'Someone shall get you whatever you need,' he said. 'They can get them immediately. It is bad for the baby if the mother does not eat. You shall have whatever you want.'

Alys shook her head. 'I need some powdered bark from an elm tree,' she said. 'It's a special tree I know. I could not direct anyone to it; it grows in a copse by the river at the foot of the moor. There must be a dozen elm trees there. Only I know which one I use.'

'Do you wish to go out there?' the old lord asked. ‘I would send you in a litter. It is not safe for you to ride.'

'I would do well on a mule,' Alys said. 'I would not fall, and I would not do more than a walk. No harm could come to me or the child. And I do indeed need the powders.'

'A couple of the men-at-arms shall go with you,' Lord Hugh decided. 'And your new maid. David said he has brought you a bonny wench who was anxious to serve you. You could go tomorrow morning and be back by dinner.'

'Yes,' Alys said. 'Or we could take our dinner with us. It should be fine again tomorrow, and then I will not have to hurry. I do not want to have to trot or canter.'

'No, no,' the old lord said hastily. 'Take all day if you wish, Alys, as long as you are safe. Stay out of the bright sunlight and take care that you do not overtire yourself.'

'Very well,' Alys said agreeably. 'As you desire, my lord.'

Hugo did not come to the ladies' gallery nor to Alys' room that night. Mary, the new maid, slept in Alys' room on a little truckle bed which rolled out on wooden wheels from underneath the big bed. Alys lay in the darkness listening to Mary's steady breathing with rising irritation. At midnight she shook her awake and told her to go and bed down in the gallery. 'I cannot sleep with you in the room.'

'Very well, my lady,' the girl said. Her fair hair was tousled into ringlets, her cheeks rosy. She blinked owlishly at Alys, still half asleep. Her shift, open at the neck, showed the inviting curves of her breasts.

'Go,' Alys said irritably. 'I shall not sleep until I am alone.'

'I'm very sorry, my lady,' Mary said. She went as quietly from the room as she could, picking her way in the darkness. She closed Alys' door with silent care and then clattered into a stool in the gallery. Then there was silence. Alys rolled over and slept for the rest of the night.

In the morning she ordered Mary to bring her ale and bread and cheese, and ate it sitting up alone in the great bed. She told Mary to pour hot water into a ewer and bring it to her, and to warm a bath sheet before the fire for Alys to dry herself. Mary went to the chest of gowns.

'The brown gown,' Alys said. 'And the black stomacher and the black gable hood.'

When she was dressed she looked at herself in the hand-mirror. The stomacher flattened her belly and her breasts into one smooth board. Hildebrande would not see the curve of her pregnancy. The old-fashioned gable hood rested low on her forehead at the front and covered her hair completely at the back. The brown gown was a rich, warm russet, elegantly cut – but as unlike the cherry-red gown of Meg the whore as any Alys owned.

'Can you ride?' she asked Mary as they came down the stairs.

Mary nodded. 'My father once owned a little farm,' she said. 'He kept many horses. He bred them for the gentry.'

'Does he have it no longer?' Alys asked, leading the way through the inner gate, across the drawbridge, and across the other manse to the stables.

Mary shook her head. 'They were lands belonging to the abbey,' she said. 'When the abbey was wrecked the land was bought from the King by my Lord Hugh. The rents were too high for us, we had to leave.'

'What does your father do now?' Alys asked idly. Mary shook her head. 'The loss of his farm was like death to him,' she said. 'He does a few jobs – shearing in summer, haymaking. Digging in winter. Most of the time he is idle. They live very poor.'

'You can ride my pony,' Alys said. 'I'll take a mule. We can swap when we are out of sight of the castle. Lord Hugh worries too much about my safety.'

Mary nodded, and the stable-lad led the horses out. She mounted easily, shaking out the skirts of her grey gown with as much grace as if she were noble enough to wear colours. The lad whistled at her and Mary tossed back her blonde ringlets and smiled at him. Alys was lifted to the mule's back and kicked the animal into a walk.

Two men-at-arms joined them as they passed through the gateway into Castleton. One walked before them, one behind.

They went briskly over the bridge and up the hill. The sun was bright on the straight, pale road before them, it would be another hot day. Alys, feeling the weight of the gable hood and the heat of the cloth on her neck, looked enviously at Mary who sat easily and confidently on the mare, looking all around her at the rye turning yellow in the fields, and the pale green of the wheat.

'Harvest soon,' she said pleasantly. 'It's been a good year for grains. And it'll be a good autumn for fruit, my father says.'

'Pull up, ' Alys said abruptly. 'I'll ride my own horse now.'

Mary stopped and the soldiers helped the two women exchange mounts. They rode on in silence as the road climbed higher and higher and the fields gave way to rough pasture land – good for nothing except sheep -and then they were out in the thick heather-purple haze of the open moorland. The hills around them stretched forever into the distance, the sky above them arched like a massive bowl of blue. Larks spiralled upwards, singing and singing. Over a cliff face on the right-hand side, broad-winged buzzards hung effortlessly on the warm air. Higher still above them was a circling dot in the sky, a golden eagle.

