"Tisn't natural, for a woman to have such learning,' Mistress Allingham said roundly. 'No wonder she looks so thin and plain. She's working all the time with her mind and not growing plump and bonny like a girl should.' 'Plain?' Alys repeated, shocked. Eliza nodded, mischievously. 'Why did you think you were so high in my lady's favour? Because Hugo never looks your way no more! You're all thin and bony, Alys, and white as frost. He bundles up with Catherine and folds himself around her fat belly and thanks God for a bit of warm flesh in these cold nights.'

'She'll bloom in summer,' Morach said again. 'Leave the girl alone. The long cold dark days of this spring would weary anyone.'

The talk moved on at Morach's bidding but later that evening after supper, Alys slipped into Lady Catherine's room while the rest of them were drinking mead around the fire in the gallery. She carried a candle with her and set it down before the glass to see her face. It was a large handsome mirror made of silvered glass and the reflection it gave was always kindly, forgiving. Alys set down the candle and looked at herself. She was thinner. The gown of Meg the whore was wider than ever, the girdle spanned her waist and hung down low and the stomacher, laced as tight as it could go, flattened her slight breasts but was loose over her belly. She slipped her shawl back. Her shoulders were as scrawny as an old woman's, her collar bones like the bones of a little sparrow. She stepped a little closer to see her face. There were dark shadows beneath her eyes and lines of strain around her mouth. She had lost her childish roundness and her cheeks were thin and pale. Her blue eyes looked enormous, waif-like. She radiated coldness and loneliness and need.

Alys made a sour face at the mirror. 'I'll not get him back looking like this,' she said under her breath. She stepped a little closer. The shadows under her eyes were as dark as bruises. 'I'll not get him back at all,' she said softly. 'He could have loved me when I was straight off the moor, taught by my Mother Abbess, and skilful like Morach. He could have loved me then and been true to me then, and none of this misery would ever have happened. Now I've set my hand to magic and he's been witched, and she's been witched, and something is eating me away from the inside, like some great greedy worm, so all my strength drains from me and all I have left is my longing for him.'

The face in the mirror was haggard. Alys put her hand up and felt the tears on her cheek. 'And my magic,' she said softly. 'Longing and magic enough to hurt and wound. That's all I have left me. No magic to summon a man to love me.'

She sighed and the candleflame bobbed at her breath and spat a trail of smoke. Alys watched it wind towards the bright-painted timbered ceiling. 'I dipped very deep to be rid of him,' she said softly to herself. 'I used all the power I had to turn his eyes from me and his mind from me. I'll have to go that deep again to get him back.'

The candleflame quivered, as if in assent. Alys leaned forward. 'Shall I do it?' she asked the little yellow flame.

It dipped again. Alys smiled, and her face lit up with her youth and her joy again.

'Flame-talking!' she said softly. 'A flame as a counsellor!'

The room was very still; in the gallery she could hear someone take up a lute and strike a few chords, trying the sound. The chords hung on the air as if Alys was holding back time itself while she made her decision.

'It's more deep magic,' she said thoughtfully. 'Deeper than I know. Deeper than Morach knows.' The candleflame flickered attentively. 'I'll do it!' Alys said suddenly. 'Will it win me Hugo?' The flame leaped and a tiny spark shot out from a fault in the wick. Alys gave a start of surprise and then clapped her hands over her mouth to hold in a ripple of laughter. 'I win Hugo!' she said delightedly. 'I get what I want!' She snatched up the candlestick and turned to go from the room. As she walked the flame billowed out like a streamer, lighting the walls and Hugo and Catherine's big curtained bed so its shadow leaped up and jumped like a huge stalking animal. Alys opened the door to the gallery and stepped into the brightly lit room and the music. In its stick, unnoticed, the candleflame winked and went out.

The women were gathered around the fireside. Catherine, round and warm, was leaning back in her chair, her eyes closed, listening to Eliza plucking at the lute. Alys passed like a pale cold ghost through the room, carrying a darkened candlestick, and slipped into her bedroom.

She closed the door behind her but still Eliza's careless off-key warble came through. She leaned her back against the door as if she would blockade the room from them all. Then she shrugged, as a gambler does when he has nothing more to lose, crossed to the garderobe and rolled her sleeves up. Wrinkling her nose at the smell, she reached down the gap in the wall to feel for the string and the bag of the candle dolls. The bag was stuck to the castle wall, caked with muck. Alys' fingers scrabbled, trying to get a grip. She got hold of one corner and tore the purse away from the wall and up into the room.

