“Oh, Justin!” She clasped her hands, anger forgotten. “You think it enchanting still? I vow, I thought I looked a positive fright when I looked in the mirror this morning! ’Tis age, I suppose. Oh, I am forgetting to be angry with you! Indeed, I am so thankful to see you again I cannot be cross! But you must explain, Justin.”

“I will start mine explanation, Fanny, with an announcement. I am not in love with Léonie. If you will believe that it will make matters more simple.” He tossed the fan on the couch, and drew out his snuff-box.

“But—but if you are not in love with her, why—what—Justin, I don’t understand! You are most provoking!”

“Pray accept my most humble apologies. I have a reason for adopting the child.”

“Is she French? Where did she learn to speak English? I wish you would explain!”

“I am endeavouring to do so, my dear. Allow me to say that you give me very little opportunity.”

She pouted.

“Now you are cross. Well, start, Justin! The child is pretty enough, I grant you.”

“Thank you. I found her in Paris one evening, clad as a boy, and fleeing from her unpleasant—er—brother. It transpired that this brother and his inestimable wife had made the child masquerade as a boy ever since her twelfth year. She was thus of more use to them. They kept a low tavern, you see.”

Fanny cast up her eyes.

“A tavern-wench!” She shuddered, and raised her scented handkerchief to her nose.

“Precisely. In a fit of—let us say—quixotic madness, I bought Léonie or Léon, as she called herself, and took her home with me. She became my page. I assure you she created no little interest in polite circles. It pleased me to keep her a boy for a time. She imagined that I was in ignorance of her sex. I became a hero to her. Yes, is it not amusing?”

“It is horrid! Of course the girl hopes to intrigue you. La, Justin, how can you be such a fool?”

“My dear Fanny, when you know Léonie a little better you will not accuse her of having designs upon me. She is in very truth the infant I call her. A gay, impertinent, and trusting infant. I have a notion that she regards me in the light of a grandparent. To resume: as soon as we arrived at Dover I told her that I knew her secret. It may surprise you to hear, Fanny, that the task was damnably hard.”

“It does,” said Fanny, frankly.

“I was sure it would. However, I did it. She neither shrank from me nor tried to coquette. You can have no idea how refreshing I found it.”

“Oh, I make no doubt you found it so!” retorted Fanny.

“I am glad that we understand one another so well,” bowed his Grace. “For reasons of mine own I am adopting Léonie, and because I will have no breath of scandal concerning her I bring her to you.”

“You overwhelm me, Justin.”

“Oh, I trust not! I believe you told me some months ago that our cousin by marriage, the unspeakable Field, had died?”

“What has that to do with it?”

“It follows, my dear, that our respected cousin, his wife, whose name I forget, is free. I have a mind to make her Léonie’s chaperon.”

“Lud!”

“And as soon as may be I will send her and Léonie down to Avon. The infant must learn to be a girl again. Poor infant!”

“That is all very well, Justin, but you cannot expect me to house the girl! I vow ’tis preposterous! Think of Edward!”

“Pray hold me excused. I never think of Edward unless I can help it.”

“Justin, if you are minded to be disagreeable——”

“Not at all, my dear.” The smile faded from his lips. Fanny saw that his eyes were unwontedly stern. “We will be serious for once, Fanny. Your conviction that I had brought my mistress to your house——”

“Justin!”

“I am sure you will forgive my plain speaking. That conviction, I say, was pure folly. It has never been my custom to compromise others by my numerous affairs, and you should know that I am sufficiently strict where you are concerned.” There was peculiar meaning in his voice, and Fanny, who had once been famed for her indiscretions, dabbed at her eyes.

“How c-can you be s-so unkind! I do not think you are at all nice to-day!”

“But I trust I have made myself plain? You realize that the child I have brought you is but a child?—an innocent child?”

“I am sorry for her if she is!” said her ladyship spitefully.

“You need not be sorry. For once I mean no harm.”

“If you mean her no harm how can you think to adopt her?” Fanny tittered angrily. “What do you suppose the world will say?”

“It will be surprised, no doubt, but when it sees that my ward is presented by the Lady Fanny Marling its tongue will cease to wag.”

Fanny stared at him.

“I present her? You’re raving! Why should I?”

“Because, my dear, you have a kindness for me. You will do as I ask. Also, though you are thoughtless, and occasionally exceedingly tiresome, I never found you cruel. ’Twere cruelty to turn my infant away. She is a very lonely, frightened infant, you see.”

Fanny rose, twisting her handkerchief between her hands. She glanced undecidedly at her brother.

“A girl from the back streets of Paris, of low birth——”

“No, my dear. More I cannot say, but she is not born of the canaille. You have but to look at her to see that.”

“Well, a girl of whom I know naught—foisted on me! I declare ’tis monstrous! I could not possibly do it! What would Edward say?”

“I am confident that you could, if you would, cajole the worthy Edward.”

Fanny smiled.

“Yes, I could, but I do not want the girl.”

