That activity was stopped abruptly when her mother appeared in the room and suggested very gently that such violent playing would only bring about a recurrence of her headache. Helen had no choice but to meekly agree.

Sunday came finally and it was necessary to go to church. Helen always looked forward to the outing. She was not at all interested in the bonnet parade, which seemed to be the chief interest of most of the female part of the congregation, or in the game of attracting more admiring male glances than any other young lady present. Helen loved the building and the ritual of the service.

The church was ridiculously large for such a small village. It was never more than one-third full, though everyone within a five-mile radius came on Sunday mornings, come rain or shine. But to Helen its very size was its attraction. It was a cold stone building, uncomfortably cool even in the height of summer. Its Gothic doorway and stained-glass windows, its high arched ceiling all reached toward heaven. She loved to see the vicar in his vestments. Dull, ordinary Vicar Brayley became in church a figure of great dignity, and his voice, hesitant and monotonous during conversation, took on power and authority when he read from the Bible or chanted a psalm.

On this particular Sunday she was not so eager to go. Mr. Mainwaring was bound to be there. He would see her, and her humiliation would be very public. Miraculously, though, he did not see her, not to recognize, anyway. She wore her bonnet that had lace piled on the crown and she pulled the lace down over her face when they went into the church. He was indeed there but sat at some distance from the earl's family. After the service was over, Helen made an undignified bolt for her father's carriage while the rest of the congregation stood around in groups for fully twenty minutes.

"I was afraid that the sunshine would bring back my headache," she explained feebly when the rest of her family joined her.

"And what on earth were you doing with the lace from your bonnet all down around your face?" Emily asked. "You did look a fright, Helen. You looked as if you were in deep mourning, except that the hat is blue and not black. I was quite mortified to be seen sitting in the same pew as you."

"Mr. Mainwaring must think you quite a freak," Melissa added. "You ran away like a frightened rabbit, Helen. You will have us all thinking that you are afraid to meet the man for some reason." She turned to her older sister. "Mr. Mainwaring has offered to take me driving this afternoon, Emmy."

Helen wished suddenly that she had walked home instead of waiting twenty minutes in a stifling carriage.

And so it was Monday afternoon before Helen finally managed to escape to the woods again'. She changed into her cotton dress, loosened her hair, kicked off her shoes, and pulled off her stockings. She wanted to read; she wanted to write; she wanted to paint. But she would do none of these things. If Mr. Mainwaring came, he would know immediately that she was no village wench if she had a book or a brush in her hand. And she wanted him to come. She had tried to tell herself all morning that she wished to come here merely so that she could be alone and free from the fetters of her life again. But she wanted to see him.

She paced the bank of the stream, dangled her feet in the water, twirled around the trunk of a tree, and finally climbed the branches of the old oak tree, which had been created for that purpose. She wedged herself high up, her back against the sturdy trunk, her knees drawn up, and her feet resting on a branch. She watched and watched for him. And finally she looked up and became absorbed in the pattern the branches and the leaves made against the sky, and in the changing face of the wide blue expanse above her as wisps of cloud scudded across it.

It had not been an easy week for William Mainwaring. He had read and reread the letter from Hetherington, feeling alternately comforted that they still wished to be his friends, and yet hurt to know that they were apparently happy together, that they were expecting a child. The child had probably been born already, in fact. In some ways it might have been better never to have known how their marriage was progressing. He had to feel happy for Elizabeth. After all, he loved her, and love could never be a wholly selfish emotion. And he had known even when he planned to marry her himself that she loved Robert. He was glad for her that her story had had a happy ending at last. But his own pain was not therefore lessened.

He loved her still. The longing only became stronger with time, in fact. He dreamed frequently of what it would be like now to live at Graystone with Elizabeth as his wife. With her perhaps he could enjoy the social life of the neighborhood, which he was finding something.of an ordeal. There were several families here that he could like if only he had her with him to please them with her warm charm and her never-failing ability to converse with even the dullest person.

