'I felt very tender towards her,' Hugo said awkwardly. 'I've never felt like that with a woman before, not even a favourite whore. I felt as if I wanted her to sleep. I felt as if I wanted to guard her rest.'

The old lord barked a short laugh. 'That's not witchcraft – that is love,' he said briefly. 'I thought you'd never fall for it, Hugo. You're on a merry road now!'

For a moment the two men grinned at each other, warm with fellow-feeling.

'And for a little drab from the moor,' Hugo said wonderingly.

His father chuckled. 'You can never tell,' he said softly. 'And you'll fall hard, Hugo. I wager you do! She'll lead you a dance, that girl!'

'Never mind that!' Lady Catherine hissed. 'There is witchcraft here! What of her naming the year as 1538? What of her calling herself eighteen? How old is she now? Sixteen! And it's 1536! And what of your death? And what of me? She is in league with the devil, she is foretelling our ends – and in only two years unless she is stopped now!'

The old lord nodded. 'What d'you think?' he asked the priest.

The man's face was brooding. 'I know not what to think,' he said. 'It looks very bad. I should want to think and pray for guidance. God will send us a sign to protect us from these terrors within our walls.'

Lady Catherine leaned forward, her eyes glittering in the candlelight. 'Your own lord is threatened with death in a year's time and you know not what to think?' she asked. The priest stared back at her, unafraid. 'There is malice in the witness against her,' he said levelly. 'Maybe this wench dislikes her, you certainly have reason to hate her, my lady. If she is accursed then it will show in her speech and behaviour. I think we should see her and judge her on her behaviour when she is accused.'

'And let her enchant you all!' Catherine cried out. 'Be still, Madam,' the old lord rumbled. He nodded to Hugo. 'Call for Alys,' he said. 'We'd better have her here.'

The priest looked briefly at Catherine and seated himself at the table in the window. 'She will not enchant me,' he said briefly. 'I have ordered many witches to their deaths. I have watched many women take ordeals where strong men have turned aside sickened. I am merciless in the work of God, Lady Catherine. If she is on the side of the devil then she should surely fear me.'

Hugo strolled to the door, shouted for a servant again and ordered him to seek Alys. 'I believe in none of this,' he said conversationally. 'No magic, no witches, no spells. I believe in the world I can see and touch. All the rest is fairy-tales to frighten little girls.'

Father Stephen exchanged a glance with him. 'I know you like to think so, Hugo,' he said with affection. 'But you go dangerously close to heresy yourself if you deny the fallen angel and the battle against sin.' Hugo shrugged.

A silence fell for a few moments. Eliza edged nearer to the door.

'May I speak?' Catherine asked. The old lord nodded.

'I may have been hasty,' Catherine said, her voice level. The old lord bent a piercing look on her face. 'I was angry with my husband and angry with the wench. I may have been hasty in my accusations.' They waited. Hugo eyed her with open suspicion. 'As you say, my lord, Hugo is not necessarily bewitched. He could be in the grip of desire and tenderness.' Her voice did not shake with her jealousy, she held herself in iron control. 'I may feel affronted as his wife, but as the lady of the castle, as your ward, it does not concern me,' she said.

The old lord nodded. 'And so?' he asked drily. 'Only one thing in all of this is left to worry me,' she said.

The old lord waited.

'Your safety, Sire,' she said. 'If the girl wishes your death then she is well placed to harm you. And if she is a witch then we are all in danger. We have to know if she has black arts before we can judge whether or no to send her away. If she has powers then we cannot treat her like a naughty servant. She would do us all grave ill. We have to know. For our own safety.'

The priest nodded. The old lord glanced at him. 'What do you suggest, Lady Catherine?' he asked.

Catherine took a breath. She did not look at her husband. 'An ordeal,' she said. 'A test for her. To see if she is a witch or no.'

Hugo flinched involuntarily. 'I like not these ordeals,' he said. A glance from his father silenced him. 'Priest?' the old lord asked.

'I think so, my lord.' Father Stephen nodded. 'We have to know if her healing gifts are godly or not. And Lady Catherine is right to think that she can neither be sent away nor kept here while we are all in ignorance. Perhaps a gentle ordeal? Eating sanctified bread?'

A look of disappointment crossed Catherine's face, swiftly hidden.

'Did you hope to swim her, Catherine?' the young lord asked maliciously. 'Or set her in a burning haystack?'

'None of that! None of that!' the old lord said impatiently. 'She may well be a good girl and an honest servant with naught against her but your desires, Hugo, and her own special gifts. We'll do what the priest says. She'll take sanctified bread on oath and if it chokes her then we'll know what to do.'

Eliza's eyes were as round as saucers. 'Shall I go?' she asked.

'Stay!' the old lord said irritably. 'Where is the wench?'

