"Madam, when I first met you I was impressed by your deportment." (I would rather he had said intelligence and simple grace.) "You were in a difficult position, but you handled yourself with modesty. (I would rather he had modified the modesty perhaps by adding simplicity, humble modesty.) "All eyes could see that you were in the best and the worst sense of the word married. But you bore the yoke with..." (Did he call it grace?) "When you married, we were happy for you. Every Negro man who had a mother forced or cajoled by the master raised a cup to your victory. But now you come to town with no husband, only an intent on sullying the good name of one of the great dark men in the Capital City. I can't but join my fellow citizens in disapproving.”

“I don't think you know anything of my situation.”

“I can smell him on you." It was the most vulgar sentence I had ever had spat at me. I know what he meant. I had washed the linen at Beauty's. Being a doctor is another kind of washing of the bedsheets.

"He will never be elected again if he keeps up with you. Voting Negroes won't vote for a man living with another man's wife." I tried to interrupt him, but he wouldn't be stopped. "Whoever you think you are, in the polite society of Negro teachers and preachers and lawyers and doctors, you will always be the Confederate's concubine." He was on a roll. "You have a greater chance of being accepted among old white families than new colored ones." And he kept on going. "We're a prim and proper lot."

I hadn't thought of this. I hadn't thought of very much at all. My business in Washington is complete. I should return by the first train to Atlanta. It would be the sensible thing to do, and I am a sensible woman. No lady in any novel I know makes the kind of mistakes in books that I make in life. In all the literature I know, only one book comes close to what I feel. This is Great Expectations. Pip has a guilty family. Almost guiltier than mine. What is owed the rescuer? Do we always fall in love with those who rescue us? Didn't I know Miss Havisham in calico? What don't Estella and Other have in common? How easily Pip accepted his good fortune. I envy white boys that most of all-their certainty that they're going to be or get lucky. It occurs to them to live with great expectations. It occurs to them to do what they want and not worry about it. It occurs to R. to do that all the time. It doesn't occur to me at all. It occurs to me to run back to Atlanta.

R. has moved back into Other's house. Her children are there, and they need him. There's the grand staircase he once carried her up-and too many rooms to count.

This is where we huddled together when Precious died.

He sends a card 'round to my house, and I arrive at the appointed hour for my visit. We make love. He traces the butterfly on my cheek. And he asks if I am going to be all right. I tell him yes-and I tell him that I'm leaving him in the morning. In the morning, I'm leaving him.

I've just made up my mind to do it. When I said it, I was letting him know how unhappy I am. Now I'm hearing myself. I'm leaving in the morning.

"I gave you my name," R. says.

"I never told you mine," I reply.

Mammy never rode the train. I've got Lady's emerald ear bobs in my purse. I took them from Other's jewelry box. Some folks say emeralds are higher than peridots because there are more peridots in the world. It's what's scarce is high. Some folks say it's because emerald got a prettier color. I say it's because the rich folks found emeralds first and have more of them, so they say the peridot be just a little better than green-colored glass to give higher value to what they have a higher number of. Like white blood. But a man made the green-colored glass and God made the emerald and the peridot, and I can't help knowing the peridot is the pretty color of grass in the fall, the color of living things that survive the thirst of late summer when there's so much gold in the green. I see the peridot and the emerald are the same beautiful thing, and green glass is something altogether different.

I'm riding on the train up to Washington, alone. I don't send word ahead. No. All I have taken out of his house are her things. I take her things and leave her-him. This is the best I can do with this algebra of our existence. She gets him, and I get her things.

Everything he bought me I left behind, every pair of bloomers, every barrette, the peridot ear bobs the wedding ring, everything. I cannot go to my Congressman in R.’s things.

I went up to her room. I opened the closet: a sea of green, velvet, satin, silk; a gown or two in black; a blue day costume; hats. It was said around Atlanta that she liked green best because it is the color of money. But I who knew her from the first day either of us knew anything, knew that she loved green before she even knew what money was.

You don't see paper money on a cotton farm. You don't even see paper money on what it was and I have not wished to claim, a great Georgia plantation. On a place like that, in the place we lived together, half-sisters separated by a river of notions: notions of Negroes and notions of chilvary, notions of race and place, notions of custom and rage; in the country we inhabited in our childhood, you measured wealth in red earth and black men. There was nothing green in it.

