“What! Full? And going from his chamber. How’s this? You were sent for? When?”

“Ten minutes ago, sir. And I hurried,” the lad stammered, his eyes like a scared rabbit’s. “I hurried, indeed, sir … but they would not receive me. They would not let me pass. …”

Seymour smiled, his frank, teasing smile that went across his ruddy face like sunlight glancing.

“Would not receive you, eh? Well, get you to the kitchen. Hold—” as the page scurried away. “As you pass the Queen’s chambers, lad, speak quietly—quietly, mind—to one of her women. Say she is wanted here.”

“Aye, my lord.”

Tom Seymour turned then, and went on up the stairs, the smile still playing about his lips—but his eyes steady, clear, and purposeful. In this teeming world of the court, there might be smiling in plenty, but few persons smiled with the open frankness of sunrise, like Tom Seymour. This man towered above the miasma of dread and uncertainty as he towered above other men in stature. The whispers, the lies, the tortuous policies he shook from him like a cloud of midges. He did not know the meaning of fear; nor, even now, in middle age, the meaning of diplomacy. He was filled with an unassailable self-confidence, and with supreme optimism. What he thought and felt were shouted out for any wind to carry. It was all part of the unquenchable boyishness which was his charm. But it was a trait which made his eldest brother, Lord Edward Seymour, shake his narrow head, and tighten his thin lips.

Tom went now deliberately up those stairs, toward that door behind which history was moving to the end of an era.

“Guard!” his voice rang out, unafraid.

“My Lord?”

“Come down to me, man.”

Seymour halted on a stair, stood in an easy nonchalant pose, hand on hip. The man hesitated, obviously at a loss.

“Oh come!” Tom laughed. “Lower your halberd. I'll not break entry! Do you know me?”

“My Lord Seymour!” the man muttered, on a sheepish gulp of protest, and cleared his throat.

“So! That’s better. Now, tell me: is my brother within?”

The guard came down slowly, and stood on the steps above him.

“Well?” Seymour said rallyingly. “Speak, fellow? Answer me? You’re afraid to speak? The door’s thick enough… Though even were you on the other side of it, I’ll warrant His Majesty couldn’t hear you—”

The man stiffened, looked about him with that apprehensive unease which Seymour knew only too well. He’d seen it in a thousand faces; and that quick turn of the head, on the alert for an unseen listener, he knew that too.

“Come—fear not!” he said roundly. “Kings go. And others come to take their places. But there are those who come with kings to whom respect is politic… Now, answer me: who’s with him?”

The man swallowed, and straightened his shoulders.

“Bishop Gardiner, my lord.”

“Ah … and who else?”

“William Cecil.”

“Who besides? My brother?”

“Aye, sir. Lord Hertford is within.”

“Enough!” Seymour said peremptorily.

Quickly and with evident relief, the guard went back to his station at the door and took up his position once more. Seymour turned and walked down the stairs, and he was not smiling now. His jaw was thrust forward under the rich, curling beard. He ran his fingers through his thick hair. So … there was a worm attacking the coffin even before it was closed and sealed… Well, he’d expected as much.

Suddenly, down the passage, came darting a lean figure with a pinched, tight face. His doublet and cloak of velvet only served to emphasize the rodent sharpness of his features and the bony gracelessness of his spare frame. God’s soul! Tom thought, he looks the ferret that he is…

Sir Robert Tyrwhitt had almost brushed past him, then paused, with a start of recognition.

“Lord Thomas … I did not look to find you here. Where is your brother?”

“Can you not smell him out, Robert Tyrwhitt?”

Tyrwhitt drew himself up. The movement added nothing of dignity to him, and Seymour’s lips twitched with contemptuous amusement.

“I’ve things to do, matters to look to, of more importance than to loiter here and cross words with you,” he retorted. There was venom in his tone and in his exasperated eyes.

“Then go your ways and set about them,” Seymour advised him. “Hunt out your rats and rabbits under some other hedge… What if my brother should find you here?” “He knows I’m loyal to him!” Tyrwhitt spoke quickly. Tom Seymour threw back his fine head and laughed. Tyrwhitt frowned sharply, threw a glance at the door.

“You little ferret!” Seymour said derisively. “Your nose is pinched up. You’ve lost your scent. Why don’t you pick yourself a man for this vast loyalty of yours? Pity it should go to waste and for no purpose—”

“A man? Who? Yourself?” Tyrwhitt sneered.

