It took him well over an hour to reach home, and another half-hour for his valet to remove his boot from a foot that had swelled alarmingly around the ankle. He was forced to agree reluctantly to sending a groom in search of the doctor. The ankle could be broken, and the sooner it was set, the better it would heal.

There was no broken bone, only a bad sprain, but before the evening was half over Mainwaring was forced to realize that he was going to be house-bound for the next few days at least. No ball at Lord Graham's tonight. No ride with Lady Melissa one morning in the near future. And no lovemaking tomorrow with Nell.

Helen was dancing with Oswald Pyke. It often struck her as a great blessing that she was not as smitten with him as he was with her. Even if she were head over ears in love with him, she could never bring herself to marry that name. Imagine being Mrs. Oswald Pyke. Helen Pyke. Master Egbert Pyke, Miss Georgiana Pyke. And all the little Pykes. Fortunately, it was no great sacrifice to refuse him just on the grounds of a ridiculous name. She liked the man no better.

It was not just his looks, though she found nothing attractive in his short, rather pudgy figure, his thinning fair hair, and his plump hands that always seemed to be moist. He was a bore. If it were not his hounds he was talking about, it was his crops or his new hunting jacket or some other topic of no possible interest to her. Or else he was proposing marriage to her, one of his favorite hobbies. He was doing that now, despite the fact that it was the opening set of the ball and despite the inconvenience of the fact that it was a country dance and they were frequentlyy separated by the figures of the dance. Every time they came together for a few seconds, he was at it.

"If I have a good crop of turnips this year, I shall be able to afford a new ladies' maid," he said. "She could be assigned wholly to you if you will marry me, Lady Helen."

They were separated by the dance.

"Do give me an answer," he begged the next time they came together. "Do not keep me in suspense like this."

"I have told you at least fifty times, Mr. Pyke," she replied, "-or is it fifty-one?-that I will not marry you. Or anyone else at the moment," she added when she saw his crestfallen face as he turned away to twirl with another lady belonging to their set.

She answered mechanically. One did not even have to listen to Oswald. He rarely had anything new to say. She even danced mechanically, her mind and her eyes on the doorway into the ballroom. Any second now he would appear. Already he was late. Melly was fuming on the sidelines. Anyone who did not know her might not know that she was angry, of course. She smiled with dazzling brightness and her fan was waving at a sprightly pace. One of her feet kept time to the music. But Helen knew that she was furious. She had refused more than one partner on the grounds that the set was already spoken for, and now she was left standing like a wallflower.

But Helen had little sympathy to waste on her sister. Her heart was beating like a sledgehammer on her own account and she was in danger of losing her step every time someone new appeared in the doorway. For how long after his arrival would she be able to escape his notice? On the way here in the carriage she had been cautiously hopeful. Surely if she were careful enough, she could keep the length of a room between them for the whole night. The weather was warm. She could perhaps persuade her partners to take her walking in the garden.

But she knew it was hopeless as soon as she arrived. She had forgotten how small the Grahams' ballroom was. The man would need two cataracts not to see and recognize her even if they were squeezed into opposite corners of the room. She would try, of course, but she knew it would be no good. And she dreaded the moment when their eyes would meet and recognition would dawn in his. What would she do? Smile and wave? Blush and bite her lip? Walk over to him, hand extended in sociable greeting? Rush crying into the garden? Swoon? Well, she would soon find out, she thought gloomily as she and Oswald came together again and he renewed his persuasions.

When the set ended, Helen crossed to the French doors and stood against the heavy draperies that had been drawn back from them. If she stood very still, perhaps she could blend into the background. Her gown was not a very different shade of primrose from the curtains. She watched the doorway to the ballroom as if she expected her executioner to come through it at any moment.

She had tried to avoid the meeting. She had never been very good at faking a cough or a sneeze. She had had to use the headache story again. But no one had believed her.

"Nonsense, child," Mama had said, looking impatiently at the drooping eyes and wan expression of her youngest daughter. "It is a very strange headache that attacks only when there is some entertainment approaching. You always seem in bouncing health when you leave the house in the afternoons for one of your walks or rides."

