“Eh bien!” Léonie’s heart beat fast, but she maintained her outward composure. “Enlighten me, madame! What does Paris know?”

“That you are a base-born child of the Saint-Vire, my child. And we—nous autres—laugh to see Avon all unconsciously harbouring a daughter of his dearest enemy!”

Léonie was as white as her ruffle.

“You lie!”

Madame laughed tauntingly.

“Ask your fine father if I lie!” She gathered her skirts about her and made a gesture of disdain. “Avon must know soon, and then what comes to you? Little fool, best leave him now while you may do so of your own choice!” She was gone on the word, leaving Léonie to stand alone in the salon, her hands clasped together tightly, her face set and rigid.

Gradually she relaxed her taut muscles, and sank down again upon the couch, trembling. Her impulse was to seek shelter at Avon’s side, but she restrained herself, and stayed where she was. At first she was incredulous of Madame de Verchoureux’s pronouncement, but little by little she came to see the probability of the story’s truth. Saint-Vire’s attempt to kidnap her was thus explained, as was also the interest he had always taken in her. Sick disgust rose in her.

“Bon Dieu, what a father I have!” she said viciously. “Pig-person! Bah!”

Disgust gave way to a feeling of horror, and of fright. If Madame de Verchoureux had spoken the truth, Léonie could see the old loneliness stretching ahead, for it was clearly unthinkable that such a one as Avon could marry, or even adopt, a girl of her birth. He came of the nobility; she felt herself to be of mongrel blood. Lax he might be, but Léonie knew that if he married her he would disgrace the ancient name he bore. Those who knew him said that he would count no cost, but Léonie would count the cost for him, and because she loved him, because he was her seigneur, she would sacrifice everything sooner than drag him down in the eyes of his world.

She bit hard on her lip; it was better by far to think herself of peasant blood than a bastard daughter of Saint-Vire. Her world was toppling about her ears, but she rose up, and went back into the ballroom.

Avon came to her soon, and gave her his arm.

“I believe you are tired, my infant. We will find Lady Fanny.”

Léonie tucked her hand in his arm, and gave a little sigh.

“Monseigneur, let us go, and leave Lady Fanny, and Rupert. I do not want them.”

“Very well, infant.” Avon beckoned to Rupert across the room, and when he came to them, said languidly: “I am taking the child home, Rupert. Oblige me by waiting to escort Fanny.”

“I’ll take Léonie home,” offered Rupert with alacrity. “Fanny won’t come away for hours!”

“That is why I am leaving you to look to her,” said his Grace. “Come, ma fille.”

He took Léonie home in his light town chaise, and during the short drive she forced herself to talk gaily of the rout they had left, of this man and that, and a thousand other trivialities. Arrived at the Hôtel Avon she went at once to the library. His Grace followed.

“Well, ma mie, what now?”

“Now it is just as it used to be,” Léonie said wistfully, and sat down on a low stool beside the Duke’s chair.

His Grace poured out a glass of wine, and looked down at Léonie with a questioning lift to his brows.

Léonie clasped her hands about her knees, and stared deep into the fire.

“Monseigneur, the Duc de Penthičvre was there tonight.”

“As I saw, infant.”

“You do not mind him, Monseigneur?”

“Not at all, infant. Why should I?”

“Well, Monseigneur, he is not—he is not well-born, is he?”

“On the contrary, child, his father was a royal bastard, and his mother a de Noailles.”

“That was what I meant,” said Léonie. “It does not matter that his father was a bastard prince?”

“Ma fille, since the Comte de Toulouse’s father was the King, it does not matter at all.”

“It would matter if his father were not the King, would it not? I think it is very strange.”

“It is the way of the world, infant. We forgive the peccadilloes of a king, but we look askance on those of a commoner.”

“Even you, Monseigneur. And—and you do not love those who are base-born.”

“I do not, infant. I deplore the modern tendency to flaunt an indiscretion before the eyes of Society.”

Léonie nodded.

“Yes, Monseigneur.” She was silent for a moment. “M. de Saint-Vire was also there to-night.”

“I trust he did not seek to abduct you again?” His Grace spoke flippantly.

“No, Monseigneur. Why did he try to do it before?”

“Doubtless because of your beaux yeux, infant.”

“Bah, that is foolish! What was his real reason, Monseigneur?”

“My child, you make a great mistake in thinking me omniscient. You confuse me with Hugh Davenant.”

Léonie blinked.

“Does that mean that you do not know, Monseigneur?”

“Something of the sort, ma fille.”

