He laughed carelessly, as if none of it mattered at all. 'That nonsense!' he exclaimed. 'Alys, Alys, don't cling to the old dead ways that mean nothing to anyone any more! Eat fish when you want to! Eat meat when you are hungry! Don't let me ride out all day, and chasing a wild boar too, and then turn your face away from me and tell me you won't dine with me!'

Alys could feel her hands trembling. She held the basket tighter. 'You must excuse me,' she said. 'I…'

There was a shout from behind them as someone drove a cart through the narrow gateway. Hugo pressed forward, his hands either side of Alys' head. She shrank back against the wall and then felt him, deliberately, lean his warm body against her. Her stomacher was like armour, her gable hood like a helmet. But when Hugo pressed against her she felt the heat of his body through her clothes. She smelled the clean, fresh smell of his linen, the sharp tang of his sweat. His knee pressing against her legs, the brush of his thick padded codpiece against her thigh, was as intimate as if they were naked and alone together.

'Don't you long for a taste of it, Alys?' he asked, his voice very soft in her ear. 'Don't you dream what it would taste like? All these forbidden good things? Can't I teach you, can't I teach you, Alys, to break some rules? To break some rules and taste some pleasure, now, while you are young and desirable and hot?'

And Alys, in the shadow of the doorway, with the warmth of him all around her and the whisper of his male temptation in her ear, turned her face up towards him and closed her eyes and knew her desire.

As lightly as a flicker of candleflame he brushed his lips against her open mouth, raised his head and looked down into her tranced face with his smiling dark eyes.

'I sleep alone these nights,' he said softly. 'You know my room, in the round tower, above my father's chamber. Any night you please, Alys, leave my father, climb higher up the tower instead of running to be with those silly women. Climb higher up the tower and I will give you more than a kiss in a gateway, more than a taste. More than you can dream of.' Alys opened her eyes, hazy with desire. Hugo smiled at her. His wicked, careless smile. 'Shall you come tonight?' he asked. 'Shall I light a fire and warm the wine and wait for you?' 'Yes,' she said.

He nodded as if they had struck an agreeable bargain at last; then he was gone.

That night Alys ate the wild boar when they brought it to the women's table. Hugo glanced behind him and she saw his secret smile. She knew then that she was lost. That neither the herbs nor the old lord's warning to Hugo would stop him. And that no power of will could stop her. 'What's the matter with you, Alys?' Eliza asked with rough good nature. 'You're as white as a sheet, you haven't eaten your dinner for nigh on two weeks, you're awake every morning before anyone else and all day today you've been deaf.' 'I am sick,' Alys said, her voice sharp. Bitter. Eliza laughed. 'Better cure yourself then,' she said. 'Not much of a wise woman if you can't cure yourself!'

Alys nodded. 'I shall,' she said, as if she had come to a decision at last. 'I shall cure myself.'

On that night, when Alys felt her skin burn in the moonlight and she knew the moon would be lighting the path to Hugo's room through twenty silver arrow-slits, and that he would be lying naked in his bed, waiting and yet not waiting for her, she rose and went to Lady Catherine's gallery where there was a box of new wax candles. Alys took three, wrapped them in a cloth, tied the bundle tight and sealed the string. The next morning she sent it by one of the castle carters to Morach's cottage, telling him it was a Christmas gift for the old lady. She sent no message – there was no need.

On the eve of the Christmas feast one of the kitchen wenches climbed the stone steps to the round tower to tell Alys that there was an old woman asking for her at the market gate. Alys dipped a curtsey to the old lord and asked him if she might go and meet Morach.

'Aye,' he said. He was short of breath, it was one of his bad days. He was wrapped in a thick cloak by a blazing fire and yet he could feel no warmth. 'Come back quickly,' he said.

Alys threw her black cloak around her and slipped like a shadow down the stairs. The guardroom was empty except for one half-dozing soldier. Alys walked through the great hall past half a dozen men who were sprawled on the benches, sleeping off their dinner-time ale, through the servers' lobby to the kitchen.

The fires were burning, there was the smell of roasting meat and game hung too long. The floor had been swept after the midday meal and piles of bloodstained sawdust stood in the corner, waiting to be taken out. The cooks ate well after the hall had been served, the kitchen staff had emptied the jugs of wine and dozed now in corners. Only the kitchen boy, stripped down to his shorts, monotonously turning the handle of the spit roasting the meat for supper, stared at Alys as she walked through, her skirts lifted clear of the muck.