Nine

After Alys had flung herself out of the ladies' gallery she ran as far as the outside gate before she hesitated. The air was icy and dry, as if it might snow at any moment. The town was closed and silent. Morach's cottage was half a day's walk away. Mother Hildebrande was gone forever. She could feel the absence of the abbey and the loss of her mother in the arid air, in the low soughing of the winter wind around the castle walls. There was nowhere for her to go.

She turned back at the castle gate and walked slowly across the outer manse. A few thin hens pecked at the cold earth. A fat sow. bulging with piglets, grunted in the sty. Alys shivered as the sun dipped down behind the high round tower. She walked across the second drawbridge, into the inner wall of the castle. Mother Hildebrande was dead, the abbey was in ruins. There was nowhere for her to go but back to the gallery to the spite and triumph of the women.

Her head was still hammering from the wine and from the sudden flood of her anger. She walked slowly, past the herb-beds to the well at the centre of the little garden. She wound up the bucket and drank the icy brackish water, tasted the foulness of it slick in the back of her throat. Then she walked on, past the great hall to the bakehouse, a little building round like a beehive set down between the brooding blackness of the prison tower and the castle physic garden. Alys pushed open the little door and peered curiously inside. It was warm and quiet. The two great rounded ovens held their heat like a brickyard. The floor, the tables, the shelves, even the brass tins on their hooks, were covered with a thin white film of flour. The bakers had deserted it after their morning's work – baking the bread for breakfast, dinner and supper in one long sweating shift. They had gone into town to find an alehouse, or into the great hall of the castle to gamble or doze. Alys went quietly inside and shut the door behind her. The room smelled sweetly of new-baked bread. Alys sank to her knees in the white dust at the hearth and found that tears were running down her face. For a moment she was back in the abbey kitchens watching the lay sisters bake and brew. For a moment she remembered the sweet white bread, milled from their own flour, baked in their own ovens, the hot warming taste of fresh-baked rolls for breakfast after prime in the early morning.

Alys shook her head, took up the bulky hem of her navy gown and rubbed her eyes. Then she sat back on her heels and stared into the warm heart of the bakehouse fire for long minutes.

'Fire,' she said thoughtfully, looking to the hearth. She rose up and lifted down two small tins from the wall. One she scooped full of water from the barrel by the table. She placed it before the fire. 'Water,' she said softly.

She took a handful of cold ash, fallen soot and brick dust from the back of the chimney. 'Earth,' she said, putting it before her. Then she pulled the empty tin forwards to complete the square. 'Air,' she said.

She drew a triangle in the spilled flour and ash which covered the stone floor, binding the three points of fire, earth and air.

'Come,' she said in a whisper. 'Come, my Lord. I need your power.'

The bakehouse was silent. Across the courtyard in the castle kitchen a quarrel had broken out, there was the noise of a slamming door. Alys heard nothing.

She drew another triangle, inverted, binding the points for the earth, air and water.

'Come,' she said again. 'Come, my Lord, I need your powers.'

Delicately she stood, lifting her gown as carefully as a woman stepping on stones across a torrent. She stepped across the line, she broke the boundary, she stepped into the pentangle. She turned her head upwards, her head-dress slipped back and she closed her eyes. She smiled as if some power had flowed into her, from the fire, water, earth, air – from the flagstones beneath her feet, from the air which crackled and glowed around her head, from the radiating warmth of the bakehouse which was suddenly hot, exciting. 'Yes,' she said. There was nothing more.

Alys stood for a long still moment, feeling the power rise through the soles of her feet, inhaling it with every breath, feeling it tingle in her fingertips. Then she straightened her head, pulled up her hood, smiled inwardly, secretly, and stepped out of the shape drawn on the floor.

She tipped the water back in the tub. She set the tins back on their hooks and swept, with one swift, careless movement, the shape of the pentangle from the dust of the floor. She untied the purse on her girdle. Morach's candlewax moppets were cool in her hand. Alys turned them over, smiling at the accurate detail of Hugo's face, her expression hardening when she saw the doll of Catherine with its obscene slit. She went to the pile of firewood stacked at the side of the oven and pulled out a log at the bottom of the pile. She pushed in the candlewax moppets as far as they would go, and then gently put the log back in place. She stepped back and looked critically at the pile. It looked undisturbed. She picked up a handful of dust from the floor and blew it over the log so that it was as pale and dusty as the others. 'Hide yourselves,' she said softly. 'Hide yourselves, my pretty little ones, until I come for you.' Then she sat before the fire and let it warm her. It was only then, as if she were only then ready to be found, that the servant came panting across the courtyard and glanced, without much hope, into the deserted bakehouse.

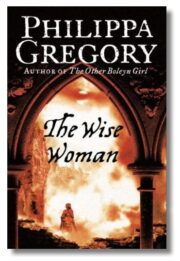

"The Wise Woman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Wise Woman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Wise Woman" друзьям в соцсетях.