Yeah, maybe. “I want to go after him so bad.” She sighed and hugged her sister-in-law briefly with one arm.

“I know, sweetie. But nobody knows where he is. It’s best to stay put—for now,” she ended hastily when Leslie frowned.

Lorelei was probably right, but she hadn’t seen the look on his face when he’d been talking in Ukrainian. Peter had gone so cold and detached that he’d looked like a marble statue.

Which meant he was really hurting.

Knowing that pushed the disappointment over losing the bet right out of her mind. There were more important things to worry about now. Things like Peter handling his dad’s death alone.

And things like how she’d told him that she loved him.

She hadn’t missed that fact. As much as she might like to lie and pretend that she didn’t remember declaring her love for him, it just wasn’t true. Leslie remembered all right. It had come back to her when she’d thrown his T-shirt at him. She just wasn’t going to remind him.

When he returned she was just going to hug him hard and pretend like she’d never uttered such nonsense. Maybe he hadn’t even heard her. There was always that possibility. If he never heard her then it wouldn’t even be an issue. They could just go on.

Yeah, that would be great.

Wasn’t going to happen, though. She knew Peter and he was going to pick at her, poking and prodding until she lost her shit and told him everything he wanted to know—and a whole lot of what he didn’t.

Chapter Twenty-Two

PETER STEPPED OUT from the shabby corner Dunkin’ Donuts into the freezing Philadelphia air and huddled into his leather coat, one hand cradling his coffee. The heavy gray sky that was just starting to snow perfectly matched his mood.

He’d been in the city for almost a week handling the details of his father’s death. Not that there was much to handle, truthfully. Mostly he was there out of a sense of obligation and to see that he was buried properly. It was the first time since he’d turned eighteen that he’d been back to the city for anything other than a ball game.

It was hard.

Flipping up the collar of his coat, Peter shoved his free hand in a front pocket and glanced around at the urban decay of South Philly. He had decided to park his rental car in a more stable neighborhood and walk the rest of the way to the house where he’d grown up; a long stroll was preferable to a car-jacking and he wasn’t concerned about being mugged. He knew how to handle himself. Along the way he passed crumbling structures covered in colorful graffiti. One of the dilapidated brick buildings had a two-story mural of a smiling Jamaican woman at home in her native land, lush palms behind her and a basket full of plump sweet potatoes.

The juxtaposition of such hope, pride, and beauty amidst such poverty and despair was beyond jarring. But it spoke to the heart of the people that made their home there. In a land that was supposed to take care of its own, they were living in a third-world country. It wasn’t right. It wasn’t even close to right. Still, they kept the hope. They saw beauty.

They were his people.

He hadn’t helped his father.

The thought came at him from left field, catching him unaware. It wasn’t for a lack of trying. Considering his pop was the only family he’d had, Peter had gone to the mat for him and tried to get him clean, tried to get him help. But Viktor Kowalskin had wanted nothing more than to kill himself with drink.

At some point in the last two years, Peter had just quit trying. And now his pop was dead from liver failure and he felt guilty. Like he should have tried harder. Like he shouldn’t have given up on his old man. But what was he supposed to do? The man was an abusive drunk, unwilling to change. And now he was gone.

There was a part of him, although tiny, that felt relieved. It was over. Now he could move forward without this always around his neck, weighing him down. It was a crappy, selfish feeling and he knew it. But he was just so tired of fighting against everything. It had made him weary.

He’d fought against the inevitable and lost. His pop, his eye disease, Leslie. In the end, no matter how much of a fight he’d put up, it hadn’t been enough.

His life felt a lot like the wreckage and rubble that he was strolling through.

He crossed the street as a low-rider Buick painted in gray primer cruised down the street past him very slowly. A group of young thugs were huddled inside the car, giving him a very thorough shakedown. Any other person would be perturbed by the territorial display.

But they weren’t Peter.

His body posture changed and he morphed into the kid who’d known these streets, who’d known how to act. He wasn’t worried. Hunching his shoulders, he continued walking, sipping casually from his to-go cup of coffee.

The car sped up suddenly, the juveniles shouting obscenities at him as they whipped past and threw a beer can. But then they rounded a corner and headed out of sight, the sound of the souped-up Buick fading in the distance.