Green were the leaves, green was the grass, green the grasshoppers, green all the insignificant pretty things, all the moving tokens of living, and that's why Other loved green, because she was, or saw herself to be, an insignificant pretty living thing. She didn't wear it because of the money or because it matched her eyes. She wasn't, in fact, vain. She knew I was the prettier one. Knew it right off and didn't let it worry her.

She wasn't pretty, but she had the capacity to distract men from noticing that. And now that my looks are vanishing with the years, I must borrow that from my sister; I must learn to make men not notice that I am not beautiful. Her dresses are a fine beginning. I will go to my Congressman in my sister's clothes.

I packed in her trunks. I look at my reflection in the window and it's a blurry thing, but I see me as I have never been before. I wear green well. For somehow, too, green is Daddy's Ireland.

Garlic told me the story. He got it from Mammy, who had got it from Planter. Planter ran out of Ireland with the law on his tail, wanted for a murder he had committed. And thieving he had thieved. He couldn't see other people have everything when his family had nothing.

And when things were too hot in that country, he quit it. That was her father and that was mine.

She was like him in that she killed. Miss Priss told me that story.

She, Other, and Mealy Mouth killed the Union soldier, robbed his dead body, and dragged him off in their chemises, all the while making light conversation with the family out the window. I come from a strong people. And I am like him in my willingness to leave my world to find a better one. It is a sister and a family I leave behind, not Other, not some thing.

Once in Georgia I had a sister who loved my mother dearly; she took care of Mama all her life, better care of her than I took. I hated her and buried her, and now I forgive her. Once in Georgia I had a mother I could not find my way to loving. I'm grateful that Other found a way and kept the path clean and brightly used. She made exquisite use of my mother's love.

And now it's my turn to make good use of her mother's love. Lady loved her black man in the bright light of day. If he will have me, I will love Adam, I will love my Congressman that way.

R. writes me letters it would bore me to return. He is someone else's dream. Whose dream I'm not sure. I suppose Beauty's. Beauty stretched the scope of her imagination to see him, to want him. She didn't like men, but she loved him. That's tribute. Other loved him when she had nothing else to love. It was a scrawny little pathetic love, and he wouldn't have it. And me, I loved him because he was the prize, and I wanted the prize to feel and know, taste and see that I could win it, but it was his power I craved, not him.

I tell him, I have been sleeping in my sister's bed. I don't want that anymore.

He tells me, I saw you before I ever saw her, wanted you before her.

But then you chose her because you could and she reminded you of me.

She was your daylight version of me. You betrayed me and I betrayed her on so many succulent occasions, too many succulent occasions. But I no longer have a taste for that meat. It's too rich for me. I want something simple, like a cold joint of ham, a slice of cornbread, and a big glass of buttermilk. I want to love a stranger who knows no one I know. You have been a father to me, and now that you look the part, I don't want you. His eyes well up. I won't give you a divorce. I'll live in sin. Proudly. You taught me that.

"What is your name," he asks me.

"Cynara," I say, walking out his door.

(am traveling unescorted. I feel nauseous. There are rascals of every hue on this train. Whatever remained of my good name will be gone by the time we reach Washington. Why doesn't anyone assume that a woman on her own wants to be?

The Congressman doesn't know I'm coming. The election is fast upon him; he doesn't need anything more to worry him. He can't imagine I will come.

R. imagined I would go. He sent a note 'round to my house. I call it my house because he gave it to me, because my name is on the deed, and because, as Beauty says and it's ugly to admit, I earned it.

R. wrote to say that if I was going to Washington, I could stay at "the house." He doesn't say my house, and he doesn't say ours. His kindness makes me cry. I am touched that he knew, could figure out, what I would do; his kindness makes me cry, but I can't accept it anymore.

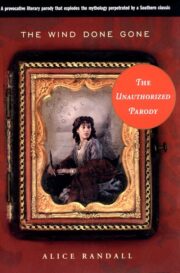

"The wind done gone" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The wind done gone". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The wind done gone" друзьям в соцсетях.