She was still thankful that he had not been at the ball. It would not have been a good setting for such a discovery. But she would tell him the next time they met. It was a great trial to know that it would not now be the next day or the day after. It might be a week or more before he was able to walk to the wood again. But he would go there as soon as he was able, she knew, and there she would tell him the truth. He possibly would be angry at her deception, and embarrassed, but all would be well. In fact, once he had got used to the idea, he would probably be glad to know that she was a girl of his own social level. They would marry.

It was a pleasant dream, one that sustained Helen through what remained of the night. She slept peacefully after ten minutes of wondering if William were in pain and unable to sleep himself.

William Mainwaring had, in fact, spent an almost sleepless night. He would never have guessed that a simple sprain could hurt as if it were a dozen fractures. Of one thing only he was thankful. No one knew the truth of how he had sustained the injury. He felt a prize idiot. He had been behaving like a young boy with his first infatuation. In fact, embarrassing as it was to admit even to himself, that was more or less what he was. His very retired upbringing had retarded his social progress by at least ten years. How most of his contemporaries would snicker if they knew that yesterday afternoon, at the age of one-and-thirty, he had bedded his first woman!

And now he had made very sure that the affair would not continue for at least four or five days. He ground his teeth as he was forced to accept the support of his valet down the stairs to the breakfast room. He had refused to stay in bed. The sun was shining with every bit as much force as it had the day before. He ached to be with Nell again. He wanted to make love to her. He wanted to touch her warm and pliant little body again. He wanted to be inside her.

He took the plate of food that the butler had heaped for him at the sideboard and turned his attention impatiently to the pile of mail at his elbow. There was no point in brooding on what could not be. But how provoking it was to think that she would probably be there waiting for him. It was unlikely that she would have heard about his mishap. Would she think that he had abandoned her, that having once tasted of her treasures he had lost interest? He would have to make it up to her when he saw her next.

His attention was arrested by a letter that had been addressed in an unmistakably feminine hand. He felt himself turn cold. What other woman could be writing to him but Elizabeth? He tore open the seal and spread the letter on the table before him, his food forgotten. Yes, it was indeed from her, he saw, glancing to the signature at the end. He had not seen her handwriting before, but he would have known that it was hers. It had all the neatness and elegance and restraint that were so much a part of her character.

They had received his letter, and it had been a relief to them to know that he had finally received one of theirs. It was an equal relief to know that he had not received any of the others. His long silence was now explained.

"I have so much wanted to write to you myself," she wrote. "I have always felt very badly about what happened a year ago, William. I am afraid I presumed too much on a friendship that I held, and still hold, very dear. I should never have agreed to marry you. Indeed, I do not believe that I would have wronged you to the extent of going through with the ceremony, even if Robert had not acted as he did. And it would have been wrong. You knew that I could not have given my heart to you, and you very much deserve to have a wife who is wholly yours. You are a very dear person, William."

The letter went on to repeat the invitation that her husband had extended in the earlier letter. It also told the news of the birth of a son two weeks before.

Mainwaring let the letter fall onto the table when he had finished reading it. He felt sick. He pushed aside the untouched plate of food and pushed himself to his feet. Then he winced and sat down again with an oath. He was forced to accept the butler's assistance to the library, where he sat, his injured leg propped on a stool, staring sightlessly out of the window.

He relived all the pain and the loss of the previous summer as if those events had happened but yesterday. Those first weeks in London had felt like hell itself. He had wandered around restlessly, contented nowhere, avoiding acquaintances, trying to decide whether he should write to her or not, whether he should try to see her or not. She had promised to marry him if he could free her from her existing marriage. And he had been so confident that Robert would raise no objection to divorcing her. He had been so sure that Robert had no feeling for her after having lived apart from her for six years. It was hard to accept the sudden reality of being alone, exiled from her. He had wanted to go to her. He was not sure that she did not wish to see him. But his powerful sense of honor had kept him away. Her husband had refused to set her free, had warned him off, and he had to accept the rights of a husband.