Peter took a left as he got closer to his old neighborhood and felt anxiety twist painfully in his gut. A pit bull on a chain rushed him from the right, barking hard and slobbering. The clearly underfed dog was crazy-eyed. Reaching into his pocket, he pulled out the last of his breakfast burrito and unwrapped it. Then he tossed it to the foamy-mouthed canine. “Here, dog. Eat.” He knew all too well what it was like to starve in this place.

The busted sign declaring that he’d arrived at his designated street came into view as a damp, frigid wind blew a gust hard enough to have him sucking in a breath. Damn, that was cold. He’d forgotten how different Philly winters were from Denver. The cold here was wet and heavy and had a way of seeping right into the bones, chilling a person to the core.

Turning off the main road into a small, sad-looking ethnic neighborhood, Peter scanned the barely-habitable shacks, noticing a curtain flutter in one of them as he went by. It wasn’t every day that these people had a random guy walking in their hood. And if they did it was normally a cause for concern. If it was him, he’d be peeking out his window wanting to know who the hell was out there too. It was a matter of safety.

He didn’t have to be there. Didn’t have to go back to his roots. But after avoiding it for almost a week by busying himself with all the legal hoopla and logistics of burying his old man, he’d finally accepted that he couldn’t stay away. Who he was now stemmed from growing up in this place.

The shacks he walked past were really worn-down, buckling old bungalows. Nothing more than rectangles with front steps, the tiny houses butted right up to the street. There was no grass, no green. Lawns were for rich people.

His old place came into view down the road as the memory of Leslie asking him about food came to mind. That woman saw everything—things about himself that he didn’t even recognize. It was more than a little scary. And now she said she was in love with him.

It ruined everything.

Peter didn’t want to be loved, or so he told himself as he strolled down his old street. The heavy sky kicked into gear and snow started to fall steadily now, covering the ground in minutes. He just kept on walking, taking reassuring sips of steaming coffee.

What the hell was he supposed to do with love?

Sex, he understood. Passion, desire, lust—those emotions he got. But love? About that, he didn’t know a fucking thing. All he knew was that it always screwed everything up. His mother leaving his pop for another man under the premise of “love” was his only point of reference, and it was a pretty shitty one.

Nobody loved him.

And that was okay. It was a flawed concept anyway. So why did Leslie have to go and mess it all up by claiming to be in love with him? They were good the way they were. Two independent people with a ton of sexual chemistry. That he understood. It made sense. Besides, even if she was in love with him now, it would only be a matter of time before she realized he wasn’t worth it.

She was a princess. He was this.

Peter shook his head, lips pressed together tightly as snowflakes clung to his dark hair and he approached his childhood home. He could see it up ahead and his gut went greasy, unsettled. The squat shack was literally falling down. Its roof was bowed and one of the back corners drooped, leaning listlessly to the side like the foundation had washed out from under it. The gray paint was mostly peeled and some of the windows were boarded up with a combination of cardboard and duct tape.

Pretty much looked the same as it always had.

Still two houses away, Peter whipped his head around when a front door nearby creaked open. Bracing himself, his body instantly relaxed when he saw who stepped out.

“Hey, Mrs. Petrov,” he greeted in Ukrainian, his breath releasing white puffs into the air. He couldn’t believe the old lady was still alive. She’d been ancient when he was eighteen. It was her grandson Ivan who’d called him Halloween night. Peter had assumed she’d died ages ago. Tough old Slavic bird.

“Is that you, Peter Kowalskin?” Her voice was paper thin and raspy with age. He could still remember the way it used to get all shrill when she yelled at him and some of the other neighbor kids, including Ivan, for stealing fireworks and setting them off in the middle of the street.

Peter smiled at the memory and strolled over to give her a kiss on each of her frail cheeks. Her faded blue eyes crinkled and she swatted a hand at him, chiding, “You stay away too long, boy. But look at you all grown and strong and handsome. Doing well for yourself. You came back for him,” she ended, not asking but rather making a statement.

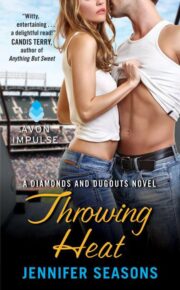

"Throwing Heat" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Throwing Heat". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Throwing Heat" друзьям в соцсетях.