“Your Majesty,” Howard said.

The tension in the silent chamber cracked; still no one moved.

“What say you?” Elizabeth interposed calmly.

“The Queen, Your Majesty—the Queen is dead.”

Elizabeth went slowly to her chair, seated herself, patted her skirts into place and linked her hands calmly in her lap.

“I am sorry that you bring such news,” she observed.

Her elderly relative looked somewhat taken aback at this impassive reception. He went on, with the air of someone whose effect has somehow missed fire, but who is carrying on notwithstanding.

“We have come, therefore, to fetch Your Gracious Majesty to London—when it please you to come there—to take the throne.”

“It cannot please me,” Elizabeth pronounced.

Howard turned to exchange an incredulous look with his gentlemen. Elizabeth proceeded.

“I am too overcome at the death of my sister. I could not travel now, with such grief.” She faced the speaker levelly: “Go back to Court, my lord, and tell that to the Queen. …”

Howard’s face went slack and blank. Once again he and the men behind him exchanged helpless looks. On the opposite side of the room, Dudley, Carew and Ashley stood quite still, Dudley with his arms crossed, Ashley with her eyes fixed on the floor.

Howard tried again.

“Most gracious Queen Elizabeth—I think—you did not hear me.”

“My ears are excellent,” Elizabeth informed him briskly, “and you speak your words well. Tell the Queen for me I am prostrate at her death and cannot leave Hatfield. …”

Howard was a grotesque and even pitiable sight: the Lord Chamberlain completely flummoxed… He rose awkwardly, backed a step or two, and one of his gentlemen stepped forward with a loud preliminary clearing of his throat. Before he could speak, Parry charged into the room. His face was red and transfigured.

“Bess—Bess—there be—”

He stopped abruptly.

“Your—Majesty—there is another come from London, ridden in haste… , He—”

“Speak up, Thomas,” Elizabeth bade him with a cheerful indifference. “What is it?”

“He—” Parry looked behind him, gave a final wheeze of relief. “Thank God, here he is himself! Let him speak it.” William Cecil, moved out of his muted imperturbability, moved by incredible agitation and haste, was there. At sight of him, astonishment and unspeakable realization broke across the faces of Dudley and Carew; and Ashley whispered, “Oh God!” below her breath and began to weep joyfully, .j. . “Cecil!” Elizabeth breathed.

He dropped to his knees, extended his hand beneath her eyes.

“Your Majesty, I came to bring you—this.”

Elizabeth gazed down at the glistening object on his palm. And not till afterward did either she or Cecil remember that his hand shook till the jewel flashed and glowed… Slowly, she picked it up, turned it in her fingers, still gazing.

“Never leave her finger till she was dead …” Elizabeth said slowly. And then, as though to her own soul and none other: “This is God’s doing. And marvelous to mine eyes.” She stood up slowly, with her own peculiar grace, erect as a sapling, though she was trembling from head to foot. She slid the great ring onto her finger and clasped her hands together. The dazed look went from her face; she smiled at the circle about her.

“My lords, you have ridden hard and far, and must be tired indeed. Dear Ashley, take them below, and give them to eat and drink. We will speak of these things together, when they have rested.”

Ashley’s sedate head in its gray veil was suddenly inches higher. She trod to the door with immense dignity and nodded to Lord William and his companions with a bland smile.

“My lords,” said Ashley, much as though she were ushering a troop of children downstairs to a feast…

They bowed to the ground to Elizabeth, and bowed to the ample figure of Ashley, sailing ahead of them, swelling with happiness and importance.

“Peter, go with them. Thomas, see to what company they have brought.”

“I will, Your Majesty… Your Gracious Majesty,” Parry quavered, and lumbered out of the room.

Dudley and Cecil stood waiting, their eyes on the slender figure and luminous, taper-pale face.

“Stand here beside me, both of you,” Elizabeth said suddenly. “It is not true! …”

Dudley took her hand where the heavy ring shone and lifted it to the level of her eyes, smiling as he did so. Her hand closed on his.

“Robert, you said we should ride the free roads of England. Do you remember?”

Dudley bent his head.

“Get me a white horse, Robert, pure white—the best in England. And for yourself a black, for you shall ride behind me… And let word go forth, and all the people come to see me as I would see them, each last and little man.”

She turned quickly to Cecil.

“Cecil, what is our inheritance?”

“Little enough, madam,” he answered.

“I know—I know—” Elizabeth said, but there were life and light vibrating in her voice.

“A halting army,” Cecil said. “Few ships, no treasury, and bread too dear the loaf to be bought by most. ’Tis a poor realm and a sick one.”

A strange smile came into her face. She let her breath out in a long sigh.

“Aye! But by God’s hand it is mine. And so it shall be my care, as long as I—”

“Your Majesty,” the two voices said as one voice. Dudley and Cecil went to their knees.

Over their bent heads Elizabeth’s tranced eyes fixed, looking far beyond them.

“—As—long — as—we—do—live” said the Queen.

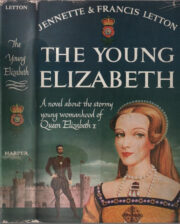

Jennette and Francis Letton, authors of THE YOUNG ELIZABETH

"The Young Elizabeth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Young Elizabeth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Young Elizabeth" друзьям в соцсетях.