He was wild to see her; there was no denying the truth of it. But it was also true that he feared to see her. The memory of that moment in the parsonage, when her presence and his desire’s imaginings had caused him to doubt his reason, had been a continual torment and tease. The scene had intruded on his every thought and accompanied his every action. One moment, the remembered delight would be such that he would give much to be caught up so again, and the next, when the reality of the situation reasserted itself, he swore that he would give anything not to be. Darcy clenched his fists. This mad swinging of his thoughts and desires was becoming intolerable! His resolve had melted in the candescence of her eyes. His self-physic of duty and busyness had been an utter failure. Is there no means of quenching this fascination?

The only response to his plea was the sudden, shrill call of one of the peacocks allowed to roam the park. On its heels followed a faint “Darcy!” from the house. Looking in that direction, Darcy spied Fitzwilliam at the opposite end of the garden, striding purposefully toward him. Come to plague him, most like. But as Richard advanced, something he had said earlier that morning teased Darcy’s memory. What had it been? Something about having had a surfeit of Collins? Darcy seized upon the thought. Might that be the solution to his obsession with Elizabeth?

“Fitz! It is time to be off! What the devil are you doing out here?” Richard demanded querulously as he came upon him. “Why did you abandon me to the old she-dragon? Fitz!” He addressed him again when he got no reply. “And what the devil are you smiling at?”

It was indeed a fine Easter morning. So mild was the weather and so light the breeze that Lady Catherine consented to Darcy’s request that the calash of the barouche be let down. The beauties of the Kent countryside, thus displayed in their full glory, were duly observed under the lady’s express direction and commentary, but Darcy never heard her during the sojourn to Hunsford, nor he suspected, did his cousin. This was of no consequence, for an unfocused stare and an occasional nod were all Her Ladyship expected or desired from her nephews. Any more fervid a response would have given rise to a suspicion of “artistic” tendencies, which the lady deplored almost as much as “enthusiast” ones in men of rank.

The distance to Hunsford by carriage was not long, but it was obvious from the agitated demeanor of its rector as he fluttered about the threshold that they were late. Since Darcy’s turn in Rosings’s garden had hardly delayed their departure, it was plain that Lady Catherine’s timetable had been designed with a grand entrance in mind. Members of the elevated strata of the local gentry stood with Mr. and Mrs. Collins outside the church doors in order to greet Her Ladyship and her distinguished nephews, but Elizabeth was not among them. Darcy tensed as the barouche swayed to a stop and it became apparent that neither was she to be seen within the threshold of the church. Chagrined, he glanced at Fitzwilliam, who was scowling with annoyance, first at his aunt and then at the crowd gathered on the church step.

“Too late!” Fitzwilliam grumbled under his breath as one of Rosings’s scarlet-clad servants hurried to open the barouche’s door. “And a bloody gauntlet to run as well!” Once the door was opened, he bounded out of the equipage, forgetting his duty to his aunt for the length of two strides before Darcy caught his arm. “Richard!” he hissed to him. Fitzwilliam stopped short, a question on his lips that Darcy answered with a silent cock of his head. “Oh, good Lord!” Fitzwilliam whispered fearfully and, pasting a smile on his face, stepped back to the carriage and offered his waiting aunt his hand down.

“I shall write to your mother, Fitzwilliam,” Lady Catherine announced as she took his hand and descended from the barouche, her eye sharply inspecting his now blanching countenance, “and inform her of your unusual behavior. Further, I will advise that she read it to His Lordship.”

“My Lady” — Fitzwilliam bridled — “I beg you to believe that I haven’t turned Methodist.”

“I should say not!” interrupted his aunt. “You were baptized in the Church of England, sir, of which fact I was a material witness, and there is an end to it! Now, no more of such nonsense!” She took his arm and nodded toward the church door. In seething obedience, Fitzwilliam escorted her forward.

Impatient to be past Richard’s aptly labeled “gauntlet,” Darcy turned to his female cousin and extended his hand. Anne’s ephemeral touch drifted down upon his forearm for only a few seconds and, to his surprise, was quickly withdrawn when she gained the ground. He looked down at her curiously, but her gaze was averted from him, hidden by the brim and gathered flowers of her bonnet. It came to him suddenly then that she had not spoken a single word during their breakfast or sojourn, nor had he observed her attend to anything but the passing scenery or her own glove-clad hands, which had lain clasped in her lap. Even now she said nothing, merely stood like Lot’s wife where she had alighted from the carriage, waiting.

