“Ahem.” He cleared his throat and straightened his waistcoat, giving his friend opportunity to recover himself. When Bingley’s head came up, Darcy pushed the note back across the desk. “It will do. Shall it be sent?”

“Yes, by all means,” Bingley returned with a quick, faint grin. “I would not wish to accept the wrong invitations.” He took up the note and slowly creased it into precise thirds as Darcy looked on, dismayed at his quip. Did Charles truly have so little faith in his own judgment? Had Darcy’s attempt to act his mentor convinced him instead that it was safer to put his life in the hands of others he held wiser than himself ? If this was so, he had done Bingley a further wrong.

“You need only take young Hinchcliffe’s recommendations as suggestions, Charles. The final word is yours in this as in all your dealings. If you should find yourself somewhere you discover you would rather not be, you will know what to do. You have ever landed on your feet in any social occasion in which I have observed you.”

“Is that so?” Bingley’s face brightened tentatively. “A compliment, Darcy?” His uncertainty cut Darcy to the quick. When had he fallen into the pattern of treating his friend as less than his equal? How had the man borne his condescension?

“No, the truth, Charles.” He faced him squarely. “If more of humanity was possessed of your innate good nature, your ability to make those around you comfortable and well disposed toward the world, Society would not be half the gauntlet that it is.” He paused to see the effect of his words. The brightness in Bingley’s face had gone a bit flush, but the grin on his lips assured Darcy it was from pleasure rather than anger or embarrassment. “Lord knows, I could profit from some of your talent.” Darcy sighed both for the truth of his confession and for his relief that Bingley was coming back to himself. “Perhaps I should apply to you for lessons!”

“Lessons!” Bingley laughed and rose from his seat. “Shall the master and student change places?”

“No.” Darcy shook his head and stood. “You are graduated, Bingley! I have encouraged you, wrongly, to lag behind in the classroom. I would rather we were friends coming to each other’s aid.” He extended his hand, which Bingley, though surprised, took readily. “Equals standing ready to assist each other along the way.”

“Of course, Darcy, of course!” Bingley beamed at him.

Darcy nodded and strengthened his grip on Bingley’s hand. “I overstepped the bounds, my friend. What I can rectify, I shall. I promise you.”

A knock at his study door a week later brought Darcy’s head up from his book and that of his hound from close contemplation of that activity. Trafalgar rose from his station at his master’s side and padded over to the door, his nails clicking against the polished wood floor between the islands of carpet laid about the room. As Darcy watched, the dog reared on his haunches against the door and batted expertly at the knob until the latch disengaged, then jumped back to nose open the portal. A happy whine from deep within the animal’s chest told Darcy who would soon appear.

“Trafalgar has become quite the gentleman, Fitzwilliam.” Georgiana leaned down to stroke the broad, silky brow above liquid eyes turned to her in hope.

“A highly discriminating one, though.” Darcy shook his head at his sister’s fawning supplicant as he rose to greet her. “He will do the pretty only for those of whom he approves. You, my girl, merely happen to be one of that select party.”

Georgiana laughed and, with one last pat, straightened. “I have come to inform you that Miss Avery has gone, and you may leave the safety of your den for other parts of the house.”

Darcy looked askance at her. “Do you mean to imply that I have gone to ground?”

“I cannot help but notice that you have managed to be absent or to find pressing business in here every time Miss Avery calls.” She smiled at him as she came to his side. “Even so, she thinks you are the perfect gentleman.”

“Georgiana!”

“And that I am the perfect young lady.” She sighed. “It is a bit difficult, is it not, to be so worshiped?”

Darcy took her arm and led her to a settee. “Is it very hard to receive her? I know I have imposed upon you abominably.”

“No, Brother, not ‘abominably.’ Miss Avery is a very different sort of friend but not an unwelcome one.” She laid her head on his shoulder. “Fitzwilliam, she is so crushed by the weight of her brother’s scorn one moment and his dismissal of her existence the next. His opinion of her she takes as the world’s. It is no wonder that she is so timid. When I think —” She stopped and pressed her face into his shoulder.

“When you think what, sweetling?” he prompted, brushing her curls lightly.

“When I think how kind you have always been to me, encouraging me…Oh, thank you, Fitzwilliam!”

He had turned and was halfway back to his desk when it suddenly occurred to him. He turned back. “Georgiana, are you still of a mind to subscribe to that society?”

“The Society for Returning Young Women to Their Friends in the Country?” He nodded. “Oh, yes, Fitzwilliam! Have I your permission?”

