If Other could see how tenderly Dreamy Gentleman valued loyalty and silence and how roughly he disdained feminine hunger and passion, she would not have made the drive to Twelve Slaves Strong as Trees. She would have known that she was not and had never been a featured player in the theater of his life. No wife would be.

But she was blind to all that. Other knew only every man she knew would give his life to be the object of her desire.

There had been someone Dreamy Gentleman loved, but not someone he could marry or that any of us could talk about. Miss Priss had a brother who worked for Mealy Mouth's Mama and Papa, and that brother was dead. They never feared Miss Priss after that; after her brother whipped up dead, Miss Priss went kind of simple. She seemed to want to make it all up to the family, the family, she said, over and over again, "what had been betrayed." Mealy Mouth's family thought she was talking about them. They continued to believe Miss Priss understood that a trusted family servant (even your brother) whispering a family secret (even in passion) was peculiar treachery. Garlic, who mourned his son, knew what his daughter meant. And knowing that Miss Priss possessed a keen and labyrinthine intelligence, Garlic seemed willing to let her balance the scales. He did very little to make amends. He just was.

But Miss Priss was there both times Mealy Mouth gave birth, the time she died, and the time she almost died. Miss Priss scares me. I don't think there's anything simple about her. So later, when they were all together during the war, when I lived at Beauty's and they were living at Other's Aunt Pattypit's, and Miss Priss told me how Other "throwed herself" at Dreamy Gentleman and how R. saw, I didn't tell her different. She thought R. was seeing her for the first time that day; she thought what Other thought. But he was only meeting her for the first time. He saw her first in his conversation with me.

It was me who told R. about Other. Even before they met, I made him see her. I didn't want to lose him, but I wanted someone who loved her to love me more than her. I made the introduction in fear with trembling. I didn't believe anybody who knew us both could love me more, but I hoped for it, and I had to know. I didn't trust Miss Priss enough to tell her how it really was then, and I don't trust her enough now, but I remember.

I fed R. from Mammy's store of how wonderful Other was-and there is something wonderful about her and it was exactly this: she has the vitality, the vigor, and the pragmatism of a slave, and into this water you stir as much refinement as you can pour without leaving any grains of sugar at the bottom of the glass. She was a slave in a white woman's body, and that's a sweet drink of cold water. In more ways than one, she thought and didn't think I was her sister. Just like in the Bible, I played Mary to her Martha, but many days it feels that it is I who have chosen the lesser part. Truth to tell, it's the lesser part what chose me. When it comes right down to it, I am Lady's child and she is Mammy's.

My mother, Lady, lost her man, Feleepe, at fifteen. When her family refused to accept him as a suitor, he ran off to some port city and was killed in a duel. Other's mother, Mammy, lived with her man all of her life, taking no public part, giving no private corner. Lady lay with Planter only the nights that were needed to bring babies. The girls who still walk this earth with me, and the boys who lay sleeping in the graveyard. Planter slept with Mammy in pleasure all their lives. In truth of body, I was the passion fruit, and Other was the bloom of civil rape. In truth of soul, Other was raised in the humidity of desire sucking boldly at Mammy's breast, and I was raised in the cool restraint of Lady's boudoir, the place to which you retreat with dignity, a place of private sorrows and private consolations, the touch of Lady's soft hand lavished on my hapless head. So Other was a child of pleasure and I a child of cold chastity, willing to be bred.

Garlic dug the grave. We had our service early in the morning, Garlic, his wife, Miss Priss, and me. Just dawn. The time of day when even servants rest. Maybe. I wanted an hour she had been at rest on earth, and I couldn't find one. Only in the lazy drag of her feet, the slow trifling ramble on any one of so many errands, did she save herself just a little from work-hard-work-long exertion, a slave's exertion.

There are two cemeteries on the place. Out back of where the cabins used to be, over a mile from the house, there is a slave cemetery. A concentration of round fieldstones (some still in stacks) and branches lashed together to create crude crosses mark for still blinking eyes the territory of the enslaved dead. It helps to squint. The ground is soft here, damp. Some suspect an underground spring. A blanket of wild grass and wild flowers covers this ground most of the year, protecting, concealing.

