Her father seemed as unaware of Sheridan's efforts as he was of her failures and her grief. Then one fateful day, she burned both her arm and the eggs she'd cooked for him. Trying not to cry from the pain in her arm or the pain in her heart, she had lugged the wash down to the stream along with what was left of the lye soap. As she knelt on the bank and gingerly lowered her father's flannel shirt into the water, scenes from the happy past at this same spot came back to haunt her. She remembered the way her mama used to hum as she did the wash here while Sheridan supervised little Jamie's bath. She remembered the way Jamie used to sit in the water, gurgling happily, his chubby hands smacking the water in playful glee. Mama had loved to sing; she'd taught Sheridan songs from England and sung them with her while they worked. Sometimes she would stop singing and simply listen to Sheridan, her head tipped to the side, a strange, proud smile on her face. Often she would wrap Sheridan in a tight hug and say something wonderful, like, "Your voice is very sweet and very special-just like you are."

Memories of those idyllic days made Sheridan's eyes ache as she knelt at the stream. The words of her mama's favorite song whispered in her mind, along with the memory of her mama smiling, first at Jamie as he giggled and splashed, and then at Sheridan, who was usually getting soaked too. "Sing something for us," she would say. "Sing for us, angel…"

Sheridan tried to obey the remembered request, but her voice broke and her eyes flooded with tears. With the heels of her hands, she rubbed the tears away only to discover that her father's shirt was now floating downstream, already out of her reach, and then Sheridan lost the battle to be brave and grown-up. Drawing her knees against her chest, she buried her face in her mama's apron and sobbed with grief and terror. Surrounded by summer wildflowers and the scent of fresh grass, she rocked back and forth, crying until her throat ached and her words were only a croaking whispered chant. "Mama," she wept, "I miss you, I miss you, I miss you. I miss Jamie. Please come back to Papa and me. Please come back, please come back. Oh, please. I can't do it alone, Mama. I can't do it. I can't, I can't-"

Her litany of grief was suddenly interrupted by her father's voice-not the dull, lifeless, terrifyingly unfamiliar voice he'd had for months, but his old voice-hoarse now with concern and love. Crouching beside her, he'd pulled her into his arms. "I can't do it alone either," he'd said, cradling her tightly against him. "But I'll wager we can do it together, sweeting."

Later, after he'd mopped her tears, he'd said, "How would you like to leave here and go travelling, just you and me? We'll make every day an adventure. I used to have great adventures. That's how I met your mama-I was having an adventure in England, in Sherwyn's Glen. Someday, we'll go back to Sherwyn's Glen, you and me. Only not the way your mama and I left. This time, we'll go back in grand style."

Before Sheridan's mama died, she'd talked nostalgically about the picturesque village in England where she'd been born, about its beautiful countryside, its treelined lanes, and the dances she'd attended at the assembly rooms there. She'd even named Sheridan after a particular kind of rose that bloomed at the parsonage, a special species of red rose that she said bloomed in gay profusion along the white fence surrounding the parsonage.

Sheridan's father's preoccupation with returning to Sherwyn's Glen seemed to start after her mother's death. What puzzled Sheridan for a long while, however, was exactly why her papa wanted to go back there so badly, particularly when the most important man in the village seemed to be an evil, proud, monster of a man named Squire Faraday who lorded it over everyone and who would not make a good neighbor at all when her papa built his mansion right next to his home, which was his intention.

She knew her papa had first met Squire Faraday when he delivered a very valuable horse from Ireland that the squire had purchased for his daughter, and she knew that since her father had no close family alive in Ireland, he'd decided to stay on and work for the squire as a groom and horse trainer. But not until she was eleven years old did she discover that the wicked, coldhearted, hateful, arrogant Squire Faraday was actually her mama's own father!

She'd always wondered why her father had taken her mother away from her beloved village and then spirited her off to America, along with her mother's elder sister, who then settled in Richmond and refused to budge another inch. It had always seemed a little strange that the only thing they took with them, besides the clothing on their persons and a small sum of money, was a horse called Finish Line-a horse that her mama had loved enough to bring along and pay his passage, and yet one she had sold soon after they arrived in America.

