"You, on the other hand," Paul said. "I think you're destined for a career in the social services. You're a natural-born do-gooder."

"Yeah," I said, as I stopped beside my locker. "Maybe I'll follow in Father D's footsteps, and become a nun."

"Now that," Paul said, leaning against the locker next to mine, "would just be a waste. I was thinking more along the lines of a social worker. Or a therapist. You're very good, you know, at taking on other people's problems."

Wasn't that the truth? It was the reason I was so bleary-eyed and tired today. Because after I'd left Jesse the night before, I'd driven home and gone up to bed . . . only not to sleep. Instead, I'd lain awake, blinking at the ceiling and mulling over what Jesse had told me. Not about Paul, but about what Paul had made me read aloud earlier that day: The shifter's abilities didn't merely include communication with the dead and teleportation between their world and our own, but the ability to travel at will throughout the fourth dimension as well.

The fourth dimension. Time.

The very word caused the hairs on my arms to stand up, even though it was another typically beautiful autumn day in Carmel and not cold at all. Could it really be true? Was such a thing even possible? Could mediators - or shifters, as Paul and his grandfather insisted on calling us - travel through time as well as between the realms of the living and the dead?

And if - a big if - it were true, what on earth did it mean?

More important, why had Paul been so intent on making sure I knew about it?

"You look strung out," Paul observed as I stowed my books away and reached for the paper bag containing the lunch my stepfather had made me: tandoori chicken salad. "What's the matter? Trouble sleeping?"

"You should know," I said, glaring at him.

"What'd I do?" he asked, sounding genuinely surprised.

I don't know if it was my exhaustion, or the fact that that the career aptitude test had got me thinking about my future . . . my future and Jesse's. Suddenly, I was just very tired of Paul and his games. And I decided to call him on the latest one.

"The fourth dimension," I reminded him. "Time travel?"

He just grinned, however. "Oh, good, you figured it out. Took you long enough."

"You really think shifters are capable of time travel?" I asked.

"I don't think so," Paul said. "I know so."

Again, I felt a chill when I shouldn't have. We were standing in the shade of the breezeway, it was true, but just a few feet away in the Mission courtyard, the sun was blazing down. Hummingbirds flitted from hibiscus blossom to hibiscus blossom. Tourists snapped away with their digital cameras.

So what was up with the goose bumps?

"Why?" I demanded, my throat suddenly dry. "Because you've done it?"

"Not yet," he said, casually. "But I will. Soon."

"Yeah," I said, fear making me sarcastic. "Well, maybe you could travel back to the night you stole Mrs. Gutierrez's money and not do it this time."

"God, would you let it go already?" He shook his head. "It was two thousand lousy bucks. You act like it was two million."

"Hey, Paul." Kelly Prescott broke away from her clique - the Dolce and Gabbana Nazis as CeeCee had taken to calling them - and sauntered over, fluttering her heavily mascaraed eyelashes. "You coming to lunch?"

"In a minute," Paul said to her . . . not very nicely, considering she was his date for next weekend's dance. Kelly, though stung, nevertheless pulled herself together enough to send me a withering glance before heading for the yard where we dined daily, al fresco.

"So I don't get it." I stared at him. "What if we can travel through time? Big deal. It's not like we can change anything once we get there."

"Why?" Paul's blue eyes were curious. "Because Doc from Back to the Future said so?"

"Because you can't . . . you can't mess up the natural order of things," I said.

"Why not? Isn't that what you do every day when you mediate? Aren't you interfering with the natural order of things by sending spirits off to their just reward?"

"That's different," I said.

"How so?"

"Because those people are already dead! They can't do anything that might change the course of history."

"Like Mrs. Gutierrez and her two thousand dollars?" Paul's glance was shrewd. "You think if you'd given it to her son, it wouldn't have changed the course of history? Even in some small way?"

"But that's different than entering another dimension to change something that already happened. That's just . . . wrong"

"Is it, Suze?" A corner of Paul's mouth lifted. "I don't think so. And you know what? I think this time, your boy Jesse is going to agree. With me."

And suddenly, it seemed to get even colder than ever under that breezeway.

Chapter six

Please be home, please be home, please be home, I prayed as I waited for someone to answer the doorbell. Please please please please . . .