Closer to the house-you can see it from the porch-is the family burial ground: a rising mound of red earth beneath a tall, limb-spreading tree. In this mound are carved stones of pink Etowah marble. Pink stones, head and feet, red earth, green tree, sprigs, and odd blades of grass. Nothing much could grow in that shade. Nothing grows in this shade but names and dates and ghosts. A low wall of flat stones piled one on top of the other, a slave wall, hedges the ghost in, hedges the visitors out.

We buried her in the family plot.

Of course, Other wants Mammy buried beside Lady. What she doesn't know is a long time ago Lady's grave and Planter's were changed, looking toward just this day. Mammy be lying down beside Planter. He got himself in the middle, in death just like in life. Only the folk at the early service know that-Garlic, his wife, Miss Priss, and me.

Garlic spoke over the body. When Lady and Mammy come to the place, Garlic was there. He had chaperoned their entire journey from Savannah to the grave. He brought them to this side of the piney woods where both women got knocked up so big and quick.

Everybody suppose Garlic put it to Mammy; the master's valet follows the master and chooses the mistress's maid. Oh, peculiar economy! It was a way of making sure there was milk for the baby. Somebody plants a seed in the going to-be-wet-nurse, and then you starve that child if you have to, like they starved Miss Priss's younger brother. Garlic knew what not to say and what to say so that people would say less.

He braided what he could remember of the words from the Episcopal prayer book with his own words.

"You might could say we was the whole Trinity around this place, me, Mammy, and Miss Priss." His wife frowned, but we all knew what he meant. Garlic was right. Mrs. Garlic had bearing, height, and a kind of beauty that grew with age, but she had changed nothing of significance in any of our lives. Her stature was only apparent. Mrs. Garlic always stood in a kind of second command to Mammy, a shadow echo of a greater strength. Ultimately it was Miss Priss, so insignificant seeming so shrill, so silly, who completed the triangle that walled Cotton Farm off from the world.

Garlic was wearing the watch that I wanted for mine. I saw the golden keys hanging from it. "I was with Planter the night he won this place in a card game. Way back when.

Ain't nobody on this place know what I know 'cept Sister-that's what I came to call her-and now she gone. What I have to say I say for her.

And I say it for me, 'cause when it comes time to lay me in this ground, ain't none of ya'll be knowin' what to say.

"Planter won me in a poker game. My old master was a rich young planter from St. Simon's island. Good-looking, good-mannered, we went everywhere, Charleston, Njawlins, Washington, D.C. I been to Marse Jefferson's Monticello; you name it, I been there. I was with him when he went to Harvard. I stood in the square and got me some education while he graduated on time, not like those twins from 'round here who tumbled in and out of every college. Young Marse was something else.

So much so I couldn't be nothing. I stood in the Yard and he went to the classrooms. Yeah. Now this man heah" (tapping his toe on Planter's grave) "was a different matter. He didn't know nothing. He didn't have nothing but his white skin, spirit, and work-hard. He needed me. And I needed him, 'cause I had a vision of a place I wanted to live.

"So I mixed my young master's drinks heavy and poured my hoped-to-be-master's drink light. Wasn't good luck won Planter me. It was me poisoning Young Marse's cup. Later, Young Marse offered twice the money to get me back, and I was scared. But my new master, my soon-to-be Planter, was too proud of his first slave to let me go. I played the same trick when we won this land, but Planter was in on it. And it was me who told him when it was time for us to find a wife with a good group of house Negroes. I knew Mammy. When we first came to Savannah, Mammy told me all 'bout Lady and her troubles, and I told Planter what he need to know. I wanted Mammy for this place.

"There was no architect here. There was me and what I remembered of all the great houses on great plantations I had seen. Bremo. Rattle-and-Snap. The Hermitage. Belgrove. Tudor Place. Sabine Hall.

I built this place with my hands and I saw it in my mind before my hands built it. Mammy and me, we saved it from the Yankees not for them but for us. She knew. She knew this house stood proud and tall when we couldn't. Every column fluted was a monument to the slaves and the whips our bodies had received. Every slave being beat looked at the column and knew his beating would be remembered. I stole for this place and I got shot doing it. We, Mammy and me, kept this place together because it was ours. Here I raised my family. Right this morning we're burying the real mistress of the house." Right then I cried.

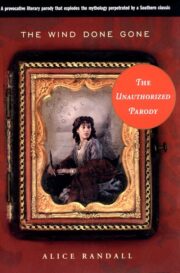

"The wind done gone" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The wind done gone". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The wind done gone" друзьям в соцсетях.