Morach nodded. 'But I follow one road,' she reminded Alys. 'And they call me a wise woman rightly. This is what the Unity rune is telling you. Choose one road and follow it with loyalty.' Alys nodded. 'And the last one?'

Morach turned it around, looked at both sides and studied the two blank faces for a moment. 'Odin. Death,' she said casually and tossed the three back into the bag.

'Death!' Alys exclaimed. 'For who?'

'For me,' Morach said evenly. 'For the old Lord Hugh, for the young Lord Hugo, for you. Did you think you would live forever?'

'No…' Alys stumbled. 'But… d'you mean soon?' 'It's always too soon,' Morach replied with sudden irritation. 'You'll have your few days of passion and your choices to make before you come to it. But it's always too soon.'

Alys waited impatiently for more but Morach drank deep of the tea and would not look at her. Alys took the little purse of copper coins from her pocket and laid it in Morach's lap. Morach knocked it to the floor. 'There's no more,' she said unhelpfully.

'Then talk to me,' Alys said. For a moment her pale face trembled and she looked like a child again. 'Talk to me, Morach. I am like a prisoner in that place. Everyone except the old lord himself is my enemy.'

Morach nodded her head. 'Will you run?' she asked with slight interest. 'Run again?'

'I have the horse now,' Alys said, her voice quickening as the idea came to her. 'I have a horse and if I had money…' Morach's bare dirty foot stepped at once to cover the purse she had knocked to the floor. 'There must be an order of nuns where they would take me in,' Alys said. 'You must have heard of somewhere, Morach!'

Morach shook her head. 'I have heard of nothing except the Visitors and fines and complaints against nunneries and monasteries taken as high as the King,' she said. 'Your old abbey is stripped bare – the benches from the church, the slates from the roof, even some of the stones themselves are pulled down, and carted away for walls, or mounting blocks. First by Lord Hugo's men from the castle and now on his order by the villagers. It's the same in the north from what I hear, and the south. They'll have escaped the King's investigations in Scotland, you could try for it. But you'd be dead before you reached the border.'

Alys nodded. She held out her hand for the cup and Morach refilled it and handed it to her.

'The mood of the times is against you,' she said. 'People were sick of the wealth of the abbeys, priests, monks and nuns. They were sick of their greed. They want new landlords, or no landlords at all. You chose the wrong time to become a nun.'

'I chose the wrong time to be born,' Alys said bitterly. 'I am a woman who does not fit well with her time.'

Morach grinned darkly. 'Me too,' she said. 'And a whole multitude of others. My fault was that I gained more than I could hold. My sin was winning. So they brought the man's law and the man's power against me. The man's court, the law of men; I have hidden myself in the old power, in the old skills, in woman's power.'

She looked at Alys without sympathy. 'Your fault is that you would never bide still,' she said. 'You could have lived here with me with naught to fear except the witch-taker but you wanted Tom and his farmhouse and his fields. Then when you saw something better you fled for it.

'They thought Tom would die of grief for you, he begged me to order you home. I laughed in his face. I knew you would never come. You'd seen something better. You wanted it. I knew you'd never come back of your own free will. You'd have stayed forever, wouldn't you?'

Alys nodded. 'I loved Mother Hildebrande, the abbess,' she said. 'I was high in her favour. And she loved me as if I were her daughter. I know she did. She taught me to read and to write, she taught me Latin.

She took special pains with me and she had great plans for me. I worked in the still-room with the herbs, and I worked in the infirmary and I studied in the library. I never had to do any heavy dirty work. I was the favourite of them all, and I washed every day and slept very soft.' She glanced at Morach. 'I had it all then,' she said. 'The love of my mother, the truest, purest love there is, comfort and holiness.'

'You'll not find that again in England,' Morach said. 'Oh, the King cannot live forever, or he may cobble together some deal with the Pope. His heirs might restore the Church. But English nuns will never have you back.' They might not know I ran…' Alys started. Morach shook her head emphatically. 'They'll guess,' she said. 'You were the only one to get out of that building alive that night. The rest burned as they slept.'

Alys closed her eyes for a moment and smelled the smoke and saw the flicker of flames, orange on the white wall of her cell. Again she heard that high single scream as she ducked through the gate and kilted up her habit and ran without care for the others, without a care for the abbess who had loved her like a daughter, and who slept quiet, while the smoke weaved its grey web about her and held her fast till the flames licked her feather mattress and her linen shift and then her tired old body.

'The only one out of thirty of them,' Morach said with subterranean pride. 'The only one – the biggest coward, the fleetest of foot, the quickest turncoat.'

