The countess clasped her hands against her breast. "You see, Emily?" she said. "I told you it must be just a matter of time before we will be accepted into the very best society. The Marquess of Hetherington! But what a pity that he is married already."

Emily said nothing, but resumed the needlework that she had put down on her father's arrival.

Helen continued to sit in the window seat, as apparently listless as she had been since their arrival in London and, indeed, for some time before that. Inwardly she was in turmoil, the blood hammering in her head so that she was totally unaware of the movement and conversation taking place in the room. William was in London! She was in grave danger of meeting him again, especially if her family became acquainted with his friend the Marquess of Hetherington. She could not. It must not happen. It was bad enough that she could not banish him from her thoughts, that she knew him to have completely ruined her life. She could not see him again. She would die if she were forced to do so.

She watched unseeing the hands that were clasped in her lap. How could she possibly avoid the meeting? Papa had said he was here for the winter. So were they. And it was inevitable that they would move in much the same social circles. Helen had none of her sisters' anxieties that perhaps they would be ignored by the ton. Her father was an earl, after all, and he and Mama had connections, neglected as they had been for several years. Sooner or later she would come face to face with William. It had been a sheer miracle that she had escaped him at home. She could not hope to do so for a whole winter here.

He would know the truth. Not that that mattered longer. She could even feel a sort of satisfaction in thinking of how surprised he would be and how uncomfortable to remember the summer. No, it did not bother her at all that the truth would be known. She felt too much contempt and hatred for Mr. William Mainwaring to be at all concerned about a little embarrassment. She could keep the anger and the deep dislike locked inside her as long as she did not see him again. But how could she come face to face with him, probably many times over the next few months, and not reveal to the whole world how strong her feelings about him were? And how could she face having to acknowledge again her own feelings of guilt and inadequacy?

How would she ever be able to be in his presence without being constantly aware of the fact that there would always be that bond between them, unwanted now by either? Had she merely loved him, she might have turned defiantly from him and lived a full life despite him. But he had possessed her, he still possessed her, and she would forever be bound by what had happened between them. She would never be free, but she certainly did not need his physical presence to remind her constantly of how foolish and how deceitful she had been. She had given herself to a shallow, unfeeling man, a man she had surely deserved at the time, and now she would have to watch him mingle with the ton as if he had every moral right to do so. Perhaps he did. She was not at all sure that his behavior was unusual for one of his class.

The Marquess and Marchioness of Hetherington did indeed make the promised visit the following afternoon. They were not accompanied by William Mainwaring, to the satisfaction or relief of most of the family of the Earl of Claymore. As they left, the regulation half-hour after their arrival, the marchioness placed in the hands of her hostess an invitation to a ball they were to hold the following week.

"It is not to be a large affair, ma'am," she said. "This Is not the Season, and London is not as heavily-populated as it will be then. But our mutual friend, Mr. Mainwaring, is newly arrived and we have planned the ball as a welcome to him. I am sure he would be delighted, as we would be, to see some of his neighbors there. I do hope you will be able to come." She followed her husband from the room after smiling warmly at the countess.

"Robert," she said as she sank into the warm velvet upholstery of their coach and made room for him beside her, "I am so glad you suggested that we visit the earl and his family this afternoon. They seemed almost pathetically grateful to see us."

“I could hardly say no, my love," the marquess said, turning to her with a grin, "when the man himself suggested it at White's yesterday. William had a previous engagement but I had none. But you are right. They have rusticated so long, I believe, that London is like a foreign city to them. You see the dangers of staying in the country for too long, Elizabeth?"

"Oh, well and good," she said, "but you know that once John is past babyhood I wish to spend most of our time in the country, Robert."

He leaned across and kissed her lightly on the lips. "And you will hear no argument from me," he said. "There I shall have you more to myself."

"Robert," she said seriously, a frown creasing her brow, "is it possible to help William become attached to any female? He seems to have been quite impervious to the charms of any of the ladies he has met in the past week or so."

