“I miss him too, you know,” she said, tracing a pattern on the table with a nail coated in chipped navy varnish.

“I know. I—”

“Don’t you dare say you’re sorry, Ty. Don’t you dare.”

“I wasn’t going to.” How could sorry even start to cover the span of my guilt?

She gave me a sidelong look and a smile. “Of course you weren’t.”

I said what I should have said straightaway. “I was going to say that I’m here if you need me.”

Penny nodded, as if she was trying to shake off the tears I could see were falling. “I need you, Ty.”

I closed my eyes and dipped my forehead to rest on hers. I wanted to tell her that this was a bad idea. That I wasn’t the person she thought she needed. Only I couldn’t do that to her. Or to me. I’d already lost one best mate. I couldn’t lose the other.

That was two weeks after Chris died — eight more to live through until the inquest. Eight more weeks in which I hid the truth from Penny. I don’t know what I thought would happen after that — I’m not sure I was thinking at all — but when the time came to go to the magistrates’ court, I told Penny one last lie about having a doctor’s appointment and went with my parents to face whatever judgement was cast.

The purpose of the inquest was to go over the witness statements and confirm the circumstances that led to Chris’s death by questioning the witnesses — me and the woman driving the car — on points that had not yet been cleared up. Every word I heard myself say seemed to hammer home my guilt, discussing the fight in details that were only too easy to recall because I relived them every waking second. And I hoped for something to change, that I would finally be exposed for what I was, finally made accountable.

The verdict was death by misadventure.

Death by misadventure. That’s a phrase that plays in my head sometimes, the way a fragment of a tune, or a poem might, cropping up to remind me that nothing multiplies guilt like the implication of innocence. As if I’ve ever been close to forgetting.

As I walked out with my parents I saw Chris’s dad waiting by the doors as his wife came out of the toilets, her face blotched red from tears I’d caused. I wanted to tell her that I was so sorry — not just for what I’d done, but that I wasn’t about to be punished for it — but she beat me to it.

“You killed him!” A sentence that started in a hiss and ended in a shriek. Out of the corner of my eye I saw a few people turn towards us. “My son is dead because of you…”

“I—” But she was sobbing into her hands and I could see her tears spilling out through her fingers as Chris’s dad put his arm around her and pulled her into him. I expected him to be angry too — Mr Lam’s temper was legendary — but when he looked at me, his eyes weren’t blazing with fury, they were dull, deadened with loss.

“Go away, Ty,” he said, pulling his wife close as I felt my mum’s hand on my arm. “You’ve done enough damage.”

The next day was worse.

When I got to school, I saw one of the lads I sat with in ICT was waiting by the front doors. As I reached them he handed me a rolled-up newspaper.

“I thought you should know,” he said as he went inside.

I unrolled the paper to face a photo of Chris on the front page.

There had been a reporter from the local paper at the inquest, one who had given Chris’s parents a sympathetic ear. Chris was the fourth “youth” to die on the region’s roads in as many months and the paper was at the heart of a campaign to impose lower speed limits in residential areas. That morning the paper had been delivered to every house within a ten-mile radius of our school.

My hands started to tremble as I read the article, littered with quotes from my friend’s grieving parents. It told how their son had been fighting by the side of the road with a friend, “a typical bit of teenage rough and tumble”, which had turned to tragedy when Chris fell into the path of a car. It led on to say that though the driver hadn’t been speeding, the way Chris had fallen… I couldn’t see the words, I was shaking so much.

I was scared of going inside. No one in the school needed to see my name in print to know who Chris had been with. My hand looked strange on the door as I summoned up the courage to push it open. The world felt tilted, unreal, as I walked down the corridor. I could feel people looking at me, but I didn’t dare meet their gaze.

Penny was waiting by my locker, her friends clustered nearby, kept away by the forcefield of fury that surrounded her. As soon as I was within striking distance she lashed out, the slap stinging my skin. I saw her pull back for another, but she hesitated, fingers curling like a dying flower until her fist fell limply against my chest, fresh tears falling from closed eyes.