She walked out of the kitchen door and through the kitchen garden. The neat salad beds ran along one side of the path, the herbs were planted on the other, all edged with box-hedging. At the tower which guarded the inner ward the guards let her through with a ribald comment to her back, but they did not touch her. She was well known to be under the old lord's protection. She walked across the bridge which spanned the great ditch of stagnant murky water and then across the outer ward where the little farmyard slept in the pale afternoon sunshine and a blackbird sang loudly in one of the apple trees. There were hives and pigsties, hens roaming and pecking, a dozen goats and a couple of cows, one with a weaned calf. There were sheds for storing vegetables and hay, there was a barn. There were a number of tumbledown half-ruined farm buildings. Alys knew from her work for Lord Hugh that they would never be repaired. It was too costly to run a complete farm inside the castle walls. And anyway, in these days, there was no threat to the peace of the land. Scotland's army never came this far south and the moss troopers threatened travellers on lonely roads, not secure farms, not the great Lord Hugh himself.

Alys walked through the farmyard area towards the great gate where the portcullis hung like a threat and the drawbridge spanned the dark waters of the outer moat. The gate was shut but there was a little door cut into the massive timbers. There were only two soldiers on duty, but an officer watched them from the open door of the guardroom. The country might be at peace but the young lord was never careless of the safety of the castle, and the soldiers were expected to give him value for money. One of the guards swung the door open for Alys and she bent her head and stepped out into a sudden blaze of winter sunshine. As the shadow of the castle lifted from her, Alys felt free.

Morach was waiting for her, dirtier and more stooped than ever. She looked even smaller against the might of the castle than at her own fireside.

'I brought them,' she said, without a word of greeting. 'What made you change your mind?'

Alys slipped her hand through Morach's arm and walked her away from the castle. The market stalls were set out along the main street of the town, selling fruits, vegetables, meat, fish, eggs and the great pale cheeses from the Cotherstone dairies. Half a dozen travelling pedlars had set out their stalls with fancy goods, ribbons, even pewterware for sale, and they shouted to passers-by to buy a Christmas fairing for their sweethearts, for their wives. Alys saw David walking among the produce stalls, pointing and claiming the very best of the goods and nodding to a servant behind him to pay cash. He bought very little. He preferred to order goods direct from the farms inside the manors which belonged to the castle. Those farmers could not set their own prices, and anything the lord required could be ordered as part of the lord's dues.

She drew Morach away, past the stalls and the chattering women, down the hill, and they sat on a drystone wall which marked the edge of someone's pasture and looked down the valley to the river which foamed over the rocks at the foot of the castle cliff.

'You're getting prettier,' Morach said, without approval. She patted Alys' face with one dirty hand. 'You don't suit black,' she said. 'But that hood makes you look like a woman, not a child.' Alys nodded.

'And you're clean,' Morach said. 'You look like a lady. You're plumper around the face, you look well.' She leaned back to complete her inspection. 'Your breasts are getting bigger and your face finer. New gown.'

Alys nodded again.

'Too pretty,' Morach said shrewdly. 'Too pretty to disappear, even in a navy gown and a gable hood the size of a house. Has the tisane worn off? Or is it that your looks fetch him despite it?'

'I don't know,' Alys said. 'I think he speaks to me for mere devilry. He knew I did not want him and he knows his wife watches me like a barn owl watches a mouse. He is playing with me for his sport. He takes his lust elsewhere. But the devil in him makes him play with me.'

Morach shrugged. 'There's nothing you can take to stop that,' she said. 'Lust you can sometimes divert, but not cruelty or play!' She shrugged. 'He'll take his sport where he wishes,' she concluded. 'You will have to suffer it.'

'It's not just him,' Alys said. 'That icy shrew his wife says she'll give me a dowry and have me wed. I thought it was just a warning to stay clear of her damned husband, but one of her women, Eliza, is wife to a soldier and she said that Lady Catherine has told one of the officers that she's looking for a husband for me.'

'It can't be done unless the old lord consents,' Morach said, thinking aloud.

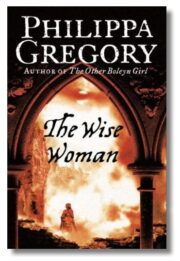

"The Wise Woman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Wise Woman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Wise Woman" друзьям в соцсетях.