“Shall we walk, Anne?” he asked evenly. The bonnet moved slowly up and down, and Darcy almost thought he heard a sigh as he once more offered his arm to his cousin. Two thin fingertips came to rest on his blue coat sleeve, but he knew so only by sight; their weight was undetectable. He started forward slowly, expecting a reticence from her that would require he coax her on, but she responded to his signal and walked in unison with him to the church door. Still without looking at him, she paused, anticipating his need to shift his walking stick to his other hand and remove his hat at the threshold. He nodded curtly to the assemblage there, forestalling any attempted conversation, and led her inside.

The sudden, cool dimness of the entryway beneath the bell tower was a welcome respite from the glare of public scrutiny, but Anne seemed to shrink even further within herself as a shiver caused the fingers pressed so lightly on his arm to tremble. He looked sharply down, maneuvering to catch a glimpse of her face, but the semidarkness and her bonnet still shielded her from him and for the first time Darcy felt some concern for his cousin. Something was wrong, that was very evident, but what could it be? Sudden shame flooded him as he realized that he could not possibly guess her trouble, for he had never taken even a passing interest in her concerns. She had always been merely Anne, his “unintended,” his sickly, female cousin: a pitiable thing with which any healthy, young male would have had little to do. And, to his dishonor, he had not.

Hunsford Church was a respectable edifice. The structure itself was not a grand one, nor the nave a particularly long one. But it might as well have been Westminister for the time it seemed to require Darcy to escort his cousin to the de Bourgh pew and Lady Catherine’s side. Relieved at last to have completed the promenade, he handed Anne into the box, and was free, so he thought, to blend himself into the rest of the congregation as he searched it for Elizabeth’s profile. Doubtless, he thought as he set aside his walking stick and hat, Richard had already found her and he needed only determine in which direction the Rudesby was gawking. But a surreptitious glance past Anne to Fitzwilliam on her other side told Darcy that, far from engaging in a nave-wide flirtation with Elizabeth, his cousin’s habitual good humor had quite fled. In all Darcy’s past experience of Lady Catherine, it was only his father who had ever been able to stand against her and even bring her to some semblance of womanly reserve. Since his passing, those more feminine aspects of her nature had been overthrown completely by her imperious disregard of all but her own opinions, of which Richard now suffered the brunt of her latest rendition.

A flurry of movement and song from the rear of the sanctuary brought the congregation to its feet. From habit, Darcy’s limbs also heeded the call, and he rose even while he discarded the puzzles of his cousins to take up the more intriguing one of finding Elizabeth in the crowd. Thankful again for his height, he began to search the meadow of flowered and fruited bonnets for the one that sheltered her glory from the casual eye, but at that moment the small boys’ choir began the processional, their voices — only occasionally on key but earnest and clear — echoing against the ancient walls. Darcy’s gaze flicked down the aisle. Behind them, in stately stride, came Mr. Collins, his white surplice starched to within an inch of its life and his eyes cast reverently heavenward. So he proceeded until he drew even with the de Bourgh pew, at which point he startled both Darcy and Fitzwilliam with a sharp turn in their direction and bowed deeply to each member of the family of his noble patroness. It was just as the ridiculous man was rising from these embarrassing flatteries that Darcy saw behind him and across the aisle a flash of blue belonging to the ribbon of a straw bonnet decked with freshly picked lilies of the valley. As the brim came up, a pair of velvet brown eyes appeared above a pert nose and beguiling lips held back from exposing their owner’s amusement by delicate, glove-clad fingertips. The sight was pure enchantment, and he was more than disposed to allow it to have its way.

Filled now with the sight of her cousin Mr. Collins, Elizabeth’s lively eyes danced with the diversion. But not content with beholding his fawning attentions, her eyes swept up to observe his effect on others and, to Darcy’s surprise, she began their examination with his own face. The expectancy in her eyes and the sweet curve of her lips shot through him like a bolt, pinning his senses to the moment, and in that eternal second he could only wait and watch for what would come. A puzzled frown lightly touched her countenance. Although it allowed him some respite, her bewildered regard excited his curiosity. What intrigued her?

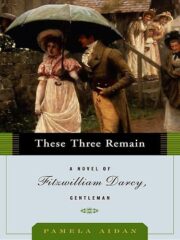

"These Three Remain" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "These Three Remain". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "These Three Remain" друзьям в соцсетях.