Alys shook her head, thinking. 'I am nowhere alone!' she said impatiently. 'I am with someone all day and every day. Even when I am in the herb garden there is always someone near by, a servant or a gardener or one of the scullions.'

Morach nodded. 'Hide them somewhere foul,' she advised. 'In the castle midden or under a close stool. Somewhere that not even a child would pry.'

'Out of the garderobe!' Alys exclaimed. She pointed to the corner of the room where a round hole had been cut into the wall and covered with a wooden lid. 'You take your ease there,' she said. 'And the shit falls down into the moat. No one would search there. I can hang them on a piece of cord from underneath the seat.'

Morach eyed the corner seat. 'That'll do,' she said. 'In time they'll get marked and foul. No one will see them. And whatever power your spell has laid on them I cannot see them hexing your Lord Hugo to hang outside the castle wall while you shit on his head.'

Alys gave a sudden giggle and her whole face lightened. For a moment she looked like the girl who had been the favourite of the whole abbey. 'I'm glad you're here,' she said. 'Now I'll call for hot water for you. You'll have to have a bath.'

Thirteen

Morach was unruly about bathing, ashamed of being naked before Alys, certain that water would make her ill.

'You smell,' Alys said frankly. 'You smell disgusting, Morach. Lady Catherine will never have you near her smelling like this. You're as bad as a dungheap in August.' 'Then she can send me back to my cottage,' Morach grumbled while the servants came up the stairs with the big bath and the cans of hot water. 'I didn't ask for some lout of a man to come riding all over my garden and snatch me off to come to help a woman in childbirth for a baby that's only just conceived.'

'Oh, hush,' Alys said impatiently. 'Wash yourself, Morach. All over. And your hair too.'

She left Morach with the steaming bath and when she returned, with a gown from the chest, Morach was wrapped in the counterpane from the bed, as near to the fire as she could get.

'Folks die of wetting,' she said dourly. 'They die of dirt as well,' Alys retorted. 'Put this on.' She had chosen a simple green gown for Morach, a working woman's gown with no stomacher and no overskirt; and when she was dressed and the girdle tied, and a foot of material stitched up into a thick hem, she looked well.

'How old are you, Morach?' Alys asked curiously. She seemed to have stayed the same age for all of Alys' life. Forever bent-backed, forever greying, forever lined, forever dirty.

'Old enough,' Morach said unhelpfully. 'I'm not wearing that damned cap.'

'I'll just comb your hair then,' Alys said. Morach fended her off. 'Stop it, Alys,' she said. 'I may be far from my hearthside, but I don't change. I don't want you touching me, I don't want to touch you. I am a hedgehog, not a coney. Keep your hands off me and you won't get prickled.'

Alys recoiled. 'You've never wanted me touching you,' she said. 'Even when I was a little girl. Even when I was a baby I doubt you touched me more than you had to. I can't remember sitting on your knee. I can't remember you holding my hand. You're a cold woman, Morach, and a hard one. And you brought me up longing and longing for a little tenderness.'

'Well, you found it, didn't you?' Morach demanded, unrepentant. 'You found the mother you wanted, didn't you?'

'Yes,' Alys said, recognizing the truth of it. 'Yes, I did find her. And I thank God I found her before I had tumbled into Tom's arms for gratitude.'

Morach gleamed. 'And how did you repay love?' she asked. 'When you found your mother, when you found the woman to hold you and kiss you goodnight and tell you stories of the saints, and teach you to read and to write? What sort of a daughter were you, Alys?'

Alys turned a white face to Morach. 'Don't,' she said.

'Don't?' Morach asked, deliberately dense. 'Don't what? Don't say that all this love counted for so much that at the first sniff of smoke you were away like a scalded cat? Don't remind you that you left her to burn with all your sisters while you skipped home at an easy pace? Don't remind you that you're a Judas?

'I may be cold, but at least I'm honourable. I decided to feed you and house you and I kept my promise. And I did more than that – it suits you to forget it now. But I did dandle you and tell you stories. I kept you safe as I promised I would. I taught you all my skills, all my power. From your earliest days I let you watch everything, learn everything. There's always been a wise woman on the moor, and you were to be the wise woman after me.

'But you were too clever to be wise. You had to find your own destiny, and so you promised to love your mother and her God forever; but at the first hint of danger you ran like a deer. You ran from her, back to me; and then you ran from her God, back to magic again. You're a woman of no loyalty, Alys. It's whatever will serve a purpose for you.'

