They had a scythe ready sharpened for Hugo, and the bailiff who had ordered and overseen the haymaking was * dressed in his best, his wife beside him, ready to hand the scythe to the young lord. Hugo jumped down from the saddle and threw his reins to a page-boy. Then he turned and helped Alys down. Hand in hand they went towards the farmer and his wife; Alys kicked at the long piles of cut grass, sniffing at the sweet, heady smell of the meadow flowers and the new-mown hay. Her new green gown rustled pleasantly over the stubble. Alys raised her head to the sunshine and strode out as if she owned the field.

'Samuel Norton!' Hugo said pleasantly as they drew close. The bailiff pulled off his hat and bowed low. His wife dropped down in a weighty curtsey. When she came up her face was white, she did not look at Alys.

'A good crop of hay!' Hugo said pleasantly. 'A grand hay crop this year. You will keep my horses in good heart for many winter nights, Norton!'

The man mumbled something. Alys stepped forward to hear what he was saying. As she did so the woman flinched backwards in an involuntary, unstoppable movement.

Alys checked herself. 'What's the matter?' she asked the woman directly.

The farmer flushed and blustered. 'My wife's not well,' he said. 'She would insist on coming. She wanted to see you, my lord, and the Lady Cath…' he broke off. 'She's not well,' he said feebly.

The woman curtsied again and started to step backwards, her Sunday-best gown brushing the cut hay, picking up seed heads.

'What's this?' Hugo asked carelessly. 'You ill, Good-wife Norton?'

The woman was white-faced, she opened her mouth to reply but she could not speak. She looked from her husband to Hugo. She never once glanced at Alys.

'Forgive her,' Farmer Norton said hurriedly. 'She's ill you know, women's time, women's fancies. All madness in the blood. You know how women are, my lord. And she wanted to see the Lady Catherine. We did not expect…'

Hugo's bright cheerfulness was dimming rapidly. 'Did not expect what?' he demanded ominously.

'Nothing, nothing, my lord,' Farmer Norton said anxiously. 'We mean no offence. My wife has a present for the Lady Catherine – some lucky charm or women's nonsense. She hoped to see her, to give it to her. Nothing more.' ‘I will give it to her,' Alys said, her voice very clear.

She stepped forward, the folds of the green silk shimmering around her. She held out her hand. 'Give me your gift to Lady Catherine and I will give it to her. I am her closest friend.'

Goodwife Norton clenched the little purse she wore at her waist. 'No!' she said with sudden energy. ‘I’ll bring it up to the castle myself. It's a relic, a girdle, blessed by St Margaret to aid a woman in childbirth, and a prayer to St Felicitas to ensure the child is male. It has stood me in good stead, half a dozen times. Lady Catherine shall have it. You shall have it, my Lord Hugo, for your son! I will bring it up to the castle and I will put it in her hands.'

'Give it to me!' Alys said, her anger rising. 'I shall give it to her with your compliments.'

She reached out towards the woman and Goodwife Norton flinched backwards as if from a dangerous animal.

From the waiting men and women all around the field there was a hiss, like a cat as it senses danger.

'Not into your hands!' The woman suddenly found her voice, sharp and shrill. 'Into any hands in the world but yours! It's a holy relic saved from the nunnery. The holy women kept it safe for the good of wives, married women! For women carrying their husbands' children in matrimony. For childbirth in the marriage bed. It's not for the likes of you!'

'How dare you sneer at me!' Alys said breathlessly. She reached again for the little bag in Goodwife Norton's hand.

Now she could see it more clearly. It was a little velvet purse, rubbed smooth in the middle by the kisses of women praying for an easy childbirth. She remembered it from the nunnery. It had been kept in a golden casket near the altar and when a woman big with child came into the chapel she could whisper to one of the nuns that she wanted to kiss it. No one, however poor, however needy, was refused. Alys found she was staring at the gold stitching on the purse. She remembered the Mother Abbess herself had stitched it. My mother,' Alys thought. The sudden sharp pain made her angry.

'You're nothing better than a thief yourself!' Alys said. 'That belongs in the nunnery, not hawked around a hayfield. Give it to me!'

'Witch!' Goodwife Norton spat. She leaped back so Alys could not reach her and then she said the word again – 'Witch!' She spoke under her breath but it was as loud and clear as if she had screamed it. The whole haymaking gang froze into silence.