“Allow me to look into it further, and if I am satisfied, you may direct Hinchcliffe to disburse what sums you deem appropriate.” His sister, her eyes shining, made to rise, but he held up his hands. “No, do not thank me. I have been remiss in this as well as in my own charitable concerns. Truly, I have done nothing more than authorize the continued maintenance of our father’s charities. Neither have I looked beyond Hinchcliffe’s assurances that their boards were respectable and their books balanced.” He looked away from the bright warmth and wonder in Georgiana’s face, his jaw working as he summoned up the words. “I have held myself aloof from such things. That,” he confessed in a low voice, “will no longer do.”

Trafalgar looked after Georgiana as she left the room but appeared to decide against an impulse to follow, turning back to his master instead. Darcy returned his solemn regard. “Well, perfect gentlemen are we?” Trafalgar yawned broadly and then snorted, shaking his head before laying it back down upon crossed paws. “Quite so,” Darcy agreed and rose.

Walking slowly to the window, he leaned against the frame and looked down onto the square. Miss Avery held him to be the perfect gentleman, did she? A drop of rain tapped against the window and then another. Miss Avery had narrowly escaped a wetting, or conversely, he and his sister had narrowly escaped an entire afternoon harboring her from the weather. He traced the passage of a drop as it flowed down the pane. He must be objective, dispassionate, if he was to sort it all out. It had been nearly a month since Hunsford. He ought to be capable of a dispassionate objectivity by now.

What had been Elizabeth’s initial impression of him? From their first encounter at the assembly in Meryton, when he had uttered that graceless dismissal of her, she had set him down as a figure of amusement. He had done no less than to prove her right. Like a pompous fool, he had held himself apart, strutting about the social circles of Hertfordshire with nothing better to do than look down a very ungentlemanlike nose at everyone.

How could it be that he, who had the best of examples before him and the most solemn of intentions, had come to this? Somehow, in the long years of his childhood and youth, he had gone off course, taken on the trappings and attitudes that made him seem now a most unlikable man and a stranger to his own heart.

Trafalgar’s whine and hard nudge against his hand brought the room back into focus. “Yes, Monster.” He stroked the animal’s head. “All is well, at least where you are concerned,” he amended.

With a low, rumbling sound, Trafalgar pressed his head against Darcy’s knee.

“Yes, I know. The questions remain.” He stroked the silky ears again. “But the answer would be more than I wish to contemplate.”

With a grimace, he ceased stroking Trafalgar’s ears, ignoring the nudge and whimper. It was impossible! Even could he bring himself to petition for it, there was no pretext under which he could seek out Elizabeth, nor were their paths ever likely to cross. Nevertheless, the idea was novel enough to force him to his feet. If it were possible, could she forgive him?

His imagination brought her to him so swiftly he almost started. Admire and love her, he had claimed. How could he possibly do so when he had misread her every action, misconstrued her every word? The extent of his self-deception was astounding! He had presumed himself in possession of her mind and heart when, had he been questioned, he could not have stated with any certainty what she thought or felt upon any subject of importance or what she most desired in life.

Love her? No, he had dallied during these many weeks in his rooms at Pemberley, London, and Kent with an imaginary Elizabeth of his own design, woven from the colored threads of his own desires. In such a state he had gone to her, and she, with no money or prospects of her own, had roundly refused him — refused him, even with so much at stake. The consequences Elizabeth had embraced rather than trust her future to his care loomed more solidly before him than had they heretofore. What kind of woman would do so?

Turning his back to the window, Darcy crossed his arms over his chest, presenting such a picture of concentrated intent that Trafalgar raised his head from his paws, his body tensed in hopeful readiness as his master once more took up the pace of the room. He had come thus far to find an answer, a way through to some resolution of this shocking month of self-revelation, and he was determined to bring all his faculties to bear on the question. What had he to offer as proof of his contrition? Nothing! Certainly nothing that a woman of such principle as she exhibited would be inclined to accept or respect! For a moment he stood there, helpless, before it struck him. The road to becoming a man worthy of the respect of such a woman began in seeing the world and measuring himself through other eyes, eyes that were sensitive to his defects and shortcomings.

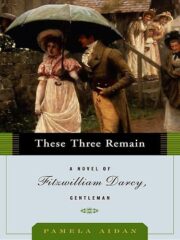

"These Three Remain" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "These Three Remain". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "These Three Remain" друзьям в соцсетях.