For the first time, Mainwaring admitted to himself that he was probably far better off away from Elizabeth. It had been a bad year, but the worst of the pain had dulled. There was just the ache left, the knowledge that his whole life was spoiled by what had happened. But he pain would have been constantly present, the wound would have festered, if he had been daily in a position of intimacy with her.

He could not put Nell in that position, Nell was a free spirit. He would not be able to bear to see the light go out of her eyes and the spring from her step. He could not imprison her soul. She would suffer if he left her. In all probability, if her feelings ran deep, as he suspected they did, she would be badly hurt for a long time. But she would still be free at the end of it all. She would probably be a stronger person for the suffering.

There was only one thing that he could do. Much as he disliked having to uproot himself yet again, admit defeat once more, he must leave. If he stayed, he was not sure that he would have the strength to stay away from her. And even if he did, it seemed very possible that he would run into the girl in the village one day. Even the knowledge that he was still in residence would cause her unnecessary pain. He must leave and give her a chance to begin forgetting him.

He did wonder if it was the honorable and the compassionate thing to do to go to Nell the next day and tell her of his decision. He could imagine her perhaps going to the woods for several days before she heard of his departure, waiting for him to come. He could imagine her pain when she discovered that she had been abandoned without a word. He would look the biggest blackguard ever to walk this earth. But equally he could picture the scene if he faced her with the truth. Would she be saved any pain by his presence? Perhaps it would be worse. And, worst of all, perhaps his pity would overcome him and he would take her into his arms again. There was no saying what would happen if he did that. But the end result would still be the same.

There was not much rest that night either for Mainwaring, or for his servants. He wrote notes to all his acquaintances in the area, excusing himself for his hasty departure. He wrote longer letters of apology to the two families with whom he had accepted invitations. His servants packed his bags and prepared his curricle and his horses.

Thus it was that early the following morning William Mainwaring was on his way to Scotland, all but his heaviest trunks strapped to the back of his curricle. His heavier luggage was to be sent on later. It was with a heavy heart that he drove on until the landmarks became unfamiliar. This was a sordid and a shameful episode of his life, and he would not easily forget it. One's own unhappiness was easier to bear than the unhappiness one knew one had inflicted on someone else.

The family was already sitting down to dinner when Helen trailed into the dining room. She took her place without a word.

"Well, miss?" the earl said severely. "Is it customary in this house to come to the table whenever you feel like doing so?"

"I am sorry, Papa," she said. "I was busy thinking and I forgot the time. I did hurry as much as I could so that I would not be dreadfully late."

"Perhaps a removal to the schoolroom without any food or drink would teach you that punctuality is a virtue in this house," her father said.

"Yes, Papa," she replied, her eyes on her empty plate.

"And next time, child, that is exactly what will happen," the earl blustered, unnerved by the docility of his daughter.

"And where were you this afternoon, Helen?" her mother wanted to know. "You know very well that I asked specifically that you drive to your Aunt Sophie's with your sisters and me. It was Cousin Matilda's birthday, and it was only fitting that we all go to wish her a happy birthday."

"I am sorry, Mama," Helen said. "I forgot. I went for a walk."

"There have been altogether too many walks since spring arrived this year," the countess said in exasperation. "Papa and I have been very patient. We know that you are rather strange, child, and that you seem to need to be on your own more than Emily and Melissa. But, really, at your age, you must begin to take an interest in your social duties. If you cannot limit the walks to afternoons when we have nothing else planned, I shall really have to forbid you altogether to leave the house unaccompanied."

"Yes, Mama," Helen answered meekly.

Really, she did not feel like arguing with anyone. She felt mortally depressed, though she had told herself for the past two hours that she was overreacting. William had not been there this afternoon. There was nothing so strange about that. He felt his social obligations, even if she did not feel hers. He was very popular in the neighborhood. Doubtless he had other engagements for the afternoon. She could not expect to see him every day. Tomorrow he would be there.

