After a while he spoke, and listening to his words within the concavity of his chest was, to Martha, like hearing a mine shaft closing in on itself.

“I had fought for seven years as a soldier for Cromwell, killing my own countrymen; killing a man who had been king. I thought I’d seen every base thing a man could do to another. But in this I was wrong. I was sent by Cromwell to Ireland to help crush the Catholic rebels. Those that threw down their weapons were murdered along with the ones who refused to surrender. The resisting were burned alive in their churches; priests spitted like spring lambs in the marketplace, women raped while lying over the bodies of their children, babes dashed to the stones.”

She stirred against his ribs as though in protest but he quieted her, shushing her like an infant, and went on.

“I was sent out to a settlement hard by a town called Drogheda to clear out the miserable hovels there. Not even proper houses but caves dug into hillsides covered over with daub and thatch. From the last hovel a man, wearing no more than a linen shift and felt-tied boots, reared himself from his nest, slashing at my arm with an old clannish dirk. I’d never seen a man so wild in his attack. I killed the man but kept to this day his dirk to remember that a man is most savage when fighting for his home.

“It was then I heard a child’s wail coming from inside the cavern. There was no door, but a sheep’s hide covering it. I crawled into a chamber, smoked and reeking of death, and spied a small boy, no more than four years old, clinging to the body of his mother. She had cut her own throat rather than be taken by us.

“I have seen harried deer with less fright than was there in that boy’s eyes. I sheathed my sword and held out my hand to him. He bared his teeth at me, for he had been told by the Irish priests that the English would eat him. The boy believed I’d tear the flesh from his bones for my supper, and he took the knife with his mother’s blood still warm on it, and brandished it at me.

“For an hour or more I spoke to him, of cattle and fields and harvesting grain. And even though I did not speak his Irish tongue, my own good Welsh is drawn from the same well. I told him of my brother, gone from the earth. I told him of my own son just his age, and after a time he crept towards me and fell onto the bread I had offered. When I left the hovel, he followed after.

“From that day forward I thought I was done with killing, and when my wound grew rank and would not close, I was mustered out and sailed for England with others whose limbs could not fester, for they had been hacked off, by Irish rebels or English surgeons. I did not learn of my family’s death till I returned to London. They had been dead near three months.”

He paused, inhaling deeply as though the air had thinned, settling his chin more heavily on the crown of her head. His fingers dug into her, and she held her own breath, willing herself not to flinch under his hands so that he would go on.

“My wife, Palestine…” His voice thickened for a moment. “My wife died for a man named Lilburne, leader of the Leveller cause, put in the Tower for preaching the rights of men. Petitioning for his release, she challenged Cromwell himself in front of the Hall of Commons. She caught his cloak, calling him to task for killing the king and jailing people of goodwill. Can you imagine it? A man who was like a king himself, called to task by a girl. There was not a man living who dared put hands on the Protector, but my wife dared. By Christ she did.” A brief exhalation of air, coarser than a laugh and more prideful, passed through his lips. She felt a lightning stab of something close to jealousy but willed it gone before he could feel it through the crown of her head like a fever.

“It was Cromwell’s men who jailed them, taking my wife and son to the Tower. The bastards had waited till I was shipped for Ireland. They meant only to frighten her, to stop her from calling Cromwell to task for becoming a tyrant himself, but the Black Dog had come breathing contagion, and she and the boy died in the filth of their cell.”

She tried to push herself away out of the hollow of his arms so that she could see his face, but he held her tightly to his chest. Her forehead rested against his neck and she could feel the working tendons and muscles of his throat constricting, his jaw hinging wordlessly up and down, up and down, as though testing the air for further grief. She reached up and felt the slick of tears in the hollow of his cheek. Placing the flat of her palm over one eye, she gently stroked with her fingers the place where the scar on his brow lay, and waited for him to speak.

“I broke the back of the jailer who had locked my family away, and spent a month in Newgate Prison. From my cell, I heard the outcry of men and women, confined and tortured, attesting to the thing Cromwell had become: a man of treachery who schemed to claim kingship in all but name.