Alys had turned away and was looking out of the window where the sun was coming through the snow-clouds, hard and bright. Morach noted her hands on the stone window-sill, clenched until the knuckles showed white. 'I am not very old,' she said, her voice shaking. 'I am not yet seventeen. I would not run again. I have learned some things since the fire. I would not run now. I have learned.'

'Learned what?' Morach demanded. 'I have learned that it would have been better for me to have died with her than to live with her death on my conscience,' Alys said. She turned back to the room and Morach saw that her face was drenched in tears. 'I thought that as long as I survived, that was all that mattered,' she said. 'Now I know that the price I paid for my escape is high, too high. It would have been better for me to have died beside her.'

Morach nodded. 'Because you are now alone,' she said.

'Very, very alone,' Alys repeated. 'And still in danger,' Morach confirmed. 'Mortal danger, every day,' Alys said. 'And deeply enmeshed in sin,' Morach finished with satisfaction.

Alys nodded. 'I am beyond forgiveness,' she said. 'I can never confess. I can never do penance. I am beyond the pale of heaven.'

Morach chuckled. 'My daughter after all,' she said, as if Alys' despair was the stuff of rich comedy. 'My daughter in every detail.'

Alys thought for a moment and then nodded. The bowing of her head was an acceptance of defeat.

Morach nodded. 'You may be a wise woman yet,' she said slowly. 'You have to watch everything go. You have to see everything slip away from you, before you can be wise enough to do without.'

Alys shrugged sullenly. 'I have Hugo,' she said stubbornly. 'I have his promise. I am not a poor old witch on the moor just yet.'

Morach gleamed at her. 'Oh yes,' she said. 'I was forgetting that you have Hugo. What joy!'

Alys released the grip of her hands. 'It is a joy,' she said defiantly.

Morach grinned. 'Did I not say so?' she demanded. She laughed. 'So then! When do I see her? Catherine. When do I see her?'

'You call her Lady Catherine,' Alys warned. 'We can go and see her now, I suppose. She's sewing in the gallery. But watch what you say, Morach. Not one word of magic or she will have us both. She no longer fears me as a rival, but she would not resist the temptation to get rid of me, if you gave her the evidence to put me through another ordeal.'

Morach nodded, the old slyness back in her eyes above the green shawl. 'I don't forget,' she said. 'I'm not bought with a whore's gown. I'll keep my silence until I'm ready to speak.'

Alys nodded and opened the door. The women were sitting at the far end of the gallery with the yellow wintry sun shining through the arrow-slits on their work. They all turned and stared as Alys led Morach into the room.

'Anyway,' Morach said behind her hand, 'it wasn't me that used the magic dolls was it, Alys?'

Alys shot Morach one furious glance and walked forward. 'Lady Catherine,' she said. 'May I present to you my kinswoman, Morach.'

Lady Catherine looked up from her sewing. 'Ah, the cunning woman,' she said. 'Morach of Bowes Moor. I thank you for coming.' Morach nodded. 'No thanks are due to me,' she said. Lady Catherine smiled at the compliment. 'Because I didn't choose to come,' Morach said baldly. 'They rode up to my cottage and snatched me out of my garden. They said it was done on your orders. So am I free to go if I wish?'

Catherine was taken aback. 'I don't… ' she started. 'Well… But, Morach, most women would be glad to come to the castle and live with my ladies and eat well, and sleep in a bed.'

Morach gleamed under the thatch of grey hair. 'I'm not "most women", my lady,' she said with satisfaction. 'I am not like most women at all. So I thank you to tell me: am I free to come and go as I please?'

Alys drew breath to interrupt, but then hesitated. Morach could take what chances she wished, she had clearly decided to haggle with Lady Catherine. Alys chose to avoid the conflict. She left Morach standing alone in the centre of the room and went to sit beside Eliza and looked at her embroidery.

'Of course you are free,' Lady Catherine said. 'But I require your help. I have no mother or family near to advise me. Everyone tells me you are the best cunning woman in all the country for childbirth and cursing. Is that true?'

'Not the cursing,' Morach said briskly. 'That's just slander and poison-talk. I do no curses or spells. But I am a healer and I can deliver a baby quicker than most.'

'Will you deliver mine?' Lady Catherine asked. 'When he is born in October? Will you promise to deliver me a healthy son in October?'

Morach grinned. 'If you conceived a healthy son in January, I can deliver him in October,' she said. 'Otherwise… probably not.'

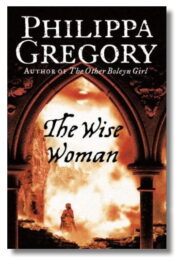

"The Wise Woman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Wise Woman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Wise Woman" друзьям в соцсетях.