But he had ached for her, as he ached for her now. Elizabeth, with that rare aura of tranquillity that attracted all who knew her. He doubted if she fully realized how much she had been respected and loved by all the families around Ferndale, even though they knew her only as a paid governess and companion. He could not blame Robert for refusing to give her up. It only seemed incredible to him that he had been able to live apart from her for all that time, when they were legally married. But there was obviously a very interesting story surrounding that mystery, a story that he would never know.

Damn Robert Denning! If only she had never met him, perhaps she could have loved him, William Mainwaring. Perhaps they would have been married now and it would have been his child that she had just borne. Foolish thought! He put his head back against the rest of the leather chair in which he sat and stared at the ceiling. If she had not met Robert, she probably would not have ended up in the vicinity of Ferndale as a governess. And she would perhaps have been a different person had she not suffered in the past. In fact, he remembered saying something like that to her when he was trying to persuade her to marry him. No, things were as they were and he would have to learn to live with them.

He closed his eyes. How could he so have forgotten his love as to have become excited by that little wench in the woods? He compared the two women in his mind. Elizabeth, so mature; Nell so childlike. Elizabeth with her beauty, her charm, her social poise; Nell with her wild, untutored grace. Elizabeth's intelligence and good education; Nell's ignorance of all except the wild nature around her. Elizabeth, perfectly groomed and elegant; Nell, shabby and unkempt. How could he have? How could he have so forgotten Elizabeth yesterday as to have violated Nell and even convinced himself that it had been a good experience?

He felt repelled now by the memories. How could he have convinced himself that the girl was a sweet innocent? She was wild and promiscuous. True, she had been a virgin before he had touched her, but it was just pure chance, surely, that he had been the first. The girl would have done as much with any male who happened to come her way. What modest wench spent a great deal of her time alone in the woods? What modest girl offered such an open invitation as a shabby dress that was too small for her and that revealed a considerable expanse of bare leg? He was suddenly glad of his sprained ankle. It offered him the excuse he needed to keep away from his appointment with her. By the time he was recovered, she would have forgotten about him, in all probability. She would probably have found someone else.

Mainwaring was given little more time to brood that day. Although unable to go out himself, he found that almost every man of rank for miles around called on him during the day to inquire about his health and to commiserate with him for having to miss the several entertainments that had been arranged for the coming days.

Chapter 6

The following five days were dreary ones for Helen. She lived in a state of almost unbearable tension. Her last meeting with William Mainwaring had begun something which it was a torture to have to delay. Had she only been able to see him on the following afternoon, all the joy and the excitement of being in love and of sharing of physical relationship with her lover might have been sustained. But she found that as the days crept past she became less confident, more shy of seeing him again. Perhaps for him it had all meant nothing. Perhaps he was accustomed to such encounters. But no, she would not believe it. He must love her as she did him.

She knew from her father's conversation that Mr. Mainwaring was likely to be house-bound for a week. Apparently his leg was badly sprained and he found it quite impossible to put it to the ground. She felt quite safe, therefore, when she returned to the woods two days after his accident, in bringing her books and her paints out of the hut. She decided to paint the stream at last and spent a half-hour vainly trying to capture on paper all the shades of color and light that she had observed the afternoon she had first met William.

She finally gave up the effort in disgust. What she had painted on the paper in no way resembled what she saw in her mind. She could force no communication between mind and hand. Of, of course, she knew the reason. She knew from long experience that she could never produce anything to her satisfaction unless her whole mind was absorbed in the task. And she had not fully concentrated on her painting that afternoon. She was thinking of William. She was wanting him.

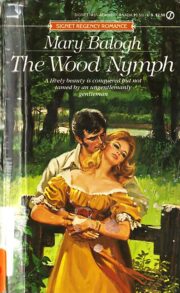

"The wood nymph" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The wood nymph". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The wood nymph" друзьям в соцсетях.