I don't know if someone heard my prayer, or if it was just that invalid archeologists don't get out that much. In any case, Dr. Slaski's attendant answered the front door, recognition dawning when he saw that it was me who'd been ringing the bell with so much urgency.

"Oh hi, Susan," he said, getting the name wrong, but the face that went with it right. Sort of. "You looking for Paul? Because far as I know, he's still in school - "

"I know he's still at school," I said, stepping hurriedly inside the Slaters' foyer, before the attendant could close the door. "I'm not here to see him. I stopped by to see his grandfather, if that's all right."

"His grandfather?" The attendant looked surprised. And why shouldn't he? For all he knew, his patient hadn't had a lucid conversation with anyone in years.

Except that he had. And it had only been a few months ago. With me.

"You know, Susan, Paul's grandpa isn't . . . He's not real well," the assistant said slowly. "We don't like to talk about it in front of him, but his last round of tests . . . Well, they didn't look so good. In fact, the doctors aren't giving him all that much longer to live . . ."

"I just need to ask him a question," I said. "Just one little question. It'll only take a second."

"But . . ." The attendant, a young guy who, judging from his sun-bleached dreads, probably used whatever spare time he got to hit the waves, scratched his chin. "I mean, he can't . . . he doesn't really talk all that much anymore. The Alzheimer's, you know . . ."

"Can I just try?" I asked, not caring that I sounded like a whacko. I was that desperate. Desperate for answers that I knew only one person on earth could give me. And that person was just right upstairs. "Please? I mean, it couldn't hurt, could it?"

"No," the attendant said slowly. "No, I guess it couldn't hurt."

"Great," I said, slipping past him and starting up the stairs two at a time. "I'll just be a couple of minutes. You won't mind leaving us alone, will you? I'll call you if he looks like he might need you."

The attendant, closing the front door in a distracted sort of way, went, "Okay. I guess. But . . . shouldn't you be in school?"

"It's lunchtime," I informed him cheerfully, as I made my way up the stairs and then down the hall toward Dr. Slaski's room.

I wasn't lying, either. It was lunchtime. The fact that we weren't technically supposed to leave school grounds at lunch? Well, I didn't feel that was important to mention. I was less worried about facing the wrath of Sister Ernestine when she found out I was skipping school than I was about explaining to my stepbrother Brad why I'd so desperately needed the keys to the Land Rover. Just because Brad had happened to get his driver's license about five seconds before I'd gotten mine (well, okay, a few weeks before I'd gotten mine, actually), he seems to feel that the ancient Land Rover, which is supposed to be the "kids' car," belongs solely to him, and that only he's allowed to ferry the two of us, plus his little brother, David, to and from school every day.

I'd had to resort to using the words "feminine hygiene products" and "glove compartment" just to get him to surrender the keys. I had no idea what he was going to do when I didn't return before the end of lunch and he discovered the car was gone. Narc on me, doubtlessly. It seemed to be his one joy in life.

Sadly, I never seem able to return the favor, thanks to Brad generally having some kind of goods on me.

In any case, I wasn't going to squander what precious little time I had wondering what Brad was going to say about my taking the car. Instead, I hurried into Paul's grandfather's bedroom.

As usual, the Game Show Network was on. The attendant had parked Dr. Slaski's wheelchair in front of the plasma screen television. Dr. Slaski himself, however, appeared to be paying no attention whatsoever to Bob Barker. Instead, he was staring fixedly at a spot in the center of the highly polished tile floor.

I wasn't fooled by this, however.

"Dr. Slaski?" I picked up the remote and turned the TV volume down, then hurried to the doctor's side. "Dr. Slaski, it's me, Suze. Paul's friend, Suze? I need to talk to you for a minute."

Paul's grandfather didn't respond. Unless you call drooling a response.

"Dr. Slaski," I said, pulling up a chair so that I could sit closer to his ear. I didn't want the attendant to overhear our discussion, so I was trying to keep my voice low. "Dr. Slaski, your nurse isn't here and neither is Paul. It's just the two of us. I need to talk to you about something Paul's been telling me. About, er, mediators. It's important."

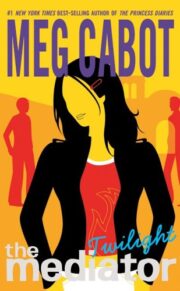

"Twilight" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Twilight". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Twilight" друзьям в соцсетях.