'Faugh!' she said under her breath. She carried it over to the stone hearth and pulled at the neck of the purse. The stiff string was stubborn but snapped at last and the candle dolls spilled out on to the hearth.

Alys had forgotten how ugly they were. The little doll of Catherine with her legs spread wide and her grotesque fat belly, the old lord with his beaky, hungry face, and Hugo – beloved Hugo – with his eyelids wiped blind, his ears rubbed away, his mouth a smear and his fingers clumsy stumps. Alys shivered and tossed the purse on the fire; it sizzled and a rank smell of midden filled the room. Alys pulled a stool closer, put the three dolls on her lap and gazed at them.

Very quietly the door behind her opened and Morach came in, soft-footed.

'Oh,' she said gently. 'I felt your magic even while I was gossiping about London news out there. But I did not think you would have turned to the dolls again.'

Alys looked at her, blank-faced. She did not even try to hide the horrors she had made of Morach's little statues.

Taking your power again, are you?' Morach questioned. Alys nodded, saying nothing.

'You heard what they said of your looks at dinner,' Morach said, half to herself. She hunkered down on the hearth-rug beside Alys. 'You heard what they said about you, that Hugo loves Catherine, that Catherine fears you no more because you have lost your looks.'

Alys remained silent, the little dolls side-by-side on her lap. Morach took the poker and stirred the fire so the log fell backwards and she could see a deep red cave of embers. 'Bitter that was for you,' she said, looking deep into the fire. 'Sour and bitter to know that your looks are going and you have had so little joy from them.'

Alys said nothing. The dolls in her lap gleamed wetly in the glow from the fire as if they were warming back to life after their long cold vigil hung outside the castle wall.

'And you've taken Hugo's desertion badly,' Morach said softly. She did not look at Alys, she looked into the heart of the fire as if she could see more there. 'You saw him dive into the river and pull Catherine out. You saw him wrap her warm and bring her back as fast as his horse would go. You saw him hold her and kiss her, and now you see him, unbidden, at her side every day and in her bed every night. And how she grows and beams and thrives on his love! While you – poor sour little Alys – you are like a snowdrop in some shady corner of the wood. You grow and flower in coldness and silence, and then you die.'

The smell from the burning purse eddied around the two of them like smoke from the depths of hell. 'So you want your power,' Morach said. 'You want to make the dolls yours again, you want to make them dance to your bidding.'

'Fashion him again,' Alys said suddenly, holding out the mutilated doll of Hugo to Morach. 'Make him whole again. I commanded him not to see me, not to hear me, not to touch me. I commanded him to lie with Catherine and get her with child. Lift my command off him. Make him whole again and passionate for me. Make him back to what he was at Christmas when he carried me from the feast, to lie with me whether I would or no. Make him how he was when he faced her down and swore false oaths to keep me safe. Make him what he was when he sat by the fire – in that very room where she sits now – and told me that she disgusted him, that he lay with her only to keep me safe, and that his body and soul craved to be with me. Make him that again, Morach! Make him new again!'

Morach sat very still, then she slowly, almost sadly, shook her head. 'It cannot be done,' she said gently. 'There is no magic that can do it. You would have to turn back time itself, turn back the seasons to Christmas. All that has happened here since then has happened, Alys. It cannot be undone.'

'Some of it can be undone,' Alys insisted, her face small and pinched, her voice venomous. 'The child can be undone, Morach. The child can be undone in its mother's belly. The child can be stillborn. Catherine can die. Then even if he does not love me – at least he does not love her. And when she is gone, and the child is gone, he will turn back to me.'

Morach shook her head. 'I won't do it,' she said softly. 'Not even for you, Alys, my child, my poor child.' She shook her head again. 'I've aborted babes and I've given women miscarriages,' she said. 'I've blighted cattle, oh yes, and men's lives. But they were always people who were strangers to me, or those I had reason to hate. Or the babies were unwanted and the women desperate to be rid of them. I couldn't blight the child of a woman I live with, whose bread I eat. I couldn't do it, Alys.'

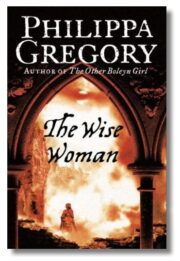

"The Wise Woman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Wise Woman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Wise Woman" друзьям в соцсетях.