It was while he was riding down the village street that he had met the two elder daughters of the Earl of Claymore. He had raised his hat, made his bow, and prepared to ride on. But Lady Melissa Wade had stopped with the obvious intention of conversing with him, while the other girl had bowed rather haughtily and passed into the milliner's shop behind her. Lady Melissa had asked him if he was to attend Lord Graham's ball the following evening. Her intention had been obvious. She must have known very well that he would be there.

Nevertheless, Mainwaring had fallen into the trap almost willingly. If he must forget the past, and if he must resist the temptation presented by the little wench, then what better way was there to do both than to attach himself to another lady? He must only be careful not to so single her out as to feel himself honor-bound to offer for her.

"May I hope that you will reserve the first set for me, Lady Melissa?" he had asked, smiling down at her. "Or am I too late and your card is filled already?"

She had tittered. "Really, sir," she had said, "you are not in London now. We do not generally choose partners before the ball begins, you know. But I should be delighted to reserve the set for you. What a delightful horse you have, Mr. Mainwaring. He is very obedient despite his great size and strength."

"We have been a long way together," he had said, patting his horse's flank.

"Indeed?" she had said. "I was under the impression, sir, that you did not have much love of horses. Riding is one of my greatest pleasures. I insist on exercising my horse myself each morning, no matter what the weather."

"Perhaps we could ride together one morning," he had suggested politely.

"Oh," she had said, raising surprised eyes to his, "what a perfectly splendid idea. I would have to ask Papa if I may, of course. But I think he will agree, provided I take a groom with me."

"Until tomorrow evening, then," he had said, raising his hat and bowing to her again before riding off to the vicar's house with the grim satisfaction of having done the right thing to try to set his life in order.

That had been the day before. But somehow matters did not appear so simple in the light of morning. It was a particularly beautiful day. He had no commitments until the evening. And when he went into his library to select a book to read on the terrace outside, he took down, without conscious choice, his, copy of Lyrical Ballads. The volume opened on its own to a much-loved poem-one about Lucy. And he smiled as he read about her:

She dwelt among the untrodden ways

Beside the springs of Dove,

A Maid whom there were none to praise

And very few to love:

A violet by a mossy stone

Half hidden from the eye!

– Fair as a star, when only one

Is shining in the sky.

William Mainwaring looked up and smiled. The poet might almost have been describing his wood nymph. Nell. And she would be waiting for him that afternoon perhaps, wondering if he would keep his promise to read her some of these poems. There was something of a poet in her, something of an artist, he felt sure. If only she could have had the benefit of an education, she probably would have been a very interesting person. Not that there was anything dull about her now. She would enjoy hearing these poems, he was convinced. Should he go and read them to her?

Could he go and keep himself from touching her? Just yesterday at this time perhaps he could have answered in the affirmative with some confidence. But he had touched her already, and that brief embrace had awoken a hunger in him that he did not believe he could easily quell. It would be far safer to stay away. Far safer for her and far better for his self-respect. He did not like himself for hungering after one woman while loving another.

Perhaps the very best thing he could do with his life would be to marry Lady Melissa Wade. He did not think he was flattering himself to believe that she would accept him. She was a pretty girl with her fair hair and blue eyes, and she seemed amiable enough. He could never love her, or feel any deep affection for her in all probability, but then, chances were that she would not expect any such devotion. With her his life would take on some stability. With her he would be able to satisfy those physical cravings that the girl in the woods had just reawakened. And with her he would be beyond temptation. He did not believe that his conscience would allow him ever to stray to another woman if he had a wife to whom he owed his loyalty.

He got up from his seat on the terrace and wandered back to the library. But he did not put the book back on the shelf. He tapped it against his free hand and stared sightlessly at the titles before him. If it was to be so, if he really was to take such an irrevocable step, perhaps it would be safe to see Nell one more time. After all, he had almost promised her that he would go. He would see her that afternoon and begin his serious courtship of Lady Melissa that evening at Lord Graham's ball. It was very possible that the girl would not be there, anyway, and then matters would be taken out of his hands.

