“Indeed.” Henry reached for her hand and kissed it. “Emily and Valancourt await us, my sweet. Shall we retire?”

“I am ready.” Catherine neatly folded her sewing.

“I beg your pardon, MacGuffin,” Henry addressed the Newfoundland curled up at the foot of his chair. “It is time for bed, lad. I cannot rise while you are sleeping on my feet.”

MacGuffin raised his shaggy head and gazed up at his master adoringly, his tail thumping the floor. A string of saliva glistened at the corner of the dog’s mouth, trailing down to the old blanket placed on the floor expressly to absorb the excess. Henry gently lifted his foot in an encouraging nudge, and the dog uttered a weary moan and heaved his massive bulk to a standing position.

“Shall you let the dogs out?” Catherine asked her husband. The house terriers, lying in a tangled heap by the fire, looked round at her utterance of that favored word, “out.”

“Matthew will attend to that.”

As they passed out of the drawing room, followed by the clicking of canine claws on the wooden floor, a figure loomed from the shadows of the passage. Catherine started and gave a strangled cry.

“Beg pardon, Mrs. Tilney,” said Matthew. Matthew was the rector’s groom, clerk, and factotum; an accomplished huntsman, he glided about the parsonage as silently as he moved through the woods, frequently (and quite inadvertently) startling his mistress. However, Catherine liked Matthew, and it was not in her nature to bear a grudge, so she smiled her forgiveness.

Matthew snapped his fingers at the dogs, and they followed him down the passage toward the rear of the house as the Tilneys climbed the stairs to their bedchamber.

Henry had a genius for piling the pillows so that he could sit up in bed and read comfortably, even with one arm round Catherine’s waist and her head resting upon his shoulder. The fire burned brightly, and the Tilneys curled up warmly together under the quilts as Henry read aloud from Mrs. Radcliffe’s novel, The Mysteries of Udolpho.

“Valancourt,” Henry read, “between these emotions of love and pity, lost the power, and almost the wish, of repressing his agitation; and, in the intervals of convulsive sobs, he, at one moment, kissed away her tears — ”

Henry stopped reading and scattered several quick kisses across Catherine’s face. She giggled and prodded him in the chest. “There are no tears here, sir. Pray continue.”

“I would much rather kiss you.”

“Read!”

“I hear and obey, madam.” Henry returned to Udolpho. “Now, where was I? Oh, yes — kissed away her tears, then told her cruelly, that possibly she might never again weep for him, and then tried to speak more calmly, but only exclaimed, ‘O Emily — my heart will break! — I cannot — cannot leave you! Now — I gaze upon that countenance, now I hold you in my arms! A little while, and all this will appear a dream. I shall look, and cannot see you; shall try to recollect your features — and the impression will be fled from my imagination; — to hear the tones of your voice, and even memory will be silent! — I cannot, cannot leave you!’”

The first time Catherine read Udolpho, she had wept over this passage; but when Henry read Valancourt’s dialogue, he used such a simpering, affected voice that she found herself laughing at the poor Chevalier’s distress.

“‘Why should we confide the happiness of our whole lives to the will of people, who have no right to interrupt, and, except in giving you to me, have no power to promote it? O Emily! Venture to trust your own heart, venture to be mine for ever!’ His voice trembled, and he was silent; Emily continued to weep, and was silent also, when Valancourt proceeded to propose an immediate marriage, and that, at an early hour on the following morning, she should quit Madame Montoni’s house, and be conducted by him to the church of the Augustines, where a friar should await to unite them.”

Henry stopped reading and pondered for a moment. “The banns were not published? No license obtained? A curious business; I dare say that the brave Valancourt might have found the Augustine friar less receptive to his scheme than he anticipated.”

“It is only a story, Henry,” said Catherine in the patient tone used to educate the slow-witted.

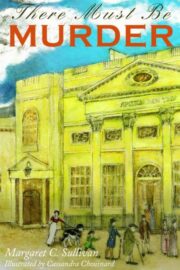

"There Must Be Murder" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "There Must Be Murder". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "There Must Be Murder" друзьям в соцсетях.