earl now, for he considered her a stranger. It was difficult for her to understand, but her manners were impeccable. In the stress of the situation everyone forgot Rosamund’s twenty-fourth birthday on the thirtieth of the month.

Plans were now being made for the Leslies to return to Glenkirk, and for Rosamund and her family to go home to Friarsgate. Lord Cambridge escorted his cousin to see the queen. Margaret Tudor had been advised of the state of affairs. She held out her two hands to Rosamund as her old friend entered her privy chamber. There was nothing even she could say, she knew, that could help the situation. The two women embraced.

“I pray you never know such sorrow and pain as I do now,” Rosamund told her.

“He remembers not at all?” the queen said.

“Almost everything up until two years ago. Master Achmet says it may all come back eventually. It is the best I can hope for, Meg.” They were alone.

“I will pray for it, and for you, dear Rosamund,” the queen said.

Prince James was brought and displayed for the lady of Friarsgate. He was a healthy- and ruddy-looking little boy, but Rosamund saw little of the Tudors in him. Finally, her visit at an end, Rosamund took her leave of the queen.

“There will be war soon,” Meg said. “Keep safe, dear Rosamund.”

“Do you really think so?” Rosamund replied.

The queen nodded. “My brother will not listen to reason. He is as ever stubborn. He is forcing Scotland to the wall over this damned Holy League.” She sighed. “You should be safe, but keep watch.” She pulled a ring from her finger. “If Scots invade your lands, show them this ring and say the Queen of Scotland gave it to you and says you are to be free of harassment.”

Rosamund felt tears fill her eyes. “Thank you, your highness,” she said, addressing Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scotland, formally. Damn! She cried so easily these days. The two women embraced a final time, and then Rosamund backed from the queen’s privy chamber and departed the royal residence.

Chapter 13

Rosamund returned to her cousin’s house. It was the second day of May, and preparations were now well under way for their departure on the morrow. Both parties would be leaving in the morning. The Leslies would be going northeast to Glenkirk. The Boltons would travel southwest to Friarsgate. Adam knew how devastated Rosamund was and how she strove to hide it from them all, especially her little daughter. He sat together with her in the hall after everyone else had gone to bed.

“If he remembers, I will send to you,” Adam promised her.

“My instincts tell me he will not remember,” Rosamund replied. “When your father and I met it was as if lightning had struck us. From that first moment our gazes joined, we knew that whatever had been between us in another time and place must once again be between us. But we also had a knowing, a foreboding if you will, that we would not be allowed to remain together in this life. As our love for each other grew even greater, however, we pushed that shared premonition into the back of our minds. We pretended that it was simply we did not know how to do our duty to both Glenkirk and Friarsgate if we wed. And then we resolved this difficulty, which allowed us to plan our marriage. But fate will not be denied, Adam Leslie. Patrick and I were not meant to be forever more. And fate has once again taken a hand in the matter.” She sighed. “Your father will live out the rest of his life without ever remembering those glorious months we had together or how passionately we loved each other. I, on the other hand, will never forget. That is my punishment for attempting to defy fate,” Rosamund concluded sorrowfully.

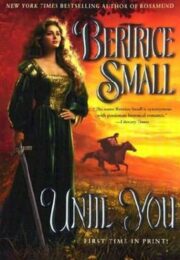

"Until You" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Until You". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Until You" друзьям в соцсетях.