The few times her parents had spoken of their departure from England, it had always seemed hasty somehow, and vaguely unhappy too, but she couldn't imagine why that would have been so. Unfortunately, her father was adamantly unwilling to satisfy her curiosity on that score, which left her with no choice except to rein in her curiosity and wait until they built their mansion in Sherwyn's Glen so that she could find out for herself. She planned to accomplish her goal by asking all sorts of carefully veiled questions once she got there. As far as she could tell, her father intended to accomplish his goal by gambling at cards and dice, with whatever money they could actually spare and as often as he found a good game of either underway. The fact that he simply wasn't lucky at cards and dice was apparent to both of them, but he believed all that would change someday. "All I need, darlin'," he would say with a grin, "is just one nice, long lucky streak at the right table. I've had a few of those in my time, and my time is comin' again. I can feel it."

Since he never lied to her, Sherry believed it too. And so they travelled together, talking to each other about subjects as mundane as the habits of ants and as grand as the creation of the universe. To some people, their vagabond lifestyle must have seemed strange. It had seemed that way at first to Sherry too, strange and frightening, but she soon came to love it. Before they'd left the farm, she'd truly thought the whole wide world looked exactly like their own little patch of meadow and that hardly anyone existed beyond its boundaries. Now there were new sights to see around every bend in the road and the happy expectation of meeting interesting people along their route who were heading in the same direction-travellers who were bound for, or en route from, places as distant and exotic as Mississippi, or Ohio, or even Mexico!

From them, she heard wondrous stories of far-off places, amazing customs, and strange ways of life. And because she treated everyone as her papa did-with friendliness, courtesy, and interest-many of them chose to match their pace to the Bromleighs' wagon for days at a time or even weeks. Along the way, Sheridan learned even more: Ezekiel and Mary, a Negro couple with skin like smooth shiny coal, springy black hair, and hesitant smiles told her about a place called Africa, where their names had been different. They taught her a strange, rhythmic chant that wasn't quite a song, yet it made her spirits heighten and quicken.

A year after Mary and Ezekiel went their own way, a white-haired Indian with skin as weathered and wrinkled as dried leather appeared around a bend in the road one gray winter day, mounted upon a beautiful spotted horse that was as young and energetic as his rider was old and weary. After considerable encouragement from Sheridan's father, he tied his horse to the back of the wagon, climbed aboard, and, in answer to Sheridan's inquiry, he said his name was Dog Lies Sleeping. That night, seated at their campfire, he responded to Sheridan's question about Indian songs by giving a strange demonstration of one, a demonstration that seemed to consist of guttural sounds accompanied by the beating of his palms on his knees. It sounded so odd and unmelodic that Sheridan had to bite back a smile for fear of hurting his feelings, and even then he seemed to sense her bewildered amusement. He broke off abruptly and narrowed his eyes. "Now," he said, in his abrupt, commanding voice, "you make song."

By then, Sheridan was as used to sitting around campfires and singing with strangers as she was speaking to them, and so she sang-an Irish song that her papa had taught her about a young man who lost his love. When she got to the part about the young man weeping in his heart for his beautiful lassie, Dog Lies Sleeping made a strangled noise in his throat that sounded like a snort and a laugh. A swift glance across the fire at his appalled expression proved her guess was correct, and this time it was Sheridan who broke off in mid-note.

"Weeping," the Indian informed her, in a lofty, superior tone while pointing his finger at her, "is for women."

"Oh," she said, chagrined. "I-I guess Irish men are, well, different because the song says they cry, and Papa taught it to me, and he's Irish." She looked for confirmation to her father and said hesitantly, "Men from the old country do cry, don't they, Papa?"

He shot her a laughing look as he dumped the dregs of his coffee onto the fire and said, "Well, now, darlin', what if I say they do, and Mr. Dog Lies Sleeping leaves us thinkin' for all time that Ireland's a sad place filled with sorry lads all weepin' their hearts out and wearin' them on their sleeves? That wouldn't be a good thing, would it? And yet, if I say they don't cry, then you might end up thinkin' the song and I lied, and that wouldn't be good, either." With a conspiratorial wink, he finished, "What if I say you misremembered the song, and it's really the Italians who cry?"

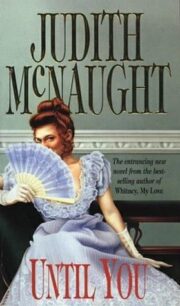

"Until You" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Until You". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Until You" друзьям в соцсетях.