She must be very careful not to antagonize Mama further. What a dreadful predicament she would be in if her mother's threat were carried out. Not that her parents usually showed such consistency, but she did not want to tempt fate. She would never be able to see William if a groom or a maid were made her constant watchdog.

It would not be so bad, perhaps, she would not be so depressed, if she had not had a presentiment that he uld not come today. She had sat under the oak tree trying to shelter from the chill wind that had arisen since noon and had known that she would not see him. She told herself now, as she had told herself all afternoon, that he would come tomorrow and all would be well. She had nothing to fear until then. They had no engagement for that evening, which might have brought her unexpectedly into William's company.

Helen was so deeply wrapped in her own gloom that she almost missed the interchange between Melissa and her mother. Melly was talking in her complaining whine, Helen's unconscious mind realized, before her conscious mind heard the words.

"But, Mama," Melissa was saying, "I cannot believe that he would have left without a word. Surely something dreadful must have happened to cause him to leave in such a hurry. We were to ride one morning."

"It is most provoking," the countess agreed. "He did appear to show a marked partiality for you. It must have been your excessive modesty, my love, that made him believe that you did not wish the connection. I cannot think what else can have changed his mind."

"Perhaps he thought that because he was a mere mister, he was not good enough for me," Melissa said tragically. "Oh, Mama, what am I to do? We will never find husbands."

"Considering that he is so beneath us in station," Emily added tartly, "I would say that Mr. Mainwaring altogether put on too many airs. He is probably holding out for a duke's daughter. I warned you, Melly, how it would be."

Helen was all attention now. "What has happened to Mr. Mainwaring?" she asked.

"You see, Helen," her oldest sister said crossly, "you will have nothing to do with visiting with us, and then you expect us to relay all the local news to you at the dinner table. Mr. Mainwaring has gone, that is what has happened. The neighborhood is buzzing with the news. He gave no warning, you know, and he had several invitations that he had to decline after already accepting them. For once I must applaud you, Helen, in showing no interest in securing an introduction to the man. He did not deserve such notice."

Helen felt somewhat removed from the scene at the table. Her ears were buzzing. Voices seemed to come from far away.

"He is not much loss to the neighborhood," the earl grumbled into his food. "The fellow's just a city dandy, if you ask me. Won't hunt because of the poor fox! Won't watch a cockfight because of the poor birds! It only made me wonder that he did not carry a jar of smelling salts around in his pocket."

"Is he not coming back?" Helen asked. Her voice sounded surprisingly normal to her own ears.

"It seems not, child," the countess said. "In the note he wrote Papa, he explained that he is going to Scotland for the remainder of the summer at least. And his trunks and boxes were sent away from Graystone this morning."

"Oh, Mama, what am I to do?" wailed Melissa.

"Don't fret, my love," Lady Claymore said. "I talked to Papa earlier about going to London perhaps for the winter. It is only right that you girls should have the opportunity to find husbands worthy of your rank and breeding."

"Mama?" Emily looked sharply at her mother, hope dawning in her eyes. "Is this right?"

"Well," the countess said, glancing anxiously at her husband, "Papa said he would see."

Emily talked about nothing else for the remainder of the meal. It was quite beneath her sense of dignity to appear too enthusiastic about the proposed visit, but it was obvious to all that she was very eager indeed to go to London. Even Melissa's mood seemed to lift somewhat when she was reminded of all the parties and entertainments that winter in the city would have to offer. Why, the place must be simply teeming with gentlemen equally as handsome as Mr. Mainwaring, and a good number of them might even have titles.

Only Helen's mind refused even to consider the delights that might be in store for her if only Papa would agree to let them go. She could not think beyond the dreadful fact that she had been abandoned, left without a word of explanation, by the man who had become her lover. She sat rigidly in her chair while the animated conversation of her mother and sisters continued. She ate without even realizing that she did so.

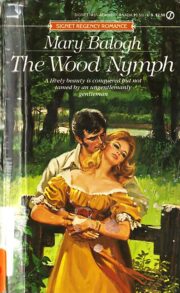

"The wood nymph" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The wood nymph". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The wood nymph" друзьям в соцсетях.