She raised her head, and looked at him straightly.

“Do you suppose, Monseigneur, that he did it because he does not like you?”

“Quite possibly, infant. His motives need not worry us. May I now be permitted to ask you a question?”

“Yes, Monseigneur?”

“There was at the rout to-night a lady of the name of Verchoureux. Did you have speech with her?”

Léonie was gazing into the fire again.

“Verchoureux?” she said musingly. “I do not think . . .”

“It’s very well,” said his Grace.

Then Hugh Davenant came into the room, and his Grace, looking at him, did not see the tell-tale blush that crept to Léonie’s cheeks.

CHAPTER XXVIII

The Comte de Saint-Vire Discovers an Ace in his Hand

The comment that Léonie was exciting in the Polite World reduced Madame de Saint-Vire to a state of nervous dread. Her mind was in a tumult; she watered her pillow nightly with useless, bitter tears and was smitten alike with fear, and devastating remorse. She tried to hide these sensations from her husband, of whom she was afraid, but she could hardly bring herself to speak to her pseudo-son. Before her eyes, day and night, was Léonie’s image, and her poor cowed spirit longed for this daughter, and her arms ached to hold her. Saint-Vire spoke roughly when he saw her red eyes, and wan looks.

“Have done with these lamentations, Marie! You’ve not seen the girl since she was a day old, so you can have no affection for her.”

“She is mine!” Madame said with trembling lips. “My own daughter! You do not understand, Henri. You cannot understand.”

“How should I understand your foolish megrims? You’ll undo me with your sighing and your weeping! Have you thought what discovery would mean?”

She wrung her hands, and her weak eyes filled again with tears.

“Oh Henri, I know, I know! It’s ruin! I—I would not betray you, but I cannot forget my sin. If you would but let me confess to Father Dupré!”

Saint-Vire clicked his tongue impatiently.

“You must be mad!” he said. “I forbid it! You understand?”

Out came Madame’s handkerchief.

“You are so hard!” she wept. “Do you know that they are saying she is—she is—your base-born child? My little, little daughter.”

“Of course I know it! It’s a loophole for escape, but I do not yet see how I can turn it to account. I tell you, Marie, this is not the time for repentance, but for action! Do you want to see our ruin? Do you know how complete it would be?”

She shrank from him.

“Yes, Henri, yes! I—I know, and I am afraid! I scarce dare show my face abroad. Every night I dream that it is all discovered. I shall go mad, I think.”

“Calm yourself, madame. It may be that Avon plays this waiting game to fret my nerves so that I confess. If he had proof he would surely have struck before.” Saint-Vire bit his finger-nail, scowling.

“That man! That horrible, cruel man!” Madame shuddered. “He has the means to crush you, and I know that he will do it!”

“If he has no proof he cannot. It’s possible that Bonnard confessed, or that his wife did. They must both be dead, for I’ll swear Bonnard would not have dared let the girl out of his keeping! Bon Dieu, why did I not inquire whither they went when they left Champagne?”

“You thought—you thought it would be better not to know,” Madame faltered. “But where did that man find my little one? How could he know——?”

“He is the devil himself. I believe there is naught he does not know. But if I can only get the girl out of his hands he can do nothing. I am convinced he has no proof.”

Madame began to pace the room, twisting her hands together.

“I cannot bear to think of her in his power!” she exclaimed. “Who knows what he will do to her? She’s so young, and so beautiful——”

“She’s fond enough of Avon,” Saint-Vire said, and laughed shortly. “And she’s well able to care for herself, little vixen!”

Madame stood still, hope dawning in her face.

“Henri, if Avon has no proof how can he know that Léonie is my child? Does he not perhaps think that she is—what they are saying? Is that not possible?”

“It is possible,” Saint-Vire admitted. “And yet, from things he has said to me, I feel sure that he has guessed.”

“And Armand!” she cried. “Will he not guess? Oh mon Dieu, mon Dieu, what can we do? Was it worth it, Henri? Oh, was it worth it, just to spite Armand?”

“I don’t regret it!” snapped Saint-Vire. “What I have done I have done, and since I cannot now undo it I’ll not waste my time wondering if it was worth it! You’ll be good enough to show your face abroad, madame. I do not desire to give Avon more cause for suspicion.”

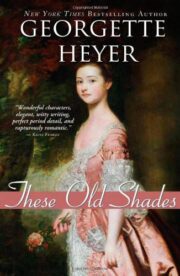

"These Old Shades" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "These Old Shades". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "These Old Shades" друзьям в соцсетях.