‘Pyotr, come on, he’s waiting for us.’

‘Who?’ He trotted alongside her, pulling on his varezhki, woollen mittens, his boots crunching through the snow.

‘Rafik.’

‘Zenia, wait a minute.’ Pyotr was baffled. ‘What does he want with me?’

‘Hurry up.’

‘I am hurrying.’

‘Your father is coming home.’

Pyotr sobbed, a strange animal sound he’d never heard before. Around him Tivil looked the same, the roofs edged with blue icicles, the woodpiles stacked high, the picket fences hibernating under their coating of snow. Still the same dull old village, but suddenly it had changed. Now everything shone bright and dazzling to welcome Papa home.

His excitement had cooled. The wind and the snow and the sound of ice cracking on the river had stolen its heat. They’d been waiting on the road into the village for so long now, but nobody had come and he’d started to believe they were wrong. Though Rafik had given him a smile of welcome when he’d first arrived, now the gypsies paid him little heed. They talked in intense low voices in a tight huddle, excluding him.

‘When’s Papa coming?’ he asked again.

‘Soon.’

Soon had come and gone.

But now Rafik said urgently, ‘A horse is coming.’

Pyotr was the first to hear the whinny of the horse. He straightened up and stared out past Zenia, wrapped in her thick coat and headscarf, into the shifting banks of fog where the road should be. It was like floating into another world, unfamiliar and unpredictable.

‘Pyotr.’

The word drifted, swirling and swaying towards him through the air.

‘Papa!’ Pyotr yelled, ‘Papa!’

Out of the wall of white loomed a tall figure in a filthy coat. At his side hobbled a small grey horse.

‘Papa,’ Pyotr tried to shout again, but this time the word choked in his throat.

He flew into the outstretched arms, burrowed his face into the icy jacket and listened to his father’s heart. It was real. Beating fast. The cloth of the jacket smelled strange and the beard on his face felt prickly, but it was his Papa. The big strong familiar hands gripped him hard, held him so close Pyotr couldn’t speak.

‘What’s going on here?’ his father demanded over his head.

‘We’ve been expecting you,’ the gypsy responded.

Mikhail gently disentangled himself from his son and held out a hand to Rafik. The gypsy grasped it with a fervour that took Pyotr by surprise.

‘Thank you, Mikhail,’ Rafik murmured. Not even the chill moan of the wind could conceal the joy in his voice.

Then for the first time Pyotr noticed the person behind his father.

‘Sofia!’ he gasped.

‘Hello, Pyotr.’ She smiled at him. Her face was painfully thin. ‘You look well,’ she said.

In her voice he could hear no trace of anger at what he’d done, just a warmth that defied the cold around them.

‘Did you miss us?’ she asked.

‘I missed your jokes.’

She laughed. His father ruffled his hair under the fur hat, but his look was serious. ‘Pyotr, we’ve brought Sofia’s friend back with us.’

He gestured at a dark shape lying on the horse. It was strapped on the animal’s back, skin as grey as the horse’s coat, but the figure moved and struggled to sit up. At once Pyotr saw it was a young woman.

‘We have to get her out of the cold,’ Papa said quickly.

Sofia moved close to the horse’s side. ‘Hold on, Anna, just a few minutes more. We’re here now, here in Tivil, and soon you’ll be…’

The young woman’s eyes were glazed and Pyotr wasn’t sure she was even hearing Sofia’s words. She attempted to nod but failed, and slumped forward once more on the horse’s neck. Sofia draped an arm round her thin shoulders.

‘Quickly, bistro.’

Rafik and Zenia led the way, heads ducked against the swirling snowflakes that stung their eyes. Pyotr and Mikhail started to follow as fast as they could, with Mikhail leading the little grey mare. Sofia walked at its side, holding the sick young woman on its back. Pyotr could hear his father’s laboured breathing, so he seized the reins from his hand and tucked himself under Papa’s arm, bearing some of his weight. The horse dragged at every forward pace and Pyotr was suddenly frightened for it. Please, don’t let it collapse right here in the snow.

The sky was darkening. Pyotr could sense the village huddle deep in its valley, shutting out the world beyond. Something stirred inside him, something strong and possessive, and he tightened his grip on his father. The snow underfoot was loose and slippery but, instead of stopping at his own house, the little procession continued right past it.

‘Where are we going, Papa?’

His father didn’t speak, not until they stood outside the izba that belonged to the Chairman. It hunched under its coat of snow, shutters closed and smoke billowing from its chimney.

‘Aleksei Fomenko!’ Mikhail bellowed against the wind. He didn’t bother knocking on the black door. ‘Aleksei Fomenko! Get out here!’