The Marquess of Hetherington laughed and took her hand. "Elizabeth, I quite forbid this train of thought," he said. "William is a grown man, you know, older than either you or I. Let us leave him to manage his own life."

"But he cannot be happy, Robert," she persisted. "There must be someone worthy of him. Do you think he became well-acquainted with any of the earl's daughters during the summer?"

"I doubt it," he said. "I don't think any of them is quite William's type. The oldest one is too haughty for her own good. The middle one is shallow, if I may judge on such short acqaintance. And the youngest one… well, what did you think of the youngest one?"

Elizabeth looked at him. "Oh, Robert," she said, "I do hate to be unkind. But was she not dreadful? No looks. No manners. No personality. I feel quite sorry for the girl."

"I found her quite fascinating," Hetherington replied, and he grinned as his wife looked at him, eyebrows raised. "I do believe this afternoon was the first time I have ever seen you fail miserably to draw someone into conversation. Did she actually growl at you, my love, or did it merely appear that way from across the room?"

"She certainly scowled when I tried to commend her on her embroidery," Elizabeth said.

Hetherington leaned toward her until their shoulders touched. "I do not know why we are wasting time on such topics," he said, "when we are all alone together in such a setting, Elizabeth."

"Oh, do behave yourself," she said with a most unladylike giggle. "We are in the streets of London, Robert, not far out on an empty highway."

He sighed. "Even there, you always seem to be terrified that a highwayman or someone will poke his head through the window at some intimate moment," he said. "Not that that ever particularly deterred me, did it, love? It is still my theory that John was conceived on the road to Devonshire."

"Robert!" she said, her face and neck almost crimson. "You know I do not like you to say so. And I am sure it is not true. Oh, do stop it." She slapped ineffectually at his hand, which had already undone the ribbons of her bonnet and was pushing it back from her head. "Have you no shame?"

"None whatsoever, my love," he said, and he grinned down into her flushed face before lowering his mouth to hers.

Chapter 9

William Mainwaring propped one foot with its silver-buckled dancing pump against the cushions of the seat opposite him. He had drawn the velvet curtains across the carriage windows. Although there was always plenty of light in the main streets of London even at night, he had no particular interest in viewing other partygoers. He rested an elbow on a satin-clad knee and smiled. Really, he marveled, he felt happier than he had felt in a long while.

He knew the reason for this ball, of course, as he had known the reason for the two informal dinner parties that the Hetheringtons had held in the two weeks and since his arrival in London. Elizabeth was trying to matchmake. Robert had even admitted as much a few mornings before, when the two men were riding alone in the park. He had expected to feel more anguish at the realization. He had even gone home after the ride instead of accompanying his friend to Tattersall's, so that he might examine his bruised heart in private.

And it was there, quite alone, that he had discovered that there was no very painful bruise, only amusement that a woman several years his junior, a woman who had once agreed to marry him, had taken it upon herself to find him a wife. He did not love Elizabeth any longerl That is, he had been hasty to remind himself, he loved her a great deal. None of his admiration for her serenity and her intelligent good sense, and none of his appreciation of her beauty had faded. He still felt his heart lift in her presence as he always had. He still considered her one of the closest friends he had ever known. But he no longer felt about her as a lover feels.

The knowledge had come as a great shock to him. He had taken for granted that that type of love could never die. When he had first met her again-dreadful afternoon-all the pain of his brief courtship and of its abrupt end had flooded back and the wound had been as raw and as painful as it had ever been. She was more beautiful than she had been, if that were possible. Now there was an addition to the serenity that he had always loved. Now there was a radiance, and it did not take much imagination to know that it was Robert who had wrought the change. If he had ever doubted the true feelings of those two for each other, he could doubt no longer after seeing them together. They did not display their love in public, but they did not need to. They glowed.

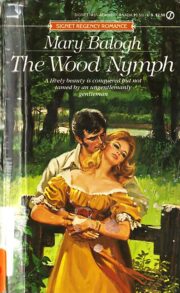

"The wood nymph" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The wood nymph". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The wood nymph" друзьям в соцсетях.