William Mainwaring strode out of the library and took the stairs up to his room two at a time, the volume of poems still clasped in one hand.

Despite the precaution she had taken of hiding her shabby cotton dress close to the western edge of the wood and putting it on before going to the clearing by the stream, Helen was again the first to arrive there. Indeed she thought he was not coming. Time seems long when one is waiting for someone one is not even certain will come, especially when one dare not fill in the time with a book or a sketchpad. She was sitting a little back from the stream, sheltering from the heat of the sun beneath the shade of a large tree, when he came. She sat cross-legged, her chin resting on one fist. She did not move when she saw him come.

"Hello, wood nymph," he said, stopping when he was still several yards away from her and smiling.

It was the smile that did it. She knew beyond any doubt that the unthinkable had happened. She loved him. She could not believe ill of his motives. There was such gentleness in his smile. "Hello," she said.

"You see?" he said, holding up the volume he clasped in one hand. "I have brought the book. You will like some of the poems, I believe." He came and sat beside her under the tree so that she felt suffocated, unable to breathe freely. "You do not look very pleased," he added. "Am I forcing myself and my interests on you, Nell?"

"Oh, no," she said, and looked up into his dark eyes, I disturbingly close to her own. "I thought you were not coming, and I would have been disappointed if you had not. Please read to me."

"Would you?" he asked. "Have been disappointed, I mean? I would have been here sooner, but I had an unexpected visitor and had to stay and be civil."

He looked across at her as if he expected her to say something, but she looked back silently. Finally he opened the book and thumbed through the pages. She waited with great interest to see which poem he would choose to read first.

"Here it is," he said at last. "This, I think, you will appreciate. It is one of my favorites."

And he began to read her the poem about the rainbow, which was not one of her favorites-it was her very favorite.

My heart leaps up when I behold

A rainbow in the sky;

So was it when my life began;

So is it now I am a man;

So be it when I shall grow old,

Or let me diet

The Child is father of the Man;

And I could wish my days to be

Bound each to each by natural piety.

He read slowly and distinctly, savoring every word.' By the time he had finished, Helen had her eyes tightly closed, enthralled as much by his voice as by the sentiment of the poem.

"Do you like it?" he asked.

"Oh, yes." Her eyes flew open and looked into his. "It is just exactly as I feel, you see. But people keep telling me that I shall grow up one of these days and that I shall then become interested in the more important things of life. I shall not. I would rather die!"

He smiled gently and his eyes dropped involuntarily to her mouth. "You need not fear, little wood nymph," he said. "You will never change. At least, you will never lose your love for what you have now. It is too deeply a part of your nature, I think."

She could feel tears welling to her eyes and dropped them hastily to look at the grass between them. No one had ever understood before, and no one had ever spoken with approval of her strange tastes. Was it possible that he felt about her as she felt about him? But, no. He was to dance with Melissa that very evening, and ride with her one morning soon. He would perhaps be betrothed to her before the summer was out. And she herself was a mere village wench, as far as he knew. She jumped to her feet suddenly and moved away from him among the trees.

"What is it, Nell?" he called after her.

She did not answer. But she did not run far away, either. She merely wanted a few moments to collect herself. She did not want their afternoon to end so soon, their last afternoon. Within a few hours he would know who she was, and his approval would turn to amusement at the best, contempt at the worst. It was perhaps acceptable for a serving girl to love the woods and the sky and the stream, but there was something definitely odd about a society girl who preferred those things to. fashion and gossip and visits. She stopped at the big oak that she had climbed the day before and leaned against it, resting one cheek against the rough old bark and wrapping her arms as far around it as she could reach. She closed her eyes.

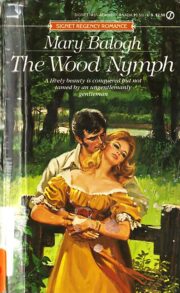

"The wood nymph" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The wood nymph". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The wood nymph" друзьям в соцсетях.