"How strange you are, Helen," Emily had said. "Have you no interest in elevated company and superior conversation? Why must you always try to avoid any activity in which you must meet people-and the best people that this part of England has to offer, at that?"

"You are going tonight and that is that!" the earl had said, and Helen could tell by his tone that there was no point at all in trying to argue further.

She had wanted nothing more than to crawl to her room, where she might spend the evening and the night digesting what had happened that afternoon. She could not yet feel any guilt, and surely she should. All she could think of was the terrible disaster of the ball tonight that would prevent her from ever meeting her lover again and experiencing the great happiness of making love with him once more.

"Oh, yes, it would be my pleasure," she said now with a wide smile as another young man of her acquaintance bowed before her and solicted her hand for the next set. And another for the next. By the time the music began for the fifth set, the one before supper, Helen found herself tense with hope. He was not going to come! It was incredible. He must know that the evening had been arranged for his benefit, the Grahams having a marriageable daughter, whom a Season in London during the spring had not succeeded in removing from their hands. He must realize that he would be committing an unpardonable social sin in omitting to put in an appearance. Yet surely he would be here by now if he were coming at all.

It was only well after supper, when Helen was flushed and delirious with joy, dazzling her present partner with her vitality, though she did not realize the fact, that she discovered that Mr. Mainwaring had sent his apologies to his hosts early in the evening. He had a sprained ankle and was unable to walk.

"You see, child," her mother pointed out wisely during the journey home, interrupting a loud and excited monologue that Helen was delivering to no one in particular, "if you just make an effort to go out and mix with people, you find that you enjoy it. I have not seen you so happy for a long time."

"I don't know how you could have enjoyed yourself so much, Helen," Melissa complained. "I thought it a particularly insipid evening."

"Indeed, it was most disappointing to learn that Mr. Mainwaring has injured his leg," her mother agreed. "I hope it does not confine him to home for many days. His presence has certainly livened up the neighborhood in the last weeks. It will be most disagreeable to be without him."

Helen sat quietly for the remainder of the journey home and retired meekly to her room when they arrived there. The great sense of relief that had succeeded upon the realization that she was to be reprieved for that night at least was already wearing off. If it was not now, it would come later. And William was hurt. What had happened? Was he in a great deal of pain? She would be quite unable to see him or even to make inquiry about a man she was supposed not even to have met. She would have to rely solely on the chance mentions of him that her family or their acquaintances might make. And his leg might be broken, for all she knew.

William. She whispered the name. It had never been one of her favorites. She had never thought of it as a particularly romantic name, though it was shared by one of her favorite poets. But how dear the name sounded now, evoking as it did the face and figure of her lover. Helen sat cross-legged on the bed, clad in her nightgown, and allowed her thoughts to dwell fully on him, as she had not dared since she had left that afternoon.

She tried to feel shame. She told herself quite deliberately what it was she had done. She had given what no lady dare give outside her marriage bed. With a man she scarcely knew and one who did not know her true identity, she had lain in broad daylight on the grass and made love. Yes, it was an apt expression. They had made love. He had been very tender and considerate.

She remembered how he had given her a chance to stop what was happening between them before any real harm was done. And she remembered how, after it was all over, he had lain beside her, his arm beneath her head, and held her close, his free hand stroking her head until he fell asleep. And after he had dressed and prepared to leave, he had taken her into his arms and kissed her and made her promise that she would come again the following day.

Yes, of course, now that she could think about the afternoon, she could recognize that he loved her too. He had not been a man merely taking advantage of a willing wench. He loved her! She really need not be afraid to tell him who she was. How could he despise her? There had been nothing sordid in what they had done. He would realize that, would know that she was not normally loose in her morals. He would know that she had given him all merely because she loved him.

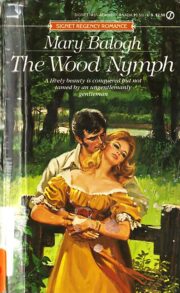

"The wood nymph" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The wood nymph". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The wood nymph" друзьям в соцсетях.