“I, too, am uncle to the Prince,” Seymour reminded him with a certain level emphasis that was a sudden change from his flippant jeering of the moment before. “And the boy loves me well,” he added. “Had you chanced to remember that? It is well enough known.”

Tyrwhitt moved nearer to him.

“I did not mean to seem unfriendly, my Lord Seymour,” he offered placatingly. And then, in a burst of peevish apology, “You have a trick of talk to rile any man alive!” Seymour took him by the sleeve in easy fashion, but still without smiling.

“Nay, I would not wish to rile you. Maybe Fm somewhat jealous that you’ve been sent for by my brother, and not I.”

“My lord, I was not sent for!” Tyrwhitt protested eagerly. He lowered his voice to a confidential murmur. “But the Queen was… He laid a slight stress on the third word.

“No!” Seymour exclaimed.

“Aye!” Tyrwhitt asserted nodding his head.

Seymour, still holding his arm, steered him a pace or two down the passage, sauntering beside him.

“I thank you for this news,” he observed with a bland sarcasm that was lost on the other man. “If the Queen’s Grace has been summoned, and so comes, would you dare have her find you here? In times like this a man’s act may be construed to do him ill… Get you to the kitchens, Robert. If there is aught to be known, they’ll know it there. Go; get you below stairs, man, and find the heart of the matter.”

“Aye, my lord,” Tyrwhitt said dubiously and without relish. But curiosity won. He hurried away.

Thomas Seymour stood waiting. Within a few moments the soft rustle of sweeping skirts came to his ears, the sound which eddied perpetually through the palace like the ripples of a low tide whispering over the sand.

Unannounced, unattended, Queen Katherine Parr came. And if any seal needed to be set upon the crucial importance of this hour it might be seen in that…

Katherine Parr was not a regal figure; she was a comely, merry woman with bright hair. You could see her more readily as cheerful mistress of a country manor than as Queen of England. She was infinitely kind, warmhearted and gracious, with the winning grace of simplicity. And she possessed that particular quality of imperturbability which is the blessing of those uncursed by too much imagination. It had stood her in good stead as wife and tender nurse to the wreckage that remained of what had been King Henry.

She started at the sight of Thomas Seymour and halted, her great skirts of purple velvet falling heavily about her. A rush of bright color came into her pale face, strained with apprehension and drawn from want of sleep, a girl’s warm color. Katherine was in her early thirties, but in this moment of sudden and unlooked — for encounter her face broke into that look of youth which Tom Seymour’s would never lose as long as he lived.

The King had been her third husband. Her family had married her off to an elderly widower, when she had been scarcely fifteen. Then it seemed that the homemaking, merry qualities of this lovable girl were fatally marketable from a family’s point of view…

Even her own stepchildren loved her… Widowed for the second time, she had loved for the first time: and the man to whom her warm and honest heart was utterly given was the handsome Tom Seymour. But before the marriage she longed for could take place, a third man saw her for the comforting household goddess that she was. Harry, the King, another father of motherless children, took her in marriage…

Now, at the foot of the stairs leading to the King’s deathbed, here she was face to face with the man she loved above all others.

“Thomas!” It was not so much a whispered word as a caught breath.

“You were sent for,” Thomas Seymour stated rather than asked.

“Aye,” Katherine answered with a shiver. And swept to the stairs.

He stood before her, his tall figure barring the way.

“You were, indeed. By me.”

“Thomas! This is no time for play-acting. He’s dying — let me pass.”

“I sent for you, Kate.”

Katherine struck her ringed hands together in a gesture of panic. The ruby cross at her round white throat glowed and sank like blown embers with her quickened breathing.

“Tom! Tom! Will you be more circumspect? One day you will speak out like this in front of others than those—” she indicated the two scarlet statues at the head of the stairs before the chamber door—“and then, what?”

“You used not to speak with me thus, Kate,” he said softly.

“What’s past is past… I’m the King’s wife.”

Seymour drew nearer, looked down steadily into her working face.

“I think not. I think you are—his widow.”

Katherine’s locked hands flew to her breast.

“Have they told you?” she breathed.

Seymour shrugged his broad shoulders.

“The vultures gather.”

Katherine uttered a small sound of disgust mingled with compassion.

“They’ve been gathered for weeks past, torturing an old man too ill and spent to battle with them.”

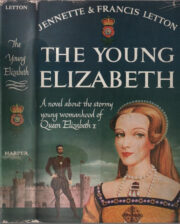

"The Young Elizabeth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Young Elizabeth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Young Elizabeth" друзьям в соцсетях.