The door slammed open and the tall figure of the Chairman strode out into the snow, dressed in no more than his shirtsleeves, the wolfhound a shadow behind him.

‘Comrade Pashin, so you’ve decided to return. I didn’t expect to see…’

His eyes skimmed over Mikhail and Pyotr, past the gypsies, and came to an abrupt halt on Sofia. His jaw seemed to jerk as if he’d been hit. Then his gaze shifted to the wretched horse. No one spoke. Fomenko was the first to move. He ran over to the horse and, working fast but with great care, he untied the straps.

‘Anna?’ he whispered.

She raised her head. For a moment her eyes were blank and glazed, but snowflakes settled on her lashes, forcing her to blink.

‘Anna,’ he said again.

Gradually life trickled back into her eyes. She pushed herself to sit up and stared at the man by her side, as though uncertain whether her mind was confusing her.

‘Vasily, are you real? Or another ghost of the storm?’

He took her mittened hand in his and pressed it to his cold cheek. ‘I’m real enough, as real as the sleigh I built for you and as real as the songs you sang for me. I still hear them when the wind blows through the valley.’

‘Vasily,’ she sobbed.

She struggled to climb off the horse but Fomenko lifted her from the saddle as gently as if he were handling a kitten, cradling her in his arms away from the driving snow. Her head lay on his chest and he kissed her dull, lifeless hair. He turned to face Sofia and Mikhail.

‘I’ll care for her,’ he said. ‘I’ll buy the best medicines and make her well again.’

‘Why?’ Sofia asked. ‘Why now and not before?’

Fomenko looked down at the pale woman in his arms and his whole face softened. He spoke so quietly that the wind almost snatched his words away.

‘Because she’s here.’

Pyotr saw that Sofia’s cheeks were wet. He didn’t know if it was snow or tears.

Fomenko turned away from the watching group. At a steady pace so as not to jar her fragile bones, the dog walking ahead of him over the snow, he carried Anna into his house in Tivil.

The air was warm. That was the first thing Anna absorbed. Her bones had lost the agonising ache that had pulled at them for so long and seemed to be melting from inside, they felt so soft and heavy. She opened her eyes.

She’d forgotten what it was like to feel like this, so comfortable, so cosseted, a downy pillow under her head, a clean-smelling sheet pulled up to her neck. No brittle ice like jagged glass in her lungs. She tried breathing, a swift swallow of the warm air.

Bearable.

Her gaze explored the room, sliding with slow consideration over the curtains, the chair, the carpet, the shirts hanging on hooks, all full of colour. Colour. She hadn’t realised how much she’d missed it. In the camp everything had been grey. A small sigh of pleasure escaped her, a faint sound, but it was enough. Instantly a whining started up outside the bedroom door and brought her back to reality.

Whose house was she in? Mikhail’s? Or… No. She shook her head. No, it wasn’t Mikhail’s. Only dimly did she recall being carried in a pair of strong arms, but she knew exactly whose bed she was lying in and whose dog was whining at the door.

The latch lifted quietly. Anna’s heart stopped as her eyes sought out the figure standing in the shadows. He was tall, holding himself stiffly, and in a flash of anxiety she wondered whether the stiffness was in his mind or his body. His shirt fitted close across his wide chest, and his hair was cropped hard to his head.

Vasily. It was Vasily, with the Dyuzheyev forehead, the long aristocratic nose – and the eyes, she remembered those grey swirling eyes. But the once generous mouth was now held tight in a firm line. At his heel stood a large rough-coated wolfhound; Anna recalled Sofia telling her its name.

‘Hope,’ she breathed. It was easier than saying Vasily.

The dog loped towards her, its claws clipping the wooden floor, and nuzzled her hand. The simple display of affection seemed to persuade Vasily at last to walk into the room, but there was something deliberately formal in his step and he came no nearer than the end of the bed.

He spoke first. ‘How are you feeling?’

His voice was controlled, and deeper than it used to be, but she could still hear the young Vasily in it. A shiver of pleasure shot through her.

‘I’m fine.’

‘Are you cold? Do you need another quilt?’

‘No. I’m warm, thank you.’

Another awkward silence.

‘Are you hungry?’

She smiled. ‘Ravenous.’

He nodded and, though he didn’t move away, his eyes did. They looked at the dog’s shaggy head now resting on the quilt, at the round wooden knobs at each corner of the bed, at the white-painted wall, at the window and a gust of snowflakes sweeping across the yard outside. Anywhere but at her.

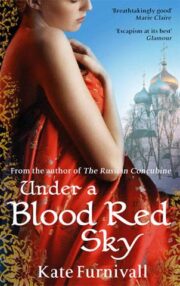

"Under a Blood Red Sky" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky" друзьям в соцсетях.