Into the road.

There’s a thousand little things that go into making one big thing happen. Wet tarmac, a car going a little too fast to catch the green light ahead, a boy who fell backwards when he should have fallen forwards, a boy who shouldn’t have let go of his friend’s sleeve when he did.

When you see something truly awful happen, you don’t process it at all — it’s only afterwards that details come to you. The only thing that registered with me was the noise: a sickening crack and thunk, both sharp and blunt, the sound of a body hitting a bonnet and breaking. It’s the noise I hear in my worst nightmares.

Chris was twisted all wrong on the ground and there was something darker than the rain pooling where his head rested on the road. I was terrified of finding out whether he was breathing, but I still walked out into the road and leaned forwards to check.

I couldn’t tell. I couldn’t tell anything.

All I could think was that the last thing I said to my best friend was that he was a spineless twat.

HANNAH

I slide my hand into his. I’m not sure if he even notices.

AARON

It didn’t hit me until the hospital, when Dad came into the room and whispered something about Chris to Mum. She turned to me and held me, clinging to me, squeezing me as if I was the one who was never coming home. I held her back, let her cry silent, grateful tears into my shoulder, let her whisper to me that she loved me so much.

That was when I started to cry. There weren’t any thoughts, just feelings of loss and horror and grief, relief that my parents weren’t going through what Chris’s parents were, shame that I felt that way. Guilt drove me to cry harder and harder until I could barely breathe for sobbing and I was sick on the floor, but no one said anything, not my dad, not my mum, not even the nurse who quietly came and mopped it up and handed Mum one of those shiny steel bowls. I don’t know when they took me home.

During the police interview the next day I stared dully at the tabletop. I didn’t want to see the look in the officer’s eyes when I told her the truth.

“We were fighting.” I felt my dad go very still on the chair next to me. It was the first he’d heard of it.

“And…” The police officer’s voice was careful, neutral, non-committal.

“I didn’t… mean to.” The words seemed to fall out of my mouth, as if I had no control. “He was trying to get away and I was pulling him back…”

I closed my eyes, only to snap them open to avoid the memories waiting in the dark.

“You were pulling him back?”

I looked up at her then and I watched the way her jaw clenched as she looked back at me, waiting.

“I shouldn’t have let go.” I started crying so much that the interview was suspended and my father pulled me close and told me that he loved me. Told me that it wasn’t my fault, I wasn’t to blame. I didn’t believe him.

I was spared the funeral. When I couldn’t get out of the car in my new black suit, my dad simply turned round and drove home. But school was a distraction I thought I could handle. I was wrong. The sympathetic looks and hugs from the girls — except for Penny, who was absent; back pats from the boys; teachers ignoring the empty seat next to mine. But it was the gap in the morning registration, where his name should have been, that got to me most, reminding me of the space in my world that my best friend should have occupied.

At the end of the week I found Rav waiting for me by the main entrance. We’d been mates — the three of us.

“This week’s been hard,” he said.

I nodded.

“Want to come and get drunk with me and some of the lads?”

I did, and I got very, very drunk. Drunk enough that I could forget who I was for whole minutes at a time. Drunk enough to forget who my friends were and to end up sitting with the group of lads who hung out by the late-night supermarket near my house — lads that Chris and I had always been a little bit scared of.

Chris. No matter how much I drank, I could never forget Chris.

At least, not until I blacked out.

The next morning I woke up on the sofa in Rav’s room, my host telling me that I wasn’t allowed to be sick or his mum would find out what we’d been up to — not that I could remember any of it. For all the pain I was in, I realized that twelve hours had passed like twelve minutes. That night I didn’t need an invitation; I went down to the supermarket with enough money for the oldest lad — a guy called Smiffy, who was a Mark Grey of a man — to buy me a bottle of tequila and I drank the lot.

But I couldn’t pull the same stunt the next day, not on a Sunday.

The week passed by. Wake up. Remember. Go to school. Remember. Come home. Remember. Go to sleep. And repeat…

Somehow I’d managed to avoid Penny at school. We didn’t have many classes together and I’d turn up late and leave early in the ones we did share. Breaktimes I’d hide in the library, picking out a title at random and reading it for as long as I needed to lose myself, then putting it back on the shelf when the bell went. But Thursday night she rang my house.

