Sir Philip’s eyes flicked again to Henry. “Madam, I am familiar with the methods that General Tilney employs with his family. If you have been coerced — ”

“General Tilney is different from Henry. I have always been a little afraid of the general, but I could never be afraid of Henry. He has all my confidence, and all my affection.” The last sentence was said with such warmth of expression and such a smile that could leave no man in doubt that Catherine’s words were sincere.

Sir Philip looked at Henry and said, “You have a faithful little wife, Tilney, and I give you joy of her.”

Only then did Henry approach them. “I thank you, Beauclerk; I have great joy of her, I assure you.” He took Catherine’s hand and raised it to his lips.

“Forgive me, madam,” said Sir Philip. “I hope my misapprehension has not caused you undue distress.”

“Oh, no,” said Catherine, who in the flush of her success could not imagine ever feeling distressed again. “I am glad that we understand one another at last.”

“Yes; at last.” He bowed to her, nodded to Henry, and left the pump-room.

The Whitings joined them almost immediately. “Is everything well, Catherine?” Eleanor asked anxiously.

“Yes, I thank you. I forgot the speech I had planned, but I made Sir Philip understand me at last.”

“You were magnificent, my sweet,” said Henry. “Plain speech can do as well, and sometimes better, than the most learned oratory, or even one of Mrs. Radcliffe’s speeches.”

“It will be uncomfortable to be in company with Sir Philip, however. I wish I could have nothing more to do with him, but if General Tilney is determined on marrying Lady Beauclerk, I cannot see how we will be able to avoid him. I am sorry to say it, as they will soon be part of the family, but I do not like the Beauclerks.”

“We need have little to do with any of them beyond her ladyship,” said Henry.

“Will Miss Beauclerk go to live at Northanger Abbey when her mother is married, do you think?”

Eleanor exclaimed, and she exchanged a dismayed look with her brother.

“I had not thought of that,” said Henry.

“Surely my father would not — ” said Eleanor.

Catherine wondered at their words; why would it be so dreadful for Judith Beauclerk to live at Northanger Abbey with her mother?

“Perhaps Miss Beauclerk will marry Sir Philip,” said Lord Whiting. “He has lost his distraction — ” bowing in Catherine’s direction — “and may now remember what is expected of him and come up to scratch.”

“Oh, poor Mr. Shaw,” said Catherine.

Their attention was claimed at that moment by some acquaintances of the Whitings, and Catherine was left to her own thoughts. Though Mrs. Findlay’s accusations of murder had proved to be the workings of an imagination overly stimulated by horrid novels, that did not explain some of the other mysteries that surrounded the Beauclerk family. Mr. Shaw had spoken darkly of “services” he performed on his beloved’s behalf; could they have had anything to do with Sir Arthur Beauclerk’s death? Would Miss Beauclerk buy his silence with the money gained by a marriage to Sir Philip? And why were Eleanor and Henry so alarmed at the idea of Miss Beauclerk living at Northanger Abbey? Even without a murder in the case, there was no doubt that the Beauclerks were a very odd and mysterious family. Catherine had grown up a great deal since her adventures at Northanger Abbey, but there still was a part of her that longed to discover the truth of those mysteries; though in the social crush and swirl of a fine day of high season at the pump-room, murder and mystery seemed laughably improbable.

Chapter Twelve

Going to One Wedding Brings on Another

Friday night arrived as scheduled, and as Catherine’s pleasure in dancing had not been diminished by several exercises, the Tilneys went to the Lower Rooms for the weekly ball. The first set was forming as they arrived; Judith and Sir Philip Beauclerk stood at the top, ready to lead the dance. They took their places and the music began; too late, Catherine saw Eleanor waving to them.

“I should have liked to be next to Eleanor,” Catherine said to Henry.

“We will find them before the next,” he said, and then they were obliged to attend to the dance. Catherine watched Miss Beauclerk carefully so that she would be able to copy her figures, and was a little surprised to see that she was behaving towards her cousin — well, there was no other word for it but flirtatiously; and even more surprisingly, Sir Philip’s behavior was not much different. Henry also was watching the Beauclerks, his brow creased.

When the lead couple reached the Tilneys, Miss Beauclerk reached out and took Catherine’s hand, squeezing it quickly as she crossed over. She said, “Mrs. Tilney, I am so glad to see you!” and went around Henry with her usual light-footed grace. She crossed back and said, “I believe you have not heard my good news. You must wish me joy, for I am to be married.”