Alys bowed her head. 'Don't, Morach,' she said softly.

Morach smacked her lips on a sip of the chamomile tea. 'So what will you do?' she asked.

Alys looked up defiantly. 'I won't be defeated,' she said. 'I won't be driven down into being another dirty old witch on the edge of the moor. I won't be a maid-in-waiting or a clerk. I want to eat well and sleep well, and wear good cloth and ride dry-shod, and I won't be driven down into life as an ordinary woman. I won't be married off to some clod to work my life away all day and risk my life every year bearing his children. I'll get back to a nunnery, where I belong, one way or another. The old lord won't break his promise to me – he'll send me to France. If I can escape the notice of the young Lord Hugo and the malice of his wife, and if I can keep myself a virgin in that place where they think of nothing but lust – I can get back.'

Morach nodded. 'You need a deal of luck and a deal of power to accomplish that,' she said thoughtfully. 'Only one way I can think of.' She paused. Alys leaned forward. 'Tell me,' she said. 'A pact,' Morach said simply. 'A pact with the devil himself. Have him guard you against the young lord, make him turn his eyes another way. I know enough of the black arts to guide you. We could call up the dark master, he would come for you, for sure – a sacred little soul like yours. You could trade your way into comfort forever. There's your way to peace and order and safety. You become the devil's own and you are never an ordinary woman again.'

For a moment Alys hesitated as if she were tempted by the sudden rush into hell, but then she dropped her face into her hands and moaned in torment. 'I don't want to,' she cried as if she were a little girl again. 'I don't want to, Morach! I want a middle way. I want a little wealth and a little freedom! I want to be back in the nunnery with Mother Hildebrande. I am afraid of the devil! I am afraid of the witch-taker! I am afraid of the young lord and of his icy wife! I want to be somewhere safe! I am too young for these dark choices! I am not old enough to keep myself safe! I want Mother Hildebrande! I want my mother!'

She broke into a storm of crying, her face buried in her arms, leaning slightly towards Morach as if begging wordlessly for an embrace. Morach folded her arms and rested her chin on them, gazing into the fire, waiting for Alys to be still. She was quite untouched by her grief.

'There's no safety for you, or for me,' she said equably when Alys was quieter. 'We're women who do not accord with the way men want. There's no safety for our sort. Not now, not ever.'

Alys' sobs weakened against the rock of Morach's grim indifference. She fell silent, rubbing her face on her fine woollen undersleeve. A piece of wood in the fireplace snapped and burned with a yellow flame.

'Then I go back to the castle and take my chance,' Alys said, resigned. Morach nodded.

'Our Lady once chose me,' Alys said, her voice very low, speaking of a holy secret. 'She sent me a sign. Even though I have sinned most deeply, I hope and I trust that She will guide me back to Her. She will make my penance and give me my absolution. She cannot have chosen me to watch me fail.'

Morach cocked her eyebrow, interested. 'Depends on what sort of a goddess she is,' she said judicially. 'There are some that would choose you to see nothing but failure. That's the joy in it for them.'

'Oh!' Alys shrugged impatiently. 'You're a heathen and a heretic, Morach! I waste my time speaking with you.'

Morach grinned, unrepentant. 'Don't speak with me then,' she said placidly. 'Your Lady chose you. So She will keep you safe to play Her game, whatever it is. Depend upon Her then, my little holy lamb! What are you doing here, drawing the runes and praying for the future?'

Alys hunched her shoulders, clasped her hands. 'The young lord is my danger,' she said. 'He could take me from Our Lady. And then I would be lost.'

'She won't strike him blind to save you?' Morach asked sarcastically. 'She won't put out Her sacred hand to stop him feeling up your gown?'

Alys scowled at Morach. 'I have to find a way to defend myself. He would have me for his sport,' she said. 'He ordered me to his room tonight. If he rapes me I'll never get back to the nuns. He'd have me and throw me aside, and his wife would turn me out. I'd be lucky to get through the guardroom once they knew the young lord had done with me.'

Morach laughed. 'Best keep your legs crossed and your Latin sharp then,' she said. 'Pray to your Lady, and trust the old lord.' She paused. 'If you would stoop to take them, my saint, there are some herbs I know which would make you less sweet to him.'

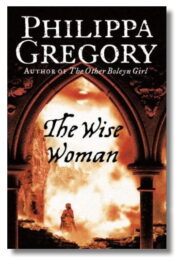

"The Wise Woman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Wise Woman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Wise Woman" друзьям в соцсетях.