Alys felt the world grow still around her as if she were a painted piece of glass on a fragile leaded window. Nothing would move, nothing would make a sound. Goodwife Norton should not have said that word and she should not have heard it. The haymakers, the village people, the townspeople, and the people from the castle should not have that word in their minds. It should not have been said. Alys did not know what to say or do to take the sudden danger out of the innocent morning. Hugo stepped forward. 'Norton?' he prompted softly. The bailiff said briskly, 'I beg your pardon, Lord,' and seized his wife by the elbow and marched her rapidly across the field. At the first woman he stopped and thrust his wife towards her with a rattle of low-voiced orders. The two of them bent their heads and scuttled from the field like rats fearing the scythe. Farmer Norton strode back, his red face furious. 'Damned scolds,' he said, as one man to another. Hugo was unsmiling. 'You should have a care, Farmer Norton,' he said. 'A wife with a tongue as loose as that will find herself charged with slander. These are serious accusations to fling around. A noble lady should not have to listen to such.'

The man said nothing. He looked stubborn.

'I do not think you have been presented to Mistress Alys,' Hugo said smoothly. 'She is a dear friend of my wife, she is my father's clerk. She is my chosen companion today. I will lead the dancing with her.'

Norton flushed a deep brick-red of shame. Alys glared at him, her eyes blazing blue with her challenge. He dropped his head in a deep bow.

Alys waited. Then she held out her hand.

He took it reluctantly and kissed the air just above her skin. She felt his hard, callused hand tremble underneath her touch.

He straightened up. 'We've met before,' he said bravely. 'I knew your mother, the Widow Morach. I knew you when you were a child, playing in the dirt of the lane.'

Alys gave him a cold, level stare. 'Then you know she was not my mother,' Alys said. 'My real mother was a lady. She died in a fire. Morach was a wet nurse to me, a foster-mother. Now she is dead and I am back where I belong. In the castle.'

She turned to Hugo. 'I shall sit with Lord Hugh,' she said pleasantly, 'in the shade, while you cut your swathe of hay. Bring me a handful of hay and flowers!'

She spoke clearly enough for all to hear her ordering the young lord as a mistress orders her lover; and then she turned on her heel and walked across the soft stubble of the hayfield to where the old lord sat in the shade. It was a long, long walk with the eyes of the haymakers and the castle people on her every step. The new gown swept the hay around her. Green, the colour of spring, of growth… and of witchcraft. Alys, wishing that she had worn a gown of another colour, kept her head up and smiled around at everyone. Wherever her gaze fell people turned away their heads, shuffled their feet. She walked across the field like a new, dangerous dog walking through a flock of sheep. People shifted like wary old yows to keep their distance.

But they whispered. Alys could hear the soft susurration of dislike, as quiet as the wind shifting in the uncut hay. 'Where is Lady Catherine?' someone called from the back, louder than any other. 'Where is Hugo's wife? We want the lady to come from the castle for haymaking, not the castle slut!'

Alys kept her head high, her eyes steadily flicking around the watching field, the smile unwavering on her mouth. Never could she catch someone speaking. Always their faces were blank and fearful. There was no one she could name as her slanderer. However quickly her gaze went from one stubborn face to another the whisper preceded her. Underneath her arms she could feel the gown growing damp. She nearly stumbled as she reached the bower like a criminal running to sanctuary. Then she checked. There was no chair for her. David and the old lord were sitting down.

'I will trouble you for your chair, David,' she said bluntly. 'It was hot in the sunshine and I wish to sit.'

For a moment, for half a moment only, it seemed as if he would refuse her.

'Let the wench sit,' the old lord said irritably. 'She's carrying my grandson in her belly.'

David rose reluctantly and went to stand behind the old lord's chair.

'What was all that about?' the old lord asked.

Alys sat still, her hands quietly in her lap, her face composed. 'Country gossip,' she said. 'They envy me, those who knew Morach and the nasty little cottage. They cannot understand how I should move from there to here. They make up fancies of witchcraft and then they frighten nobody but themselves. That fat old shrew, Goodwife Norton, has taken it into her thick head that I have bewitched the young lord and supplanted Catherine. She sought to insult me.'

The old lord nodded. Out in the field Hugo had stripped off his thick, costly jacket. A pretty girl with brilliant golden hair had stepped forward and was holding it for him. As they watched she held it to her cheek. They heard Hugo's flattered laugh. Farmer Norton handed him a scythe. Hugo rolled up his white linen sleeves, spat on both palms, and took it in a firm grip. There was a ragged cheer from the crowd. Hugo was popular this year, with high wages for the labourers at his new house and his wife pregnant.

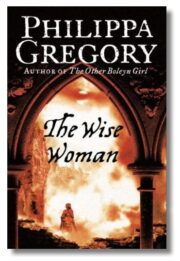

"The Wise Woman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Wise Woman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Wise Woman" друзьям в соцсетях.