Kieran turned from the sink where he was rinsing a couple of wine glasses under the tap. ‘I didn’t realise you were so tired.’ He frowned. ‘I suppose I keep forgetting you are new at the job.’ He smiled. ‘You are so good with people, Abi, I’ve been taking advantage of your good nature without realising it.’

She shrugged, fighting the reflex reaction of denying that she couldn’t cope. ‘I suppose it does take a while to get used to the hours. And the misery and the deprivation and the hostility. No peace for the wicked!’ She forced herself to smile at her own feeble attempt at a joke. Her throat was sore and she felt shivery as he put a glass down before her and poured out the wine.

He stood in front of her for a moment, anxiously studying her face then he reached out and put his hands on her shoulders. ‘I’m sorry, Abi. I’ve been selfish. I’ll take over the home visits for a bit. Of course I will. I wanted you to experience the realities of this job first hand as soon as possible. I wanted to make sure you understood what the church is all about. I thought if you saw the worst at once, in a sense it could only get better. That was stupid of me. I should have seen it was all too much for you.’ He paused. Then he leaned across and dropped a small dry kiss on her forehead. It was avuncular, she told herself firmly, suppressing a quick shiver of pleasure. His action had conveyed nothing more than affectionate sympathy.

Which didn’t in the event last long. Within a few days he had gently suggested she resume her duties and she was working as hard as before.

Wednesday, Abi had discovered, was the day the curate visited the sick and lonely. As she found herself wearily climbing the stairs of a six-storey concrete low-rise off a shabby noisy street half coned off for repairs, she realised this would be her third visit of the day, her fourth in a month to this particular address. She wrinkled her nose at the unedifying odours coming from the suspiciously damp corners on the landings and turned at last to the final flight.

Ethel Barryman’s door was blistered and scarred. She could see from the marks that the lock had been replaced at least twice. There was no bell. She raised her hand and knocked sharply, wincing as her knuckles met the roughened wood. The door opened so quickly she wondered if the old lady had been standing on the other side, waiting for her.

‘Come in, dear.’ Ethel was small, wizened and frail, her face a transparent white, her hair thin, the remains of an ancient perm snaking through the faded hennaed strands.

In the sparsely furnished living room the table was laid with a white lace cloth on which stood a teapot, a plate of biscuits and two porcelain cups without saucers – those had been smashed by the last pair of thugs who had broken in, seemingly just for the sheer joy of doing it as there had been so little to steal. ‘For after.’ The old lady smiled.

Abi nodded. ‘Is your granddaughter still doing your shopping?’ She unslung her bag from her shoulder, in it the tools of her trade: small brass candlestick, candle, little cross on a base. Little box containing the necessities for Communion.

‘She’s good to me,’ Ethel nodded. ‘Comes twice a week. Sometimes more. And there’s Angela, downstairs. She gives me a hand when the pain is bad.’ Her eyes filled with tears and she turned away sharply. ‘Silly bugger me! Think I’d be used to it, by now.’

Abi smiled gently. ‘No word yet about a place at the hospice?’ She didn’t need the shaken head to know the answer. ‘Shall we pray together?’ She could feel her hands heating up. The urge to lay them on the woman was overwhelming. The need to draw away the pain, to replace it with gentle cool healing.

She laid out the little cruet, containers of bread and wine and lit the candle. Then she moved over to rest her hands on the old lady’s head.

When the short service was over it was Abi who made the tea. She glanced at Ethel with a smile. The old lady had relaxed. The pain had gone from her eyes. ‘You’re a good girl, Abi,’ Ethel said after a while. ‘I still can’t bring myself to call you vicar!’ She looked up at Abi, her face full of lively humour. ‘Come and see me again soon.’

‘You know I will.’ Abi dropped a kiss on her head as she left. From the doorway she turned and raised a hand in blessing.

The next day Kier told her that Ethel Barryman was dead. Her granddaughter had found her in the chair where Abi had left her.

Abi stared at him in shock. ‘But she was better! She was cheerful.’

‘You gave her Communion?’

Abi nodded.

‘Then you did your best. It’s part of your job, Abi. You’ll get used to it.’ He patted her arm before opening a file on his desk, pulling out another address. ‘Go and see this woman next. Molly Cathcart. Constantly whingeing. Real fuss pot. Wants attention all the time.’ He groaned.

‘But Ethel -’ Abi was still thinking about the old lady’s gentle smile. ‘Can I take her funeral, Kier? I’d like to.’

He shrugged. ‘I’ll see what the family thinks. They may prefer me.’