“She will not tease you, my dear. I wish you to keep her close, to dress her as befits my ward, and to be gentle with her. Is it so much to ask?”

“How do I know that she will not ogle Edward, this innocent maid?”

“She is too much the boy. Of course, if you are uncertain of Edward——”

She tossed her head.

“Indeed, ’tis no such thing! ’Tis merely that I’ve no wish to house a pert, red-headed girl.”

His Grace bent to pick up his fan.

“I crave your pardon, Fanny. I’ll take the child elsewhere.”

Fanny ran to him, penitent all at once.

“Indeed and you shall not! Oh, Justin, I am sorry to be so disobliging!”

“You’ll take her?”

“I—yes, I’ll take her. But I don’t believe all you say of her. I’ll wager my best necklet she’s not so artless as she would have you think.”

“You would lose, my dear.” His Grace moved to the door into the antechamber, and opened it. “Infant, come forth!”

Léonie came, her cloak over her arm. At sight of her boy’s raiment Fanny closed her eyes as though in acute pain.

Avon patted Léonie’s cheek.

“My sister has promised to care for you until I can take you myself,” he said. “Remember, you will do as she bids you.”

Léonie looked shyly across at Fanny, who stood with primly set lips and head held high. The big eyes noted the unyielding pose, and fluttered up to Avon’s face.

“Monseigneur—please do not—leave me!” It was a despairing whisper, and it amazed Fanny.

“I shall come to see you very soon, my babe. You are quite safe with Lady Fanny.”

“I don’t—want you to go away! Monseigneur, you—you do not understand!”

“Infant, I do understand. Have no fear; I shall come back again!” He turned to Fanny, and bowed over her hand. “I have to thank you, my dear. Pray convey my greetings to the excellent Edward. Léonie, how often have I forbidden you to clutch the skirts of my coat?”

“—I am sorry, Monseigneur.”

“You always say that. Be a good child, and strive to bear with your petticoats.” He held out his hand, and Léonie dropped on one knee to kiss it. Something sparkling fell on to those white fingers, but Léonie turned her head away, surreptitiously wiping her eyes.

“F-Farewell, Mon—monseigneur.”

“Farewell, my infant. Fanny, your devoted servant!” He made a profound leg, and went out, shutting the door behind him.

Left alone with the small but forbidding Lady Fanny, Léonie stood as though rooted to the ground, looking hopelessly towards the shut door, and twisting her hat in her hands.

“Mademoiselle,” said Fanny coldly, “if you will follow me I will show you your apartment. Have the goodness to wrap your cloak about you.”

“Yes, madame.” Léonie’s lip trembled. “I am—very sorry, madame,” she said brokenly. A tiny sob escaped her, valiantly suppressed, and suddenly the icy dignity fell from Fanny. She ran forward, her skirts rustling prodigiously, and put her arms about her visitor.

“Oh, my dear, I am a shrew!” she said. “Never fret, child! Indeed, I am ashamed of myself! There, there!” She led Léonie to the sofa, and made her sit down, petting and soothing until the choked sobs died away.

“You see, madame,” Léonie explained, rubbing her eyes with her handkerchief. “I felt so—very lonely. I did not mean to cry, but when—Monseigneur—went away—it was so very dreadful!”

“I wish I understood!” sighed Fanny. “Are you fond of my brother, child?”

“I would die for Monseigneur,” said Léonie simply. “I am here only because he wished it.”

“Oh, my goodness gracious me!” said Fanny. “Here’s a pretty coil! My dear, be warned by me, who knows him! Have naught to do with Avon: he was not called Satanas for no reason.”

“He is not a devil to me. And I do not care.”

Fanny cast up her eyes.

“Everything is upside down!” she complained. Then she jumped up. “Oh, you must come up to my chamber, child. ’Twill be so droll to clothe you! See!” She measured herself against Léonie. “We are very much of a height, my love. Perhaps you are a little taller. Not enough to signify.” She fluttered to where Léonie’s cloak had fallen, caught it up, and wrapped it about her charge. “For fear lest the servants should see and chatter,” she explained. “Now come with me.” She swept out, one arm about Léonie’s waist, and, meeting her butler on the stairs, nodded condescendingly to him. “Parker, I have my brother’s ward come unexpectedly to visit me. Be good enough to bid them prepare the guest-chamber. And send my tirewoman to me.” She turned to whisper in Léonie’s ear. “A most faithful, discreet creature, I give you my word.” She led the girl into her bedroom, and closed the door. “Now we shall see! Oh, ’twill be most entertaining, I dare swear!” She kissed Léonie again, and was wreathed in smiles. “To think I was so dull! ’Pon rep, I owe my darling Justin a debt of gratitude. I shall call you Léonie.”

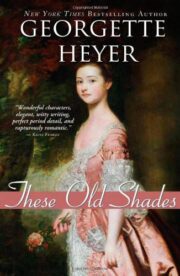

"These Old Shades" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "These Old Shades". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "These Old Shades" друзьям в соцсетях.