Had he said he would come back tomorrow? Had he said anything about seeing her again? He had said he would hear what she had to say the next time, but he had not said when that next time was likely to be. Absurd to worry about that. They had met enough times, and knew each other well enough that they no longer had to make definite arrangements to meet again. He knew that she came here very often in the afternoons. He would come tomorrow, or at worst the next day. Had he not said that he had missed her? And had not his lovemaking shown a very definite regard for her?

Helen turned around with sudden impatience and pulled her dress over her head again. She tossed it down on the grass and jumped into the stream. The water reached to her waist, and she gasped with the shock of its coldness against her heated flesh. Then she took a deep breath and plunged beneath the surface, trying to wash away her uneasiness along with the dried sweat of summer heat and an afternoon's passion.

Chapter 7

It was really a crime that one did not get up early every morning. William Mainwaring thought as he drove his curricle along dusty country roads, expertly maneuvering it around bends that would have taken an inattentive driver quite unawares. There was a quiet and peacefulness about the early morning that was not there later in the day. The sun was still quite low on the horizon, and a haze still settled over everything, promising heat again later. But for now, the air was fresh and cool. He felt almost cheerful for a brief few minutes.

If only he did not feel quite such a failure. It seemed to have become his fate in life to be constantly running away. When he had left Scotland a few short years before, he had thought he was running to life, a life that had passed him by for the whole of his youth. But what had the adventure brought him? Last year he had fled from Elizabeth as soon as her husband made it clear to him that he would not easily leave her go. And he had left London just a short while ago, convinced that he would be happy again in a country setting.

And now here he was again, running back to Scotland because of a little wench whose parents could not afford to buy her a dress that fit or shoes for her feet. Would he ever find a place where he belonged? Had he merely been unfortunate in his relationships, or was there something wrong within himself? He sighed. His housekeeper in Scotland would be surprised to see him. He would probably throw her into fits. His grandfather's old housekeeper had survived him by only a couple of years, and Mainwaring had hired this woman shortly before his departure for London. He assumed that the household was running smoothly, but he did not know how the woman would react to his unexpected arrival.

His decision had been made the evening before after a great deal of soul-searching. He had tried to shrug his mind free of Nell. She was, after all, a creature of no social significance. She had given herself to him entirely of her own will, and she had been foolish enough to fall in love with him. She could not expect anything more of him than some money with which to buy herself decent clothes. Or perhaps she hoped that he would set her up as his mistress. Such arrangements were not at all uncommon. But really he owed her nothing. He could salve his conscience quite easily by going to her the next day and giving her a bag of coins. It was as easy as that.

The trouble was that it was not at all that easy. He had never been able to think of people solely in terms of class. It had appalled him in his time in England to notice with what indifference, even contempt, the people of his class could treat their servants. And women always suffered the most. He had been at one houseparty when he had literally bumped into a maid one morning as he left his room. She had been sobbing into her apron, but would not answer his queries. She had merely rushed past him. Later in the morning, the other members of the party, all male, had roared with appreciation as one of their number had described in graphic detail his rape of the girl the night before. Mainwaring had left the house the same day.

No, he could not dismiss Nell from his mind merely because she was of a lower class. She was a creature of intelligence and sensitivity, he knew, and a woman of deep feeling and passion. If it was true that she loved him, she would suffer when she knew that he did not return her feeling, that he had no intention of making of their relationship anything more than it was at present. She would be hurt, perhaps permanently scarred.

And he knew very well how she would feel. The same thing had happened to him the year before. And there was no worse feeling in this world, he believed, than to know that one's love was bestowed where it was not returned and that there was no hope of any change. The one difference was that Elizabeth had been far more honest with him from the start than he had ever been with Nell. He had fallen in love with Elizabeth, knowing full well that she did not love him. She had never encouraged him, never given away physical favors except that one kiss after he had finally persuaded her to marry him.

He had behaved deceitfully and dishonorably with Nell. Although he had never spoken words of love to her, with his body he had led her to believe that he loved her. He had taken possession of her body twice, taken the privilege of a husband, even though he had had little doubt the first time that she was a virgin. It was no consolation to him that the vast majority of men of his class would have done the same without the merest qualm of conscience. He was not other men. He m as himself, with his own very strict code of conduct and his own very tender conscience. She had every right to love him and feel secure in the expectation that he returned her love.

As he sat in his library alone, not even a drink in his hand to dull the edge of his guilt, Mainwaring felt very ashamed of himself. He had not forced her, it was true. She had made her own decision to allow him to possess her. But he could not excuse himself with such thoughts. He should never have allowed himself to touch any woman unless he was prepared to offer his heart as well as his body.

What was he to do? He could not continue the affair; that much was perfectly clear to him. He would not offer her compensation in the form of money or gifts. He would feel it insulting, and he had a strong belief that Nell would feel doubly hurt if he tried. It would be like offering her payment for services rendered. He would be making a whore of her.

What, then? Mainwaring sat for a long time, an elbow resting on one raised knee, staring into an empty fireplace, wondering whether he should marry the girl. The possibility would not have occurred to most men in his position. Even to marry a governess or the daughter of a cit would have been beneath the dignity of any but those very much in love or very much in debt. But to marry a little nobody who did not seem even to possess a pair of shoes would have seemed downright laughable. And why marry a wench who gave freely outside the marriage bed?

But to William Mainwaring it was a very serious problem. He cared not a fig for social convention. It mattered not to him that if he married Nell, half the drawing rooms in the country would be closed to him. He had no particular wish to enter those drawing rooms. The only questions that did occupy his mind were whether or not he should marry her or whether marriage to him would be the best solution for Nell.

There was really little doubt about the first question. He owed her marriage. He had perhaps taken away her chances of making a decent marriage with any other man. At best, he had placed her in danger of being very severely punished by a future husband who would discover that he was not the first to use her. He could have paused at that point and made the firm decision to make Nell his wife. He would not suffer unduly from the marriage, even if his own happiness mattered in this decision. He liked her and found her attractive. What would it matter to him if he did not love her? It was not as if he expected someday to find a bride whom he could love.

But it was the second question that he pondered long. If she did love him, Nell would be happy to marry him. Her life would change a good deal, suddenly she would be able to have all the things she had only dreamed about. And he would enjoy spending money on her, seeing her childlike delight in the gifts he could give her. Yet was it certain that marriage to him would bring Nell happiness even if he could disguise the fact that he did not love her? Even if their social life was restricted, her life as his wife would be vastly different from anything she had known. And must he assume that the change would be all for the better? She would find the adjustment a gainful process no doubt. She had no training whatsoever for that life she would have to lead.

Marriage was for a long time. All else notwithstanding, it would not take Nell long, sensitive as she was, to realize that his feelings for her in no way matched hers for him. He would not be able to pretend for a lifetime.

And it was on this point that the whole decision hinged. Would the unhappiness of being married to someone one loved but who did not return that love be worse than that of being completely abandoned? A year ago he had pleaded with Elizabeth to marry him, even though she still loved Robert. He had enough love for both of them, he had assured her. And he had believed passionately what he had said. Now he was not so sure. If Robert had divorced her, and if she had married him, would it be torture now to be here with her, seeing her every day, loving her by night, knowing that her heart was somewhere off with her first husband?

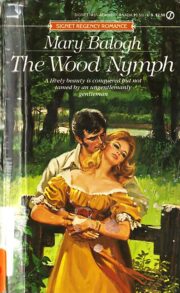

"The wood nymph" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The wood nymph". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The wood nymph" друзьям в соцсетях.