“The Protector himself paid for my release, but I took off the red coat of my rank then and put it in a wooden chest. The Irish dirk, the wooden stake that committed me to being an executioner, and even a parchment note written in Cromwell’s own hand were all put away from the prying eyes of men. I took up shop on Fetter Lane as an ironsmith and never again saw the living Cromwell.”

He pulled away, encircling her face with his two hands, tracing with his thumbs the swollen lids beneath her eyes. She met his gaze reluctantly, thinking of the time she had plundered the great oaken chest. But she now had a history for everything inside it: the faded red coat, the curious dirk, and the rolled parchment, within which the little wooden stake had been wrapped. She shivered, suddenly cold.

He said, “I yet think on my son as he could have been, were he to have lived. He was tall for a boy and had his mother’s love for music. But he is gone from me forever, and though I grieve for him, I cannot wish myself to be in that place where he is. Not yet, not yet.” He clasped the back of her neck and brought his forehead to rest against hers. “Children may die, Martha, as will we all. No one knows when that end-time may be. But for this day, we live. So bide with me. Bide with me and take from me what you can, as I will from you. And however long it is that we walk this earth, we can stand for one another and leave off grieving until one of us is gone. I’ll not ask you to be mine, for you were mine at the moment my eyes opened to you, fuming and roaring into the mouth of a wolf. I will never seek to blunt the fury in you, never, and will honor your will as my own. What say you? Can you be a soldier’s wife?”

She looked at him wonderingly and at length, remembering other women’s acquiescence to an awkward suitor’s prologue to marriage: girlish smiles and laughter following some artless boy’s long-limbed shuffling and shy proposals. In all her imaginings of a sober and practical union, the breeding of children, and the laboring drudgery of a woman’s sphere, she had never dared hope for the promise of this; that a man would take her knowingly for all her mannish, off-putting certitudes and canny will, her prickly refusals to adhere to womanly scrapings, her ferocious and ill-tempered nature. But how could it be other? To be a soldier’s wife would suit her well.

She kissed him in answer, pressing her body for a while into his, and, after a time, he gathered her up and led her home.

IT WAS THREE days afterwards that Patience found the red diary.

Martha had been finishing the hem of her cloak made from the English woolen for which she had traded the piglets at market, the blue-green cloth that Thomas had said was the color of the Irish Sea before a storm. She gathered it into folds around her neck, placing Thomas’s antler clasp first at one shoulder, and then the other, before moving to the small bedroom window to better see her work. It had stormed earlier in the day, but the rain had slackened and turned to a rolling fog, settling into dells like ponds of lambs’ wool. She caught herself humming a snatch of song before remembering the words: The song of winter becomes like sleep and drowns the air with a gentle roar; and limbs like fingers grasp the fruit, into which time doth pour.

The tune was mournful—it made her think of the inevitability, the nearness, of death—but she stopped her humming, guilty that Patience might have overheard her. Patience had barely spoken to her since Will, placed in a small coffin hastily provided by a neighboring carpenter, was laid into the ground. Martha had spent most of her time while indoors confined to her room, sewing or furtively writing in the diary, at times overcome with tears for the boy. Blessedly, no one else in the family had become ill, and John would soon be sent to bring back Joanna.

Earlier, she had heard the unmistakable sounds of an argument between Patience and Daniel coming from the common room. There were suppressed, passionate exchanges punctuated by the sounds of her cousin’s angry weeping, and Martha had waited until silence had returned, making her think that Daniel had led her cousin into their bedroom. Placing the cloak aside on the bed, she walked into the common room to build up the fire for the noon meal. She was startled to see Patience standing behind a chair, her fingers tightly gripping the ladder back, and in the chair in front of her sat Daniel, holding in his hands a red leather-bound book.

There was a moment of confusion when Martha simply stared, wondering that there should be a twin to her own singular journal. But Daniel’s face was stricken with something beyond grief. A crimped mask of fear had compressed his lips into two white slashes, and he asked, “Is this your doing?”

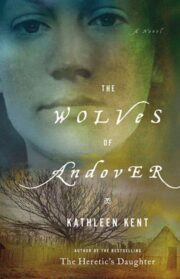

"The Wolves of Andover" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Wolves of Andover". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Wolves of Andover" друзьям в соцсетях.