She expected me up to the end. She died sitting in a chair facing the door. She was rocking, watching the door when it opened. She croaked my name and didn't even bother to draw her last breath. She died with a look of triumph on her face and a sweet ham in her oven. She thought it was me. But it was just Miss Priss, wearing one of Other's cast-off dresses. Why she wanted to put it on, I don't know. The visiting colored preacher pronounced Mammy dead and took the ham home to his children. No one in the old house wanted to eat it.

I need to put down this pen and stop writing for me. I need to put down this pen and send a letter to R. before Other does. I want him to hear the news from me. Every time Mammy wrote to me, someone heard my news first. She had to tell somebody, and they had to write it down. I always hoped it was them that left out the words I wanted to hear.

Them and not her. I want to lay down with the body. Drape me over the mass of her.

It's a long road from where I live to Cotton Farm. And every one I have driven it with is dead. Dead, with one remaining to be buried. I want to sop up the heat from her body.

Garlic walked with me to Mammy's room at the top of the stairs. He opened the door of what I remembered to be Other's room and said, simply, "It's hua's now." For a moment I thought he meant it was hers because she had died in it, or hers because she was laid out in it. As my eyes adjusted to the vanishing afternoon light, in the gloom of closed drapes, as Garlic closed the door between us, leaving me in and him out, I saw the gingham curtains, homespun upholstery, and rag rugs.

I saw the few gewgaws and the many small labors: a quilt in the middle of being pieced together, a gown half-made, another rag rug on its way, and I knew Mammy lived in this room.

And she had died in it and would now be laid out in it. Garlic closed the door and left me alone with her body. I crawled up in the bed and got closer than she would have let me get; closer than she ever let me get. I undressed her and put her into a clean white nightgown. Her huge belly, the white hair between. I looked at her belly and wondered how I had gotten into it and how I'd gotten out of it. I wondered if I had felt strangled inside. I wondered if her love of bigness, the pleasure she took in being immense, had anything to do with a love of carrying me. I hoped that it did.

I wanted to yowl. But my mouth didn't open.

After what seemed like a long while, after it seemed I could never get up from that place, it seemed like I had to get out right then. Get out or be pulled into the grave. Like the angel of death had come and might confuse us. I arose from her bed and smoothe away my presence with my hands.

Across the room from the bed, facing the window, was a high-back chair.

She had seen the avenue of trees leading up to Cotton Farm from that window. I slumped into the chair and watched the road as Mammy had watched. Only I didn't know who I was watching for.

I was just there a little while before I could no longer bear the silence or the pain; I willed myself to doze. I don't believe I had been out for two minutes when the door opened.

Other didn't see me. The chair back hid me. I couldn't see her either. But I heard. First she sniffled and cried. Then she whined. She lay her head on Mammy's chest and told Mammy her troubles, like Mammy cared. Like she was telling her to fetch a shawl. She didn't see me at all. Not Other.

Maybe I slumped down low in the chair because I knew she would come.

Maybe I sought to hide myself so she might be revealed. Everyone at Twelve Slaves Strong as Trees knew the story of how Other threw herself and some kind of vase at Dreamy Gentleman and of how R. heard it because he was Lying down on a couch unseen. It was the one story he told me about her. And I told it to the community. Strange how on the pillow you get them to tell you-not the things you want to hear, but the things that may kill you. It was on the pillow he told me his soldiering tales.

I cleared my throat, paused a moment before rising-she could wait to see who had heard-then I rose. I stand a good three or four inches taller than she does. But her waist is smaller. Mammy used to tell me that. There are things of mine that she has taken. I could not let this hour, this visit be one of them.

She was scared, and for the first time in my life I saw her scared without her angry.

I knew if I said boo, she'd run out the room.

So I said, "Boo." Or I said, "My mother and I want to be alone, ma'am. Captain R. sends his condolences, sho do. He sent some fruit for you. Sent some for me and all the folks here too." Other ran out the room, crying.

I stepped to the door, calling softly, "Ma'am? What must I do to comfort you?"

Nowadays, Miss Priss and her mother, Garlic's family, live in the old overseer's house. The house where Lady caught some fever, smallpox or scarlet, and died. Someone has ludicrously trained rosebushes to grow up the side of this slap-dash wooden structure. Most nights Garlic sleeps in Planter's old room and leaves his bed in the overseer's house empty. He's put my bags in the trellised shack; I'm to sleep in his empty bed. Before I came down from the old house, I took a bottle from Other's dining room sideboard. I hope no one misses it tonight. I help myself to a long swig.