Catherine, startled, said, “To whom?” Had Mr. Shaw been able to convince Judith to accept his offer? But that romantic hope was dashed immediately.

“Why, to my dear Philip, of course!”

Catherine looked at Sir Philip, her eyes wide and her mouth open in surprise. How could he — it had not been a week since Sir Philip had acted towards herself as — oh! How could it be?

Sir Philip smirked at her confusion and gave her a little bow. “I thank you for the kind wishes you no doubt wish to bestow, Mrs. Tilney; the demands of the dance, I know, make it difficult.”

“I give you joy, Beauclerk,” said Henry. Only Catherine and Lady Whiting would have recognized the ironic edge of his words.

Certainly Sir Philip did not. “Dashed civil of you, Tilney,” he said, and they were gone, dancing with the next couple in the set.

“How could she do such a thing?” Catherine asked Henry. “She does not know about — ” She stopped, unable to discuss Sir Philip’s behavior in so public a place.

Henry, however, showed perfect comprehension. “Do not fret, my sweet. I suspect she knows more than you think.”

Catherine found such a thing hard to believe. How could Miss Beauclerk take a husband who did not scruple to seduce a married woman?

The Tilneys reached the top of the set and began to dance down; when they reached the Whitings, Eleanor gave Catherine a rueful smile. “I am sure that Judith Beauclerk was full of her news,” she said to Catherine. “Had I the opportunity to speak with you before the dance, I would have given you due warning, so you could meet Sir Philip with composure.”

“Thank you, but I do not think it would have made any difference,” said Catherine.

“One of our problems is solved, at least,” Henry said to his sister. “Judith will not be living at Northanger after a certain happy event. We should be grateful that she has so obligingly disposed of herself.”

“And given her mother an incentive to hasten that happy event,” said Eleanor.

They were then obliged to separate, and when they met again for the next dance, they spoke of more pleasant topics, but Miss Beauclerk and her cousin were never far from Catherine’s mind. It was all so unaccountable! She determined to give Miss Beauclerk a hint, a warning of some kind, but did not encounter her again until they were coming out of the tea room. She felt someone take her elbow and steer her away from Henry.

It was Miss Beauclerk, who whispered in her ear, “I wanted so much to speak with you before the dancing began. One can hear nothing over the musicians. Let us chat now before they start again. What do you think of my news? Is it not a surprise?”

“I am sure I wish you every happiness,” said Catherine.

“I thank you, Mrs. Tilney; that is most kind of you. It is all so exciting! Word got round so fast — as soon as we came in tonight, Mr. King engaged us to open the dance. By the bye, I think Philip would like to dance with you.”

“Please convey my thanks to Sir Philip, but I am engaged for the rest of the evening.”

“You have only been dancing with Henry,” said Miss Beauclerk, laughing. “I have no hope at keeping my husband so much at my side, I fear.”

Here was the opening Catherine had been waiting for. “Miss Beauclerk, have you thought about this very seriously? Are you sure that Sir Philip will make you a good husband?”

“Why should he not?” said Miss Beauclerk with a smile.

Catherine turned to face her, took her hands and leaned close so that no one could overhear; she had forgotten how much taller she was than Miss Beauclerk. She whispered, “I hope I am not saying anything wrong, but I must speak. Sir Philip — that is — he — ” Words failed Catherine, and she blushed deeply.

Miss Beauclerk looked at her with a knowing smile. “Oh, Mrs. Tilney, you are adorable! You mean to warn me about my rakehell cousin! I dare say he has been amusing himself by flirting with you, is that it?”

“I believe he intended more than a flirtation, ma’am.”

Miss Beauclerk smiled, her head tilted to one side, as if Catherine were some exotic foreign animal that she was observing at a zoo. “I do not understand; what has that got to do with me?”

“Are you not afraid he will continue to — flirt — with other women after you are married?”

Miss Beauclerk shook her head and laughed. “You are a dear thing! But you need not worry about me, Mrs. Tilney. I am no romantic young miss. I shall take good care that my husband does not tire of me; and if he does, I shall accept it with good grace. And who knows, perhaps I shall have flirtations of my own!”

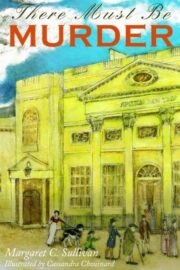

"There Must Be Murder" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "There Must Be Murder". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "There Must Be Murder" друзьям в соцсетях.