The river was gone, hidden underground as if it had secrets too dark for the sunshine. The hard, white limestone river bed threw back the light of the sun in a stony glare. Alys was glad when they rode into the green shadow of the coppice.

'You can sit here and eat your dinners,' she said to the three of them. 'I am going deeper into the wood for the bark of a special tree. Wait here for me. I may be some time, I will have to find the best tree and cut the bark. Don't come searching for me, I shall be perfectly safe and I don't want to be disturbed.'

The two soldiers hesitated. 'Lord Hugh said to keep you safe,' one of them objected.

Alys smiled at him. 'What could harm me here?' she asked. 'There is no one on the road and no one in this wood. I was brought up here, I know these parts better than anyone. I shall be safe. I shall not be far. I shall hardly go out of earshot. Rest here until I return.'

She rode down the slope, her mare stepping carefully over the roots in the path, and drew rein when she was out of sight. She waited for long moments. No one was following. Alys turned the horse's head upstream and kicked her into a trot and then into a canter along the grassy bank of the river and up to Morach's cottage. Mother Hildebrande was sitting in the doorway, her tired old face turned to the sun as if she were soaking in the warmth. She opened her eyes when she heard the noise of the pony and stood up, hauling herself up the frame of the door.

Alys dismounted, tied the pony to the hawthorn bush, and stepped over the sheep stile.

'Mother,' she said. She glanced around swiftly. The open moorland all around the cottage was bare and empty. Alys knelt on the threshold and Mother Hildebrande rested her trembly hand on Alys' head and blessed her.

'You are come at last, daughter,' Mother Hildebrande said.

Alys stood up. There was determination in the old woman's eyes.

‘I cannot stay,' Alys said gently. 'Not yet. That is what I came to tell you.'

The old woman eased herself down on the stool at the doorstep. Alys sat at her feet. Mother Hildebrande said nothing. She waited.

'I am not unwilling,' Alys said persuasively. 'But Lady Catherine is ill, near to death, and no one there can care for her. She has miscarried her child and is scouring with a dreadful white fluid which they say is a curse upon her and upon Lord Hugh's house for the sacrilege of destroying our nunnery. A holy woman is needed there. She needs me to protect her from fear. No one knows what to do. She is mortally afraid and for no fault of her own. I cannot believe that our merciful Lord would want me to abandon her. And anyway, they would not let me go. Even now I am only released from the castle to fetch some herbs and some elm bark for her.' Mother Hildebrande said nothing. She sat very still, watching Alys' clear profile as Alys sat at her feet, leaned back against her knees as she always used to sit -and lied.

'The old lord is tender with my beliefs,' Alys said urgently. 'He does not care which faith he follows. But his son is a Protestant, an unbeliever. It was he who wrecked our abbey, and now he is turning his attention to every religious house for miles around. His father is Sheriff of the County but it is Hugo who rides out and does the King's sacrilege. He believes in nothing, he trusts nothing. He hates the true faith and he captures and imprisons believers. If he knew you were here – the Mother of an Order he had wrecked – he would hunt you down and hurt you until you were driven to deny your faith.'

Mother Hildebrande looked at her steadily. 'I do not fear him,' she said gently. 'I fear nothing.'

'But what good does it do?' Alys demanded passionately. 'What good does it do to risk danger, when with a little care and caution and delay you could get away to safety? Isn't that the Lord's work? To get to safety so that you can live according to His laws again?'

Mother Hildebrande shook her head. 'No, Sister Ann,' she said. 'Saving your own skin is not the Lord's work. You are speaking with the persuasive voice of the world. You are speaking of clever practice and winning by deceit. The way we are promised is not that way. The Lord's work is to proclaim Him in words and to demonstrate Him in our lives. I have never been skilled with words, I have never been a clever woman; but I can be a wise woman. I can be a woman who can show by her life a lesson which a more learned woman would write in a book. I cannot argue truths – but I can demonstrate them. I can live my life, and die my death, as if there were some things which matter more than clinging to goods and staving off death.' 'It is not wise to die!' Alys exclaimed. Mother Hildebrande laughed gently, the dry old skin of her face wrinkling easily with her smile. 'Then all men are fools!' she said softly. 'Of course it is wise to die, Alys. Everyone will die, all that we can choose is whether we die in faith. Whether your dangerous young lord comes for me today, or whether I die surrounded by my friends in a comfortable bed, does not matter to my immortal soul, just to my frightened body. Wherever and whenever I die, I want to die in my faith and my death will show that the most important thing in my life was keeping my faith.' 'But I want to live!' Alys said stubbornly. The old woman smiled. 'Oh, so do I!' she said, and even Alys could hear the longing in her voice. 'But not at any price, my daughter. Both of us took that decision when we took our vows. Those vows are harder to keep now than it seemed when you were a little girl and the abbey was the finest home you could have hoped for. But the vows are still binding, and those who have the wisdom to hold to them will have the joy of knowing that they are one with God and with His Holy Mother.' They were both silent.

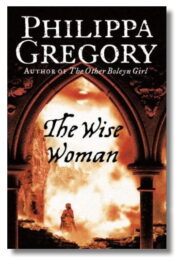

"The Wise Woman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Wise Woman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Wise Woman" друзьям в соцсетях.