“Ty. We need to talk.”

I told her I’d go to hers. The supermarket was between my house and Penny’s — it was seven o’clock and I wasn’t surprised to find Smiffy there with a couple of other lads. I handed him the twenty I’d taken from Dad’s wallet and asked him to buy me some vodka and cider. If I drunk enough before I went to Penny’s then she wouldn’t want to talk to me. I didn’t have much of a window, so I needed to drink fast and I cut the two together. Too focused on my own problems, I didn’t notice that Smiffy was looking for trouble when another group of kids headed into the supermarket.

There was a scuffle by the doors. It didn’t really register with me until the lad next to me yanked me up and said that Smiffy needed a hand. Not that I knew what to do with my hands, my brain was blurred with booze and I found myself stumbling into the back of one lad who turned and landed a crack to my browbone.

The world came into focus and it was red with remembering.

My guilt, my misery spilled out into violence and I plunged into the fray, grabbing a fistful of a T-shirt to land a punch so vicious I’d hear the crunch of my own bones, flooring one person to start on the next. Everything in me was unleashed, all the hatred I had for myself… I wanted to hurt, lashing out with abandon, incapable of feeling the brutal blows landed in retaliation. The more I fought, the less I seemed to feel, driving me to dismay, spurring me on, desperate to find a way to feel the pain I deserved.

Senseless with grief, I ended up laying in to one of our own.

“What the—?” Smiffy held his nose, arm up to block my next punch, missing the kick I let fly. He doubled over, grabbing me on his way to the floor. I was rabid, flying with my fists, my feet and my head, all of them making contact with something as everyone piled in to try and stop me, to calm me down. Someone shouted out that I was bleeding, but I didn’t care and I heard someone else scream — it could have been me — or the guy I’d just hammered in the nuts.

“Stop it!”

It was a girl’s voice and the bodies surrounding me started peeling back as the person who shouted pushed through.

“TY!” There was blood smeared across one of my eyes and I was having problems focusing through the other. But I would have recognized Penny anywhere. She’d grown bored of waiting and, when I didn’t answer my mobile, she’d set off to find me.

When I opened my mouth to speak something came out, blood and part of a tooth.

Penny called my parents, who drove me to hospital. I was concussed. Badly bruised. One of my teeth was chipped and I had to have stitches in a gash that ran the length of my left forearm and a cut in my jaw where you could see the bone. Although my nose remained miraculously unbroken, I’d broken my little toe and fractured one of my fingers.

No one was particularly pleased with the amount of alcohol I’d consumed but the threats to pump my stomach were just that.

The whole time my mum remained calm, listening to the painkiller doses, writing down how often she needed to wake me because of the concussion and any symptoms that signalled an immediate return to A&E. Dad cried in the car on the way back. He didn’t want me to see him, but I saw his shoulders shake and noticed Mum take her hand from the gearstick and rest it on his knee.

The next day was spent in pain. And shame. My parents sat with me, talking to me, telling me that they loved me and that I couldn’t punish myself like this.

“Why not?” I whispered. “I deserve it.”

Mum tilted my chin up, forcing me to look at her.

“We don’t.” Mum kissed my forehead, her hand on Dad’s. I leaned into her and Dad hugged us both so hard that I worried he would pop a stitch.

HANNAH

The hand that is not in Aaron’s has found its way to the bump. I think about the child I don’t yet know and I get an inkling that maybe I have more in common with Aaron’s parents than with him.

AARON

Penny was waiting for me in the library on Monday. She took in the damage as I sat down — the yellowing bruise around my eye, the patch of stubble where I couldn’t shave around the stitches on my jaw, the taped fingers.

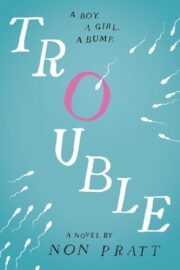

"Trouble" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Trouble". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Trouble" друзьям в соцсетях.