The shining eyes and the glowing cheeks that so pleased Elizabeth were due as much to this acceptance of the past as they were to the renewal of her determination to paint.

Although Helen sometimes forgot that she was a guest and that she should spend more time with her hostess, she did enjoy Elizabeth's company when they were together. She had been grateful to her for the invitation to Hetherington, but she had not really expected to like her hostess. Despite what Elizabeth had said to her about her own sufferings, Helen had labeled her as one of the privileged in this life, as one who had not really been made to face the harshness of life as most other people had.

She was pleasantly surprised, therefore, to find that Elizabeth had a warm personality and a keen intelligence. Her love for her husband and son were no affectation. She wrote to the marquess daily, though he was planning to come a week after their own arrival. She spent a large portion of each day with her son instead of abandoning his upbringing to the nurse. And her love was not confined to her own family. She told Helen about her brother John and his wife, Louise; and the affection she felt for them and their growing family-two children, soon to be three-was very obvious.

She talked sometimes with enthusiasm and amusement about her come-out Season in London, when she had met the marquess and when his eccentric grandmother had aided and abetted their growing love and their eventual elopement. And she spoke of the people of the village of Granby where she had lived for the six years of her separation from her husband, as a governess and companion. There was no bitterness in any of these stories, but there was a great deal of affection for the people she had known. And, of course, Helen could never forget that the marchioness had saved her from a nightmare situation.

Elizabeth could also talk intelligently about books and about art. She had a great deal more knowledge than Helen, in fact, and the younger girl learned eagerly from her. The marchioness understood too that art in all its forms was more than a pretty ornament to life. Helen was playing the pianoforte in the music room one evening while Elizabeth was upstairs putting the baby to sleep. When she finally emerged from her absorption in a Bach fugue, it was to find that her hostess was sitting quietly in a chair close to the door.

"You have mastered the feeling of the music," she said. "I have heard Bach played so many times as if he wrote merely that the painist might exercise his fingers and impress his listeners. But I think you are a trifle heavy, Helen. Bach was meant to be played on a harpsichord, I believe. There should be a crispness and a brilliance about his music as well as emotion. Do try it again, but this time do not press so heavily on your fingers."

She stood behind Helen, every inch the teacher that she had been for five years. And Helen obediently played the piece again, trying to improve her technique according to the advice she had been given. It was good advice. It came obviously from someone who knew what she was talking about and who cared deeply for music.

Before many days had passed Helen was beginning to like Elizabeth Denning very much indeed.

She was also beginning to open her mind again to the events of the past few months. She had determined to avoid thinking about the painful things that had happened, but of course it is impossible to blank thoughts from the mind merely by the effort of will. When she eventually began to paint, taking all her equipment out-of-doors despite the coldness of the weather, she found she could no longer keep her feelings repressed. If she was to show feeling in her paints, she had to be willing to release all that was inside her. And the pain was with her again.

Had she been totally unreasonable? she asked herself at last. She had refused even to listen to William when he had wanted to explain why he had left her in the summer. It seemed impossible, of course, that he could have a good reason for what he had done. But then surely it would seem to almost anyone that she could not have had a good reason for allowing herself to be violated before she was married. Papa had said as much, in fact. He refused to write to her, refused to acknowledge her as his daughter or have her name mentioned in his house, her mother reported in a letter. To him there could be no possible excuse for the disgrace she had brought on herself and on his family. Papa would relent, of course, but he would never understand her behavior, she knew.

Was she being equally insensitive in refusing even to listen to William? Did she not at least owe him a hearing? After all, he was the father of the child inside her, and he had offered to do the honorable thing and marry her, even without knowing about the child's existence. His words and behavior at Richmond had even suggested that he might still care for her in some way.