I walk out on the porch, hoping it will help me catch my breath.

There's no gas to illuminate the dark out here, only oil lamps and bee's-wax flame. It makes for a different color of night. The stars are brighter. It's hard to see to write.

There are so many things of Other's I have wanted. Things, then people. People more than things-but nothing she has ever had, no emerald, not R." have I ever wanted as much as I wanted her love for Mammy. As the sun sets, it don't hurt near as much that Mammy didn't love me as it hurts that I didn't love Mammy.

Once upon a time I loved my mother. But that love was frail and untended; I let that love die. No, it wasn't like that, like a plant in a pot deprived of water. Truth is that love got some sort of sickness that moved so quick and there was no doctor to tend the patient and my love just died. I had no idea in the world how to stop that death from coming once it started, and started coming on quick. It was like the smallpox moving through the house, leaving scars and death, and you're scared to see it coming. And you never forget it came. Just like the first time you see a dead body, you know one day death's coming for you too. The first time you stop loving somebody, you learn all love ends. And loving somebody is just the graceful practice of patience before the love dies.

I know exactly where my love for Mammy is buried. Like an unembalmed beast left decaying in the yard of my mind, it stinks the place right up to high heaven. Is there a low heaven? Can I drift there and stay close to her?

It hurts not to love her. And it hurt more when I didn't -I still don't-believe she ever loved me. I close my eyes after writing that, after making that witness, and I wince in a breath. God damn her soul!

And it's less a curse than a fear. What do God do with folk who won't see the beauty He put in all creation? What do He do when He tired of hearing the angels weeping? I know the angels weep every time a dusky Mama is blind to the beauty of her darky child, her ebony jewel, and hungers only for the rosebud mouth to cling to the plum moon of her breast.

Don't I understand why Miss Priss killed Mealy Mouth? Don't I remember Garlic's wife with Mealy Mouth and Dreamy Gentleman's Harvard-going brat at her breast? Miss Priss lost two brothers to that woman. It's all so mixed up. I take a sip more-or is it more than a sip-from Other's brandy bottle, and my memories are like fish in a bowl swimming one way and then another, detached, insignificant, but still I turn back to look, remember, watch, mesmerized as the memories glide past.

R. didn't have too many bedroom memories of Other to tell, to hold back. But sometime during the afternoon that Georgia entered the war, he felt her breath on his face, and that breath left its imprint on his eye. Other never knew, didn't guess, I was the one first spoke her name to him. To get her out of my head, I put her in his. That's not what I intended to do, but I did something, and that's what happened. I was the one told him 'bout her.

I'm trying to remember about that time and get it straight. R. had gone to the picnic barbecue at Twelve Slaves Strong as Trees, gone to do a little business, he told me. I believe now he went there to see her. Other had gone in the hopes of getting Dreamy Gentleman to ask for her hand in marriage. But that was not to be, and everybody but Other had seen it a long time coming.

Dreamy Gentleman had made up his mind to marry his cousin Mealy Mouth, a flat-chested slip of a girl who would never ask more from marriage than family. She didn't have the first idea about passion between a man and a woman, but she possessed a fiery loyalty to family, particularly to her brothers, that attracted Dreamy Gentleman profoundly. He saw luscious possibilities in that loyalty. And he saw a fine line of children springing from his loins (which he coveted and hoped he deserved), golden children that would resemble his beautiful cousin, resemble all his cousins, for they greatly resembled each other.

Dreamy Gentleman was a particular friend of Mealy Mouth's brother (not the young one Other would marry; an older brother nobody really talked about). This brother played Cupid for Mealy Mouth and Dreamy Gentleman; Dreamy Gentleman could not but be slain by Mealy Mouth's brother's golden arrow. Mealy Mouth was grateful to her brother for forming the attachment.

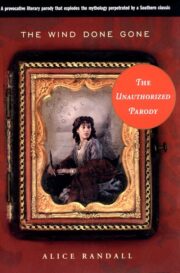

"The wind done gone" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The wind done gone". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The wind done gone" друзьям в соцсетях.