I tried to hold her, but she pushed me away.

It’s not like she’ll come running to you…

“Penny, I—”

“Don’t you dare say you’re sorry, Ty.”

I didn’t know what else to say.

“It says you were fighting. What were you fighting about? What could be so important that you’d push him in front of a moving car?”

“I didn’t” — I closed my eyes, saw my hand letting go of his jacket, his foot on the kerb — “push him.” It was barely a whisper.

“What were you fighting about?”

But I shook my head. I would have confessed to pushing him rather than tell Penny that the boy she loved, the one she mourned so keenly, had slept with someone else.

“Tell me!”

“It’s not important.”

“How can you say that?” Penny screamed in my face, battering my chest with her fists. I tried to put my arms around her, but she fought me away and ran off down the corridor. I made to go after her, but there was a hand on my arm, a warning, “Leave her, mate.”

I didn’t want to hear it and I spun round in anger, my fist bunched and flying, remembering how it felt to fight. Wanting something to take me away from what was happening…

I punched Rav so hard that I broke his jaw. And my hand.

HANNAH

“What happened after that?” I ask.

“I was suspended. My parents decided I needed a fresh start and whisked me away to Australia for the summer whilst they sorted out the house.” He’s staring across the room and his face is gentle, like he’s thinking about how grateful he is that they’d do that.

But that wasn’t what I’d meant. “I meant with Penny.”

Aaron shakes his head, once to each side and the look of loss on his face slays me. “That was it: friendship over. She never spoke to me again and I made it easy for her. I faded out of my own life and when we decided to move I shut down my Facebook account, changed my email address and got a new phone.”

I could never have done that, shut off my whole life in one go. “So you never told her why you and Chris were fighting?”

“I’ve only ever told one person the truth about that.” Aaron looks at me and takes a sip of Diet Coke.

“Not even…” I don’t say Neville’s name, but I see Aaron close his eyes, a gentle “No” formed on his lips.

I find myself staring at his mouth long after his lips have stopped moving.

AARON

Neville might have left, but Hannah’s still here, in spite of all I’ve done to push her away. Now, when I look at her, I finally see someone I trust. Someone I love.

HANNAH

Our faces are close enough that all I can see are his eyes and I see something there. Something promising.

Slowly, I tilt my mouth to his until our lips touch, until there’s only a kiss between us.

AARON

I lift my hand up to rest on her hair…

There’s a cough in the doorway and we pull apart, guilty.

“Aaron?” Hannah’s mum says. “It’s your parents on the phone.”

THURSDAY 15TH APRIL

EASTER HOLIDAYS

AARON

My parents are — understandably — pretty upset. Mum in particular. Yesterday she blamed herself for putting me in a vulnerable position. Of course I was going to get attached to Neville, she should have seen it coming, how could she have been so stupid? It took me a long time to explain to her that what she’d done had made all the difference. Without Cedarfields, without Neville, I’d never have made it this far. The reason I was so upset about losing him was because he’d been there when I needed him most. I’m not sure she understood, but it was late and we were all tired.

Tonight is a different matter. Tonight she’s mad with me.

“I don’t know what to do with you.” I stay quiet. “This time last year I didn’t have any grey hairs. That’s impressive for a woman my age, but now…” She leans forward and runs a finger along her scalp, joining up single grey hairs like an astronomer grouping constellations. “Look. I’m nearly as grey as your gran.”

Dad and I raise our eyebrows at each other.

“Don’t think I didn’t see that,” Mum says, sitting up again. “Aaron, you have got to stop doing this to us. I’m serious.”

“Doing what?” But I know.

“Scaring us.” Her eyes sparkle with unshed tears. “You don’t know what it’s like, being a parent…”

I think about that night in the car with Robert.

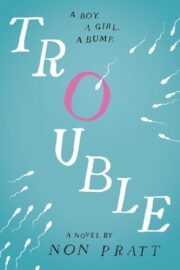

"Trouble" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Trouble". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Trouble" друзьям в соцсетях.