He had finally written back two days after receiving the letter. It was a reply that accepted unconditionally the renewed offer of friendship and that accepted a full measure of blame for the unpleasantness that had happened in the past. He congratulated them on the expected birth. But the letter was noncommittal about their invitation. He could not yet contemplate the thought of seeing them, of knowing beyond a doubt that he was nothing more than a friend to the Marchioness of Hetherington.

Mainwaring made an effort to appear agreeable to his neighbors, most of whom had devised some entertainment for his benefit. He had even forced himself to invite Lady Melissa Wade to go driving with him after church on Sunday. It was true that he had been almost maneuvered into doing so when she had answered with alacrity the question he had put to her father about the best direction to take if one wanted to see some attractive countryside. But even so, he did not try to avoid the excursion. He must somehow force himself to live on, he supposed, and the girl at least was willing to do most of the talking with only the occasional prompting from him.

He had still not met the youngest of the earl's daughters. It seemed almost as if she were avoiding him, though he could not imagine why she would do so. A few of his new acquaintances, though, had hinted that the girl was "strange," something of an eccentric. If only she knew how little she had to fear from him.

Always through the week his thoughts came back to the little wood nymph. After a few days it was difficult even to believe that she had been real. How delightful it must be to belong to the lower classes, with nothing to worry about but the day's chores. The girl had seemed so free from care. He constantly felt himself resisting the urge to go back to the woods to see if she was there, and to see if his first impression would remain. Perhaps if he saw her again, she would appear merely dull or vulgar.

He did not wish to go. It would not do to become involved in any way with a girl of a different class. Mainwaring had always frowned heavily on those men – and there were many-who felt that women of a lower class were theirs for the taking, that virtue counted for nothing if the female were not a lady. He had never been able to bring himself to use even a dancer or a prostitute. He could see them too clearly as women, persons, who at some time had been down on their luck and forced to sell the only commodity that was wholly theirs. His little wood nymph should be left alone to enjoy whatever solitary pleasures she gained from her "special place," as she had called it.

Yet he found that by the Monday he could no longer stay away. He needed to be alone, he told himself. It was a beautiful day and a walk would do him good. She would probably not be there anyway. After all, it could not be easy for a girl to get away from home in the middle of the day. But it was a pretty place, her spot by the stream. He would go and see it again.

At first he thought that she was not there. There was no one today leaning over the stream studying the colors and movement of the water. He tried to convince himself that he was not at all disappointed. And then he saw her, perched high up in an oak tree, apparently perfectly relaxed, not clinging for safety by so much as a single hand. She was gazing upward, quite unaware of his presence.

William Mainwaring smiled with genuine amusement. He had to quell the desire to laugh outright.

"Hello, wood nymph," he called. "Are you learning sky today, or is it branches?"

She looked down. "You are mocking me," she said. "If you were up here, you would see that the clouds are moving fast across the sky, but it is not windy here. Is not that extraordinary? Do you imagine there is a gale blowing up there?"

"I can only be thankful that there is no gale down here," he said. "You would be blown out of the tree like a leaf in autumn."

"Nonsense," she replied. "I am perfectly safe. I have climbed this tree a thousand times or more."

"Wood nymph!" he said. His voice was almost a caress. "Would you please humor a poor earth-bound mortal and come down from there?"

He marveled at how surefooted she was as she descended quickly. She must be very used to walking in bare feet, he thought, if she did not hurt them against the bark of the tree. He held up his arms when she reached the lowest branch.

"Let me help you," he said.

"I have jumped it safely a thousand times," she replied, but she put her hands on his shoulders and allowed him to swing her to the ground.

She looked delightfully wild, he thought, with her large, rather dreamy gray eyes and tangled tawny hair and with her faded shabby dress that ended a full inch above her bare ankles. He reached out to take a leaf from her hair.

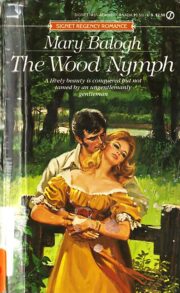

"The wood nymph" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The wood nymph". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The wood nymph" друзьям в соцсетях.