She didn’t argue. What was the point.

Abi met Sandra in town one Monday a couple of weeks later. Mondays were supposed to be Abi’s day off and she had promised herself time for a trip to visit Marks & Spencer. They talked casually for a few minutes on the pavement then drifted across Sidney Street, dodging through the crowds to find a coffee shop. Sandra ordered coffee and teacakes for both of them then she sat back and looked at Abi closely. ‘So, how are you coping up at Chateau Scott?’

Abi smiled uncomfortably. ‘All right, I think. It’s hard work.’

‘You’ve lost weight.’

Abi nodded. ‘I often don’t have time for meals. So this is a special treat. Thank you.’

‘I suppose he’s making you chase around all the hopeless cases?’

Abi frowned. ‘No-one is hopeless,’ she said uncertainly.

‘You knew he had a curate before, didn’t you?’

Abi nodded again. ‘Curates move on.’

‘Luke had a nervous breakdown. Overwork.’

That had explained the atmosphere in the flat. Abi eyed Sandra thoughtfully.

‘He’s a bit of a control freak, Kieran,’ Sandra went on. ‘Things have to be done his way. But I expect you’ve discovered that. I suspect you are a tougher cookie than poor old Luke.’

Abi sighed. She had prayed for the young man and blessed him, filled the rooms with flowers and the sad echoes had gone. He had gone on to a parish the other end of the country and she had heard through the grapevine that he was happier now that he was no longer working with Kier. She had been told only that they had not been compatible; not why. ‘Yes,’ she said thoughtfully, ‘I expect I am a lot tougher cookie than him.’

‘I didn’t mean that in a bad way.’ Glancing up, Sandra smiled apologetically. ‘I just thought I should drop a hint.’ She took a deep breath. ‘I heard you’d been to visit Molly Cathcart.’

Abi nodded. The coffee arrived and there was a pause as they each took a sip.

‘She’s much better than she was,’ Sandra went on.

Abi nodded. ‘I felt so sorry for her. She’s in so much pain with her rheumatism, and she’s all alone in that small flat.’

‘You prayed with her, I hear.’

Abi nodded. ‘That’s part of the job.’ She helped herself to a toasted teacake and reached for the butter.

‘And you gave her healing.’

Something in Sandra’s tone made Abi look up. Sandra shrugged. ‘Be careful, Abi. There are people round here who pretty much equate healing with witchcraft. Kier is one of them.’

Abi stared at her in astonishment. ‘But the ministry of healing is part of the job,’ she protested.

‘Not in Kier’s book.’

Of course. She should have guessed. Besides the heavy workload dumped fairly and squarely on her shoulders, the reality of confronting, time after time, parishioners who felt that a female vicar was something between the short end of the wedge, a witch and Satan’s little helper had hit her hard. It just hadn’t occurred to her that Kier might be one of them.

The voice of one of her lecturers at college echoed in her head for a moment. ‘Abi, remember, although more than half of all the clergy being ordained today are women, there are still a lot of people out there who are suspicious of them, not least a good proportion of the other clergy!’ How right he had been! She thought back over the first months of her curacy here and she sighed. It was all so much harder than she had ever imagined it would be.

She confronted Kier that evening. ‘Why didn’t you tell me that you disapproved of healing?’

He glanced up at her. She had cornered him this time, walking into the study where he was seated before his desk. The room was warm, lit by the last of the sun and its light was catching his hair, turning it a deep coppery red. He looked up at her and laid down his pen, carefully aligning it with his blotter. The computer was on a side table on the far side of the room. Beside it piles of letters and papers were arranged in neat sequences, graded by size. ‘It did not occur to me that it would be something you would attempt,’ he said carefully. ‘When I began to receive reports, I didn’t believe it at first. I assumed that people were misinterpreting your zeal for prayer.’

‘Has someone complained?’

He nodded. ‘I’m afraid so. It has reinforced the natural aversion some parishioners still feel towards a female priest. I’m sorry, Abi. I should have mentioned it. I just hoped you would realise that it was not appropriate.’

‘But it is appropriate! It is what Jesus taught us to do. It is what I learned at college. I was encouraged to do it!’ She was furious.

‘People round here don’t like it, Abi.’

‘Ethel liked it. So does Molly Cathcart. It has helped her. She was healed. She has been outside for the first time in months.’

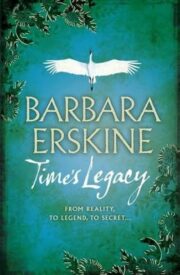

"Time’s Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Time’s Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Time’s Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.