What was it he had said? He had said that she behaved as if she were the only one allowed to err. She demanded perfection, he had said, and had not realized that perfection in another human being was impossible to find. Was she really being so unreasonable and so immature? She knew herself to be far from perfect. Her present condition was proof positive of that. And she had done him wrong. She had led him to believe that she was an uneducated girl of easy virtue. Certainly he had not raped her. He had, in fact, given her every opportunity to avoid his possession. She had deceived him. She should at least have told him who she was so that he could have made a free decision as she had. Was it time she admitted her guilt to someone other than just herself?

By the time she had completed her first, unsatisfactory painting of the grove of trees at the foot of the lower lawn, Helen was seeing the past few weeks in a totally new perspective. And she was no longer satisfied with her own part in those events. She really had behaved like a spoiled brat who had to make everyone else suffer because life was not going her way. She must have upset her family with her sullen ways, and she had behaved with horribly bad manners to the Hetheringtons. Even her treatment of William had been inexcusable. She was equally guilty for the turn of events during the past summer, yet she had behaved as if she were the wronged angel and he the blackest villain.

She finally came to these conclusions on the morning of the day when the Marquess of Hetherington was expected. Elizabeth had been bright with repressed excitement when Helen left with her easel and paints and paper. She must return to the house, she decided, and write a letter to William. It would be extremely difficult to write. She must apologize for her part in the predicament in which they found themselves and for her refusal to listen to his explanations. And Helen was not good at apologizing.

But who was? she thought philosophically. She packed away her painting things with a sigh. The picture was terrible. It was neither pretty nor meaningful. She would have to write, Only then, perhaps, would her conscience be salved enough that she could produce the picture that she knew was somewhere inside her. She walked back to the house to join a restless Elizabeth for luncheon.

They were in the drawing room later in the afternoon. Elizabeth was bent over her embroidery, though her mind was not really on what she was doing. It was a shame, she felt, that John had chosen to sleep longer than usual this afternoon. Playing with him would have been a distraction. Helen was seated at the farther end of the room at the escritoire, writing a letter. Whoever she was writing to, she was not finding the task easy. The surface of the desk was littered with papers that had been crumped into little balls, and she seemed to be staring at the wall ahead of her, stroking her chin with the feather of her quill pen every time Elizabeth glanced at her.

Finally, when she was beginning to convince herself with the greatest of good sense that Robert would not come today after all, but would surely come on the morrow, she heard the unmistakable sound of horses' hooves on the cobbles outside the main doors. Embroidery was dumped unceremoniously beside her, and Elizabeth was on her feet in a moment.

"That must be Robert," she said. "I should wait here, should I not, Helen? The servants will think me a mistress of scant dignity if I rush to meet him. Anyway, it is only a week since I last saw him. Is my hair tidy? The water here is so much softer than that in London. My hair just refuses to keep its chignon."

Helen turned on her chair and smiled at her hostess. It was an unusual sight to see Elizabeth agitated. "There is not a hair out of place," she said, "and I think probably servants like to serve people who show affection for each other."

Elizabeth laughed. "Your encouragement is all I needed," she said. "Helen, you are having a terrible influence on me."

And she was out of the room and flying down the staircase and across the wide hallway without a second thought to her dignity. An expressionless footman was already holding open the door at the approach of his master. Elizabeth went rushing past him and down the first six steps. Two arms reached out and lifted her over the remaining two and swung her in a wide circle.

"Hoyden!" the Marquess of Hetherington said with a wide grin. "Are you not afraid of what the servants will think, Elizabeth?"

And he was seeking out her mouth and kissing her thoroughly right there in front of the footman and the butler hovering in the background, and the groom who was holding his horse's head, and William, who was standing on the cobbles still holding the reins of his own horse.

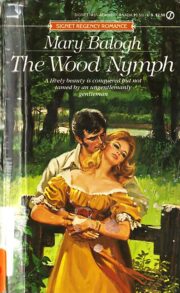

"The wood nymph" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The wood nymph". